“I'd Rather Be There than Any Place I Know”

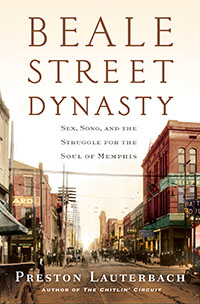

In Beale Street Dynasty, Preston Lauterbach chronicles the tumultuous history of Memphis

In the opening pages of his new book, Beale Street Dynasty: Sex, Song, and the Struggle for the Soul of Memphis, Preston Lauterbach chronicles a fiery Civil War naval battle between a Confederate blockade runner and a fleet of Union gunships. Lauterbach focuses the passage on a twenty-three-year-old cabin boy who shared the last name of the Confederate ship’s captain.

[Robert Church] belonged to his father not only as a son but as a slave. Captain Church took care of him, though, and Robert enjoyed as adventurous and free an upbringing as was available to anyone, much less a Negro, in nineteenth-century America. Capt. Charles Church had instilled in his son a degree of personal pride, telling him, “Don’t let anyone call you a nigger.”

The contradictory themes and ironies contained in this opening passage are threads that run throughout Lauterbach’s fascinating history of Memphis and its most famous landmark, Beale Street. Keeping his focus on Robert Church, a former slave who became the South’s “first black millionaire,” Lauterbach relates the history of one of the great Southern cities from the end of the Civil War to the dawn of the civil-rights era. It’s a tale littered with dichotomies—vice kings and philanthropists, graft-driven politicians and progressive activists, human depravity and timeless music.

Lauterbach brings Robert Church to life through illustrations of the sharp contrasts in the man’s life. Intelligent, educated, and so light-skinned he could easily have passed for white, Church chose to remain in his home city even after gaining his freedom. Although limited by his race, Church was aggressive and inventive in seeking out business opportunities, forging alliances with white power brokers, and courting public opinion. In 1878, as Memphis was rebuilding after the Civil War, a devastating yellow-fever outbreak struck the city. Out of this tumultuous period, Church built an empire of vice that included booze, gambling, and prostitution. As Lauterbach writes, “[H]e reenacted on dry land what he’d learned on the river: serving white men’s thirsts.”

Church’s fortune and wily political machinations benefitted not only his family but also the African-American population of Memphis, and he established himself as a philanthropist. He funded socially-uplifting businesses, culture, entertainment, and public works, helping to establish Beale Street as the “Main Street of Black America” in the late nineteenth century. Under Church’s stewardship, Beale Street was a place where saloons, gambling dens, and white brothels flourished in close proximity to black churches and schools. Church’s financial patronage also extended to individuals, with his money benefiting a wide variety of characters, including progressive black journalist Ida B. Wells and bandleader, songwriter, and publisher W.C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues.” Church himself, Lauterbach writes, became “a symbol to the world that any man, even a black man, could succeed in the rebuilding city.”

Lauterbach presents the lively history of this period with meticulous research, an engaging plot that resembles a tense political thriller, and the white-hot language of hardboiled crime fiction. Consider this description of a white raid on a Beale Street gambling den.

Lauterbach presents the lively history of this period with meticulous research, an engaging plot that resembles a tense political thriller, and the white-hot language of hardboiled crime fiction. Consider this description of a white raid on a Beale Street gambling den.

A half-dozen early birds rolled the bones out of Hadden’s Horn amid marble-topped tables. Beneath paintings of naked ladies, they smoked and jabbered as the dice crackled over the green felt. It would be difficult to nightmare up a more dreaded scenario for a group of Negro crapshooters than what burst through the saloon entrance that Saturday night. Strange white men, with guns pointed, one peckerwood for each Negro. The dice froze, and trembling palms reached for the ceiling.

Lauterbach also focuses on the unique cultural atmosphere that nurtured the music of Beale Street. The jazz and blues born on Beale found an audience far beyond the theaters and street corners where it was created, and it persisted long beyond the lifespans of its makers:

This Southern black bohemia emerged simultaneously, more or less, to the highbrow Harlem Renaissance and made its own significant, if underappreciated cultural impact. Memphis Minnie and Joe McCoy singing “When the Levee Breaks,” Robert Tim Wilkins performing “Rolling Stone” and “That’s No Way to Get Along” … were common currency in Memphis during the late 1920s, songs that would return through Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead over forty years later.

After Robert Church’s death, his son, Robert Jr., directed the family fortune into building the most powerful black political organization of the early twentieth century. Using money and influence to register black voters, pay onerous poll taxes, and decide local and national elections, he created a political force that ironically would be brought down by progressive politicians and well-intentioned reformers.

Beale Street Dynasty delivers far more than just a history of a great Southern city and the struggle for civil rights. Lauterbach’s entertaining and enthralling tale breathes new life into one of America’s cultural landmarks, creating a beguiling portrait of American ambition, ingenuity, tragedy, and triumph.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.