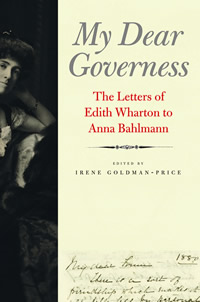

“I Shall Never Have a Friend Like Her”

With a superbly edited collection of letters, Irene Goldman-Price offers fresh insight into the life of novelist Edith Wharton

In 1873, Edith Wharton—then Edith Jones and known to her family as Pussy—was eleven years old, and, like many girls of her social class, she received her schooling at home. That year her parents hired a governess named Anna Bahlmann, and teacher and pupil soon developed a close bond. After Wharton outgrew the need for a governess, Bahlmann became her secretary and companion, and their relationship lasted until Bahlmann’s death in 1916. In My Dear Governess: The Letters of Edith Wharton to Anna Bahlmann, Irene Goldman-Price traces the disparate but intertwined lives of the two women. The letters, along with Goldman-Price’s superb annotations, give an account of Wharton’s early years that is at odds with her published recollections. In her portrait of Anna Bahlmann, Goldman-Price also delivers a glimpse into the life of an unmarried, educated woman struggling to earn a living during Wharton’s day.

In later years, Wharton—by then an acclaimed novelist—expressed some regret about the education she received. In her memoir, A Backward Glance, she noted that she was taught only “the modern languages and good manners” and “a reverence for the English language.” Within the limited scope of that curriculum, however, Bahlmann was an excellent teacher. Goldman-Price describes her as an “erudite, refined person in her own right,” with knowledge of art and architecture as well as languages, and a genuine love for children. Bahlmann, in turn, found a remarkable pupil in Wharton. In a letter written to Bahlmann on November 13, 1875, Wharton offered her opinion of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “His poetry always reminds me of a chilly sculpture, it is so lifeless,” she wrote. “I think his characters want vigour.” She went on, however, to praise specific lines, and volunteered that she likes “occasionally to have a discussion about poetry.” Even taking into account Wharton’s desire to please her beloved teacher, the letter’s tone and content are impressive, revealing a literary intelligence that is already burning brightly.

In subsequent letters, Wharton sent her own poems to Bahlmann and thanked Bahlmann for her “kind criticism.” This evidence of active support for Wharton’s early efforts runs counter Wharton’s own descriptions of the period, in which she depicted herself as a creative child unhappily surrounded by adults who took little interest in her writing or her intellectual development—in Goldman-Price’s phrase, “a literary orphan.” The letters reveal lively family involvement and concern as well. “The romantic notion,” writes Goldman-Price, “that Edith Wharton was a solitary autodidact is one of her most successful fictions.”

In subsequent letters, Wharton sent her own poems to Bahlmann and thanked Bahlmann for her “kind criticism.” This evidence of active support for Wharton’s early efforts runs counter Wharton’s own descriptions of the period, in which she depicted herself as a creative child unhappily surrounded by adults who took little interest in her writing or her intellectual development—in Goldman-Price’s phrase, “a literary orphan.” The letters reveal lively family involvement and concern as well. “The romantic notion,” writes Goldman-Price, “that Edith Wharton was a solitary autodidact is one of her most successful fictions.”

Bahlmann’s role in Wharton’s adult life evolved according to Wharton’s needs. Although she continued to take jobs as a governess, Bahlmann always maintained an attachment to her most gifted student. She served as a personal secretary at times, and she was also a companion to Wharton’s mother. She helped Wharton manage her husband, Teddy, who was mentally unstable. The letters during these years are rich in practical and family concerns but largely free of intellectual or literary subjects. The letters also give no hint of Wharton’s notorious affair with Morton Fullerton, though Bahlmann knew and liked him. The chief value of the later letters is what they reveal about Bahlmann’s critical role in supporting Wharton’s ambitions. “Certainly Anna Bahlmann’s work enabled Edith Wharton to do her own,” Goldman-Price writes, noting that Bahlmann’s help was essential in freeing the writer from family obligations that would have interfered with her work and the literary friendships she treasured.

As for Bahlmann’s own ambitions, they are impossible to know, although Goldman-Price quotes her as telling one of Wharton’s friends that she lived primarily to serve her former pupil: “For years the only object I have had in life has been to help Edith and spare her trouble and fatigue.” It’s a poignant statement coming from a woman who was highly intelligent and, by all accounts, lively and charming.

As for Bahlmann’s own ambitions, they are impossible to know, although Goldman-Price quotes her as telling one of Wharton’s friends that she lived primarily to serve her former pupil: “For years the only object I have had in life has been to help Edith and spare her trouble and fatigue.” It’s a poignant statement coming from a woman who was highly intelligent and, by all accounts, lively and charming.

In spite of the limited information available about Bahlmann, Goldman-Price offers a moving portrait of her existence on the fringes of wealth and society. Bahlmann struggled financially, in part because she was sometimes reluctant to accept Wharton’s generosity. While Wharton was genuinely fond of her, she did not regard Bahlmann as a peer or a true part of the family. “Anna was part of her household, a member of what Edith referred to as ‘the gang,’” writes Goldman-Price. Bahlmann shared that designation with the housekeeper and the cosseted dogs. (Perhaps this is the place to note why the book contains almost nothing from Bahlmann herself: while Bahlmann’s heirs carefully preserved Wharton’s letters, Wharton and her family apparently saw no reason to save Bahlmann’s.)

Just after Bahlmann’s death, Wharton wrote Bahlmann’s niece and declared, “I shall never have a friend like her, so devoted, so unselfish, so upright, so sensitive & fine in every thought and feeling.” To a friend, Wharton described herself as “completely crushed by this last blow.” Even so, beyond a few brief mentions in her memoir, Wharton never publicly acknowledged all she owed to Bahlmann. With My Dear Governess, Irene Goldman-Price has not only added valuable material and insight on Wharton, but she has also, at least in some measure, given Bahlmann her due, covering a debt Wharton left unpaid.

Irene Goldman-Price will join novelist Jennie Fields, author of The Age of Desire, for “A Talk on Edith Wharton” on September 20 at 6:15 p.m. at the Nashville Public Library, as part of the Salon@615 series. The event is free and open to the public.