I Was a Teenage Voyeur

On my journey from Nashville to Greenwich Village

My Nashville adolescence was a time adrift without any clear idea of who or what I wanted to be. The people around me in public high school all seemed like people I wouldn’t want to become, and they seemed to view me in the same light. I worried a lot about what kind of life I should aspire to. Most of the rest of the time I thought about whether I would ever make physical contact with a girl, and if so, what it would be like.

These two obsessions came together in odd fashions. Not so odd perhaps, were the evenings I spent in the shadows under a tree outside the bedroom window of a classmate who lived down the street, hoping to see her get up from the desk where she studied each night, and undress, take off her clothes and put on pajamas. I was keenly alert waiting for that moment just before the pajamas. Every night I imagined over and over what she would look like naked. It never happened. I could never stay late enough to see her get ready for bed. Okay, that behavior was not so odd, now that I think about it. There were probably a good number of nighttime voyeurs among my male mid-adolescent cohort. It was probably nothing out of the ordinary in the 1960s.

What was a little odder was my behavior as a daytime voyeur. I was in the habit of spending the afternoon hours after high school let out by walking around and following someone at random, with no more motive than to see what they did, where they went, who they were. I didn’t do it pretending anything, I wasn’t imagining myself as a spy or a robber or a private detective, or anything else. I picked out someone and went about following them for an hour or two, until it was getting dark and time to head home for supper. Observing them. Trying to feel their lives and assess the possibilities. Not your usual high school extracurricular activity.

Everything began to clear up during my 15th summer with a trip to Long Island from Nashville for a week’s visit with my father’s brother’s family, my first time on the East Coast. I still had not had an opportunity to begin solving the puzzle of a woman’s body, but that summer I finally did find a role model for adulthood, a life that I could aspire to. The visit opened up new vistas to me, a panorama of possibilities taken for granted by people living in the Long Island suburbs that I had never considered. Things like Chinese food: I began to realize that my mother’s cooking was not how the rest of the world ate. Who could ever have imagined these dishes, chop suey and lo mein? And pizza: It was nothing to my cousins to walk down to the local strip mall with its pizza joint and get a slice each, a big wedge for a buck, delicious and wholly new to me.

We went to Jones Beach on the weekends and actually swam in the ocean, and to Coney Island where we rode the Cyclone, one of the world’s outstanding roller coasters. Nothing I had known came close to the thrill of sitting in the lead car of the Cyclone, right up front, as it climbed ever so slowly up the track to the summit from which it descended at a tremendous rate of speed, everything unfolding at tremendous velocity right in front of my eyes when I could keep from closing them in terror. I rode it again and again. All these things so far away from the Nashville life I knew were enough to confirm my suspicion that a much wider world existed than I had encountered.

One Saturday night it was decided by my uncle and aunt that we would “drive into the city” and splurge for an Italian dinner at Minetta, a tavern in Greenwich Village, open since 1937, and once a hangout for a mid-1950s literary set. My dad and his brother both wore sport coats and ties for their visit to Manhattan. We rode around Greenwich Village looking for a parking spot. My uncle grew increasingly nervous and irritated behind the wheel, because we could lose the reservation if we weren’t there on time. I would have kept circling the streets all night, looking out the station wagon’s back window, enthralled.

It was a warm, summer Saturday evening in the Village. People were sitting on the steps of their buildings, relaxed, laughing with their friends. A guitarist strumming quietly, a transistor radio on a step with a baseball game being announced. Men and women with their arms around each other, lounging, laughing. People sitting on the stoops doing nothing more than smoking a cigarette or sipping from a can of something. No one wearing a sport coat or a tie. I was thrilled to see that people lived like this, enjoyed each other, relaxed into the world around them as it passed by. “Beatniks,” my uncle told the car-at-large, contempt in his voice, waving a hand at a row of front stoops and their occupants. “That’s what they call them.”

What I called them was what-I-wanted-to-be-when-I grew-up. My days of following strangers were done.

Copyright © 2025 by Richard Schweid. All rights reserved.

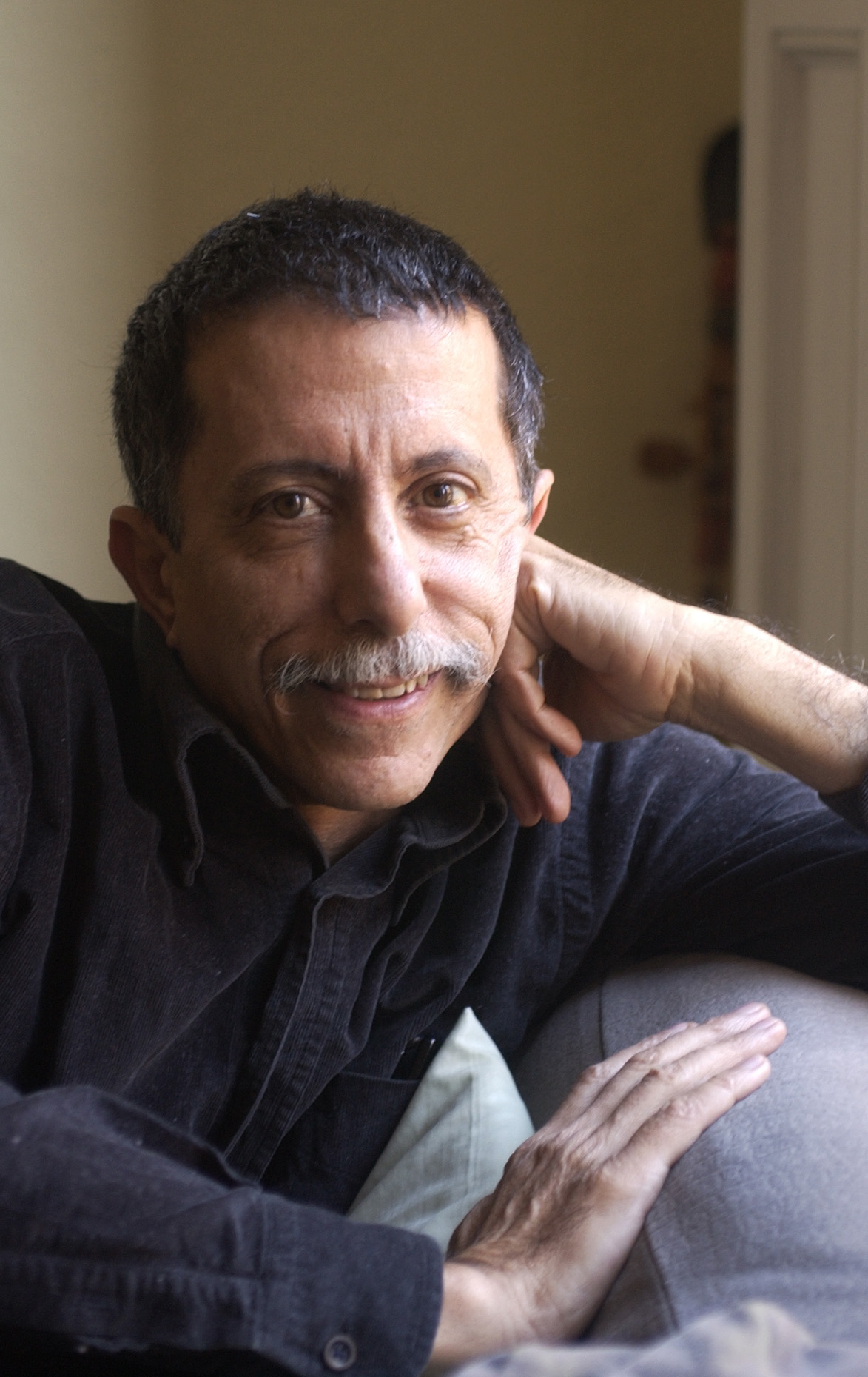

Richard Schweid is a Nashville native and the author of more than a dozen books, including Octopus, Invisible Nation, and The Caring Class. Life on the Octopus Farm: The Ethics and Future of Growing the World’s Most Intelligent Invertebrate is due in 2026 from the University of North Carolina Press. He lives in Barcelona, Spain.