Icons and Brothers

Johnny Smith talks about the fractured friendship of Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X

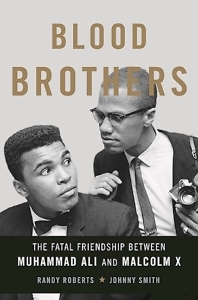

In Blood Brothers, historians Johnny Smith and Randy Roberts chronicle the friendship of two dynamic figures: Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. Combining meticulous research with intense writing, they reveal the importance of Malcolm X in constructing the persona of Muhammad Ali. At the same time, they explain the centrality of Ali in the history of the Nation of Islam. Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X inspired both affection and fear from the American public, even as their friendship was cracking.

Johnny Smith is an assistant professor of history and an award-winning teacher at Georgia Tech. His writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New Republic, Slate, Salon, and The Daily Beast. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Johnny Smith is an assistant professor of history and an award-winning teacher at Georgia Tech. His writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New Republic, Slate, Salon, and The Daily Beast. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Today, both Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X seem enshrouded in myth, somewhat tamed and commodified. And in their own heyday, each was a man of masks, capable of playing a character to project an important message. Is it possible to penetrate past these images, to see them as flesh-and-blood individuals?

Johnny Smith: One of the main reasons Randy Roberts and I wrote Blood Brothers was because over time Muhammad Ali’s image became distorted. Over the past few decades, politicians, writers, television producers, filmmakers, and his corporate sponsors reconstructed an image of him as a unifying force of goodwill. But in the 1960s, Ali divided the country. His relationship with Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam made him one of the most despised black men in the country.

Collecting primary sources—FBI files, State Department records, Malcolm’s personal papers, the daily press, interview transcripts, and a variety of published and unpublished materials—allowed us to peel back the layers of each icon. Investigating their relationship reveals how Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali. We tried to recreate their public and private worlds. As public figures, Ali and Malcolm performed acts of heroism by challenging white supremacy. But they also made questionable choices that remind us that the images of our heroes are often incongruent with reality.

Chapter 16: Your book reveals a young Cassius Clay’s fascination with the Nation of Islam. What was its appeal to him?

Smith: Cassius Clay’s interest in the Nation of Islam stemmed from his experiences as a young boy growing up in segregated Louisville, Kentucky. His father repeatedly warned him to avoid white men, or he would end up like Emmett Till. He was nearly the same age as Emmett, and the grisly pictures of Till’s mutilated body horrified young Cassius. So when he first began hearing the Nation of Islam’s ministers preach that white men were evil and that blacks must separate from them, it made sense to him. A Black Nationalist philosophy offered Cassius a sanctuary from the violent world of white supremacy. Furthermore, Elijah Muhammad preached a message that he would begin repeating throughout his boxing career: the black man was the greatest.

Chapter 16: What did Malcolm X see in Cassius Clay?

Smith: When they first met in June 1962, Malcolm had no idea who Clay was. But gradually, as Clay began attending more NOI meetings, Malcolm recognized that there was something special about the young boxer. Like Malcolm, he was self-assured, proud, and defiant. Cassius boldly professed his own greatness the same way that Malcolm fearlessly denounced white men. As their relationship grew, Malcolm noticed how Cassius could attract a crowd and manipulate reporters into spreading his message. It made Malcolm consider Clay’s power: what if a black heavyweight champion used boxing as a platform for disseminating Black Nationalism? But a feud developed between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad that forced Cassius Clay to decide which leader he would follow. Once Clay won the heavyweight title in February 1964, he became a pawn in their power struggle.

Chapter 16: What was the nature of their friendship? How did it evolve?

Smith: Their friendship really matured throughout 1963 and into early 1964. Clay fought only three times in 1963, so he had more free time to attend the Nation’s rallies and visit Malcolm’s mosque in Harlem. But their relationship remained clandestine until January 1964, when Malcolm visited Clay’s training camp in Miami. Up until then, the press suspected that Clay was involved with the Nation, but he evaded questions about his connection to Malcolm. If he revealed his ties to the Nation—a sect most Americans deemed a hate cult—he might ruin his boxing career. But during interviews he imitated Malcolm, echoing his Black Nationalist rhetoric. He saw Malcolm as an older brother, a mentor who filled him with greater confidence. Malcolm convinced Cassius Clay that through boxing, he could become a champion of Black Power.

Chapter 16: In your research for Blood Brothers, you constructed a day-by-day timeline of each man’s activities. How did this exercise shape your story?

Smith: The timeline helped us place the two men together at previously unknown moments. It also helped us search for more newspaper coverage. Following this trail, we were able to show what Clay witnessed inside the Nation’s meetings and the messages he absorbed. This timeline was critical to reading and interpreting FBI files, which were redacted in many cases. Without knowing the context of the quarrels inside the Nation, we wouldn’t have been able to decipher the meaning of conversations and events recorded in those FBI files.

Smith: The timeline helped us place the two men together at previously unknown moments. It also helped us search for more newspaper coverage. Following this trail, we were able to show what Clay witnessed inside the Nation’s meetings and the messages he absorbed. This timeline was critical to reading and interpreting FBI files, which were redacted in many cases. Without knowing the context of the quarrels inside the Nation, we wouldn’t have been able to decipher the meaning of conversations and events recorded in those FBI files.

Chapter 16: The 1960s witnessed new forms of journalism, the surging role of television, and a vibrant consumer-oriented youth culture. How did these modern trends shape the impact of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali?

Smith: Both men thrived beneath the spotlight. Neither man could resist a platform, interview, or debate. They enjoyed sparring with words and using the kind of sensational language that made headlines and sound bites. This made them ideal television actors. In many ways, their political and cultural influence was shaped by the growth of television. Both men used it to reach their audience: Malcolm appealed to young disaffected black Americans, while Ali promoted his fights—and himself. Although Malcolm remained on the periphery of the mainstream civil-rights movement, he used television interviews as a way to insert himself into the center of national political debates. Similarly, Ali understood that every fight needed a villain, and he gladly performed this role. When we look back on their relationship, though, we should not forget that their brotherhood challenged journalists to ask new questions about the relationship between race, sports, and politics—questions that the media continue to ask today.

Chapter 16: Both men are global icons, their faces and names known throughout the world. Why have Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X resonated with so many people around the world?

Smith: Throughout their lives Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X were globetrotters, traveling to distant corners of the world, advocating black freedom at home and abroad. Ali fought fifteen times outside of the United States—nearly a quarter of his professional bouts. In the satellite era, his boxing matches became global spectacles that attracted record viewing audiences. Those fights made him one of the most visible figures in the world. Perhaps more important, during the Vietnam War he voiced opposition against racism and anti-colonialism. Like Malcolm before him, he became an outspoken critic of U.S. foreign policy. And both men embraced orthodox Islam, a religion practiced far more outside of the United States. Ultimately, Ali and Malcolm endure as global icons because we remember them as freedom fighters.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.