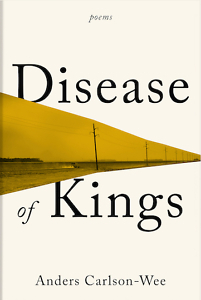

How to Live and at What Cost

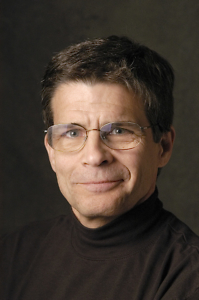

Poet Anders Carlson-Wee on his new collection, Disease of Kings

Publishers Weekly described Anders Carlson-Wee’s first collection, 2019’s The Low Passions, as “restless and searching, taking readers through the truck cabs, living rooms, dumpsters, freight yards, and railways of America’s wide middle.” Something similar might be said of his second book, Disease of Kings, but the searching here is more spiritual than physical, the restlessness more intimate than expansive.

In the narrative that drives much of the collection, the speaker and his friend North scrabble to live off the fat of the land, which in the 21st century U.S. means taking advantage of the endless waste of a consumer economy. They dumpster dive for food and raise cash by holding fake moving sales with items they’ve scavenged. Other characters — odd, sad, sometimes generous — pop up in the poems, their fleeting presence a kind of counterpoint to the deep relationship with North. The speaker, ultimately left on his own, remains adrift in solitude he can neither give up nor settle into comfortably: “The longer I’m alone / the smaller a gesture could be // and still console / or rattle me. Strange to need // so little, but to need it / so badly.”

Carlson-Wee, a Minnesota native who earned an M.F.A. in creative writing from Vanderbilt University, lives in Los Angeles. He answered questions about Disease of Kings by email.

Chapter 16: Many of these poems are built around a scene, a particular incident or encounter, and in that sense they’re narrative. Do you think of yourself as a storytelling poet?

Anders Carlson-Wee: Absolutely, I’m a narrative poet. That’s how my brain works: through stories, quarrels, courses of dramatic action. I don’t really know how to think another way. When I started working on Disease of Kings, I found myself drafting poems about friendship — specifically the friendship between the book’s speaker (who’s based on me) and North, his only friend. In contrast, I also found myself writing poems about extreme loneliness. Following these two impulses, I slowly cobbled together the story of this odd couple, with their hyper-specific lifestyle of dumpster diving for everything they need: food, clothes, shoes, painkillers, etc. Disease of Kings is based on my life in my 20s, a time during which I stopped buying food altogether and lived solely on what I could find in the trash. This extreme stinginess allowed me to work minimally (as a personal trainer at the YMCA) and devote the majority of my time to reading and writing. So my pathological frugality is at the core of Disease of Kings, and it’s also what afforded me the time I needed to write the book.

Chapter 16: Gratitude for the kindness of strangers is a theme that arises repeatedly in this collection. It’s easy to wax sentimental about kindness, but that’s not what you’re about in these poems. What draws you to those moments of fleeting kindness?

Carlson-Wee: In my 20s I traveled extensively — bicycled across the country twice; hopped freight trains through the South, Midwest, and up and down the West Coast; hitchhiked to the Yukon and back; and walked on foot across Croatia and Bosnia over the Dinaric Alps. During these travels, I slept outside every night, unless a stranger took me into their home — a radical act of kindness that I found to be shockingly common, especially if you’ve heard the vitriol on the news about how cruel the humans of this world are supposed to be. Contradicting all that doom and gloom in the media, I found that people from every walk of life, and from a range of remote cultural corners, tend toward — not hatred and fear — but generosity. As a poet, I’ve felt drawn to dramatize those beautiful experiences.

Chapter 16: There are some indelible images scattered through the collection, as well as countless sensory details. You’re pulling readers into a richly physical world. Your aesthetic could be read as a reaction to our increasingly disembodied, digital existence. Do you see it that way?

Carlson-Wee: I’m extremely driven by sensory experience. I grew up rollerblading and did that professionally in my teen years. Rollerblading made me acutely aware of my body — the nuances of breath, balance, momentum, flexibility, temperature, etc. I began writing seriously at Fairhaven College, where I designed my own degree entitled “Writing through the Body,” which focused on how the body fuels the mind’s creativity. So the richness of the physical world is at the forefront of not only my writing, but also my imagination: It’s where I’m coming from, each time I put pen to paper. On top of all that, as a dumpster diver, the five senses are crucial for deciding what’s safe to eat — especially the sense of smell. I only hope my 20 years of dumpster discernment have enhanced the sensory qualities of my poems.

Carlson-Wee: I’m extremely driven by sensory experience. I grew up rollerblading and did that professionally in my teen years. Rollerblading made me acutely aware of my body — the nuances of breath, balance, momentum, flexibility, temperature, etc. I began writing seriously at Fairhaven College, where I designed my own degree entitled “Writing through the Body,” which focused on how the body fuels the mind’s creativity. So the richness of the physical world is at the forefront of not only my writing, but also my imagination: It’s where I’m coming from, each time I put pen to paper. On top of all that, as a dumpster diver, the five senses are crucial for deciding what’s safe to eat — especially the sense of smell. I only hope my 20 years of dumpster discernment have enhanced the sensory qualities of my poems.

Chapter 16: The relationship between the speaker and North seems both loving and distant, as if nothing can quite puncture the speaker’s sense of isolation. He seems existentially lonely. How do you see his condition?

Carlson-Wee: Yes, the speaker in Disease of Kings is profoundly lonely, and although his friendship with North curbs the worst of it, his lonesomeness haunts him at all times and in all places. He’s a troubled person — timid, self-conscious, miserly, and terribly stubborn. Yet his redemptive qualities are his loyalty and abidance: He wants to keep and maintain the world he’s built and wants nothing to be lost or wasted — including his friendship with North. He fears newness, and over the course of the book, as the world changes all around him, he’s unable to change with it. Ultimately, North moves on from their shared life, while the speaker remains — lonelier than ever, but also grateful for what he has.

Chapter 16: The speaker lives on the margins, but there seems to be an element of choice involved. He’s smart and resourceful and perhaps could live a different way. Does his choice complicate his perspective? Is he really speaking from the margins?

Carlson-Wee: He’s speaking from where he is and from who he is. He’s the son of two Lutheran pastors who love him and can bail him out anytime he gets into trouble; this is a source of shame and embarrassment throughout the book. In stark contrast, his friend North not only has no safety net, but is actively taking care of (and paying for) his alcoholic father. These unbridgeable differences create tension throughout the collection and ultimately come to a head in the poem “Good Money,” in which North takes a full-time job fishing in Alaska, an act of responsibility that wrenches the two of them apart. These questions of choice and responsibility, of how to live and at what cost, are at the heart of Disease of Kings. I hope readers quarrel with these questions and find them engaging.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.