In Search of the Moments

Greil Marcus turns his eye toward the music of Van Morrison

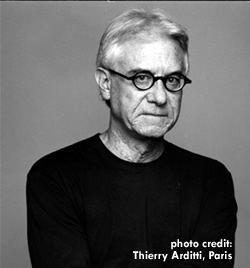

There are giants of rock and roll journalism—Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau, Robert Palmer—and then there is Greil Marcus. He isn’t simply a music critic. He is, as Nick Hornby calls him, “peerless, not only as a rock writer but as a cultural historian.” In Marcus’s writing, music is often the point of departure. Where the vehicle goes from there is anyone’s guess. But you can bet it will be an interesting, often thrilling, ride.

In 1975 Marcus delivered the landmark Mystery Train, a book which placed rock and roll within the context of the great American archetypes and would inspire countless cultural critics and rock journalists. He further solidified his status as a rock literary giant with Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century, Dead Elvis, and Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes. Marcus doesn’t write biography; instead, his writing often places art within a greater cultural context, whether that context is the notion of the American subconscious and the way Bob Dylan bootlegs comment on them, or the philosophical connections between The Sex Pistols and various separatist movements existing centuries before “Anarchy in the UK” offended anyone.

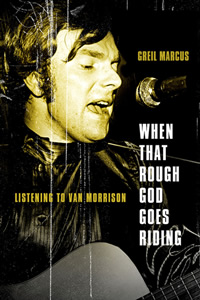

Marcus currently writes for Interview, The Believer, and occasionally teaches graduate courses at The University of California at Berkeley. His latest book, When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison, considers the indefinable moments in an enigmatic performer’s work where the artist transcends ordinary communication and reaches for the sublime. He took a break from his book tour to talk with Chapter 16 by phone.

Chapter 16: You’ve written, to great acclaim, about Elvis, Dylan, The Sex Pistols. In terms of pop-cultural iconography, Van Morrison seems an odd choice. Why him and why now?

Marcus: Well, I wasn’t interested in iconography, and it wasn’t a choice of what’s a subject that would fit with anything else that I had done. It really came about because I was interviewed for an NPR show about Astral Weeks. My wife heard it and said she liked what I’d said. She said, “That’s who you should be writing a book about.” That had never even occurred to me, and I realized maybe it was a good idea. This is someone I’d been listening to for so long, cared about, been thrilled by, and disappointed by. And the notion of diving into all his work and trying to find those moments when he seemed to realize the musical quest he had been on all this time—that just struck me as something that I wanted to do and that I could just sit down and write. You know, it’s not a biography; it’s not about his life; it’s not about who’s the real Van Morrison. It’s just a book about music, and it’s not an attempt to situate what he’s done in a larger context, but to try and listen to his music on its own terms and figure out what those terms are.

Marcus: Well, I wasn’t interested in iconography, and it wasn’t a choice of what’s a subject that would fit with anything else that I had done. It really came about because I was interviewed for an NPR show about Astral Weeks. My wife heard it and said she liked what I’d said. She said, “That’s who you should be writing a book about.” That had never even occurred to me, and I realized maybe it was a good idea. This is someone I’d been listening to for so long, cared about, been thrilled by, and disappointed by. And the notion of diving into all his work and trying to find those moments when he seemed to realize the musical quest he had been on all this time—that just struck me as something that I wanted to do and that I could just sit down and write. You know, it’s not a biography; it’s not about his life; it’s not about who’s the real Van Morrison. It’s just a book about music, and it’s not an attempt to situate what he’s done in a larger context, but to try and listen to his music on its own terms and figure out what those terms are.

Chapter 16: You write about the concept of the “Yarragh” throughout the book. Can you explain a little bit about that and the way it pertains to Morrison’s music?

Marcus: The notion comes from something John McCormack, who was a traditional Irish tenor, said. He was talking about the difference between a good voice and an unforgettable voice: “You have to have the Yarragh!” I’m not completely sure what he meant by that, if he simply just meant that kind of sound, that kind of roughness. And certainly, just as a sound, you can hear that all through Van Morrison’s singing from when he was with Them in the mid-sixties right till now. You know, he’ll make a sound like that—something that doesn’t need words, couldn’t be translated back into words, but it’s an expression of longing, of need, of frustration, of satisfaction. It’s just an expectoration in a way.

But the more I thought about it, the more that became a kind of signpost, the Yarragh! It meant, to me, when you make a breakthrough from ordinary communication, the way you and I are talking now, to something that seems so fraught with jeopardy, so full of possible meaning and gratification, something so scary that you can’t put it into words. You don’t even want to try, but you want to express it anyway.

And so I tried to see Van Morrison’s music over forty-five years as a quest for those moments when you had to leave behind ordinary communication and get across what you felt, what you wanted to say in a different manner. And that could be leading a band, it could be hesitations and pauses, it could be repetition—saying the same phrase again and again and again as he’s done all through his career, sometimes really casting a spell and sometimes just sounding like somebody saying something over and over again. So that became the grounding principal of what I was trying to do.

Chapter 16: Are there other artists you think would be good candidates for this kind of examination, where you’re looking at these particular moments? I suppose you could do that with any artist, but which ones would interest you?

Marcus: I’m going to write another book, pretty much on the model of this one, about The Doors. And it’s not going to be about the Yarragh. I’m not sure what thread will hold it together. But it will be like this one, not terribly long. It will be very different in the sense that with Van Morrison I had forty-five years of music to work with. With The Doors, I’ll have four. And that will be a different kind of challenge, to see if I can pull that off. Maybe you could do this with all sorts of people, but I don’t think you could focus solely on a person or a group’s music if there weren’t a sense of high stakes, if there wasn’t a kind of desperation and lust driving through it. Maybe someone else could write a book like this about James Taylor, but I certainly couldn’t.

Chapter 16: Some of our readers are likely familiar with only Van Morrison’s more well-known, radio-friendly work. What album would you recommend?

Marcus: I guess two. One would be St. Dominic’s Preview from 1972, which has so many different kinds of songs, so many different kinds of music on it. And yet it is so passionate if you can deal with someone who is just going to be wearing his emotions like clothes. And it’s also so smart, it’s thought through. There’s nothing casual about it. It’s not pretentious, not over-serious, but it’s just somebody doing his absolute best work. And that’s a long time ago, 1972.

Marcus: I guess two. One would be St. Dominic’s Preview from 1972, which has so many different kinds of songs, so many different kinds of music on it. And yet it is so passionate if you can deal with someone who is just going to be wearing his emotions like clothes. And it’s also so smart, it’s thought through. There’s nothing casual about it. It’s not pretentious, not over-serious, but it’s just somebody doing his absolute best work. And that’s a long time ago, 1972.

The other album I’d recommend is The Healing Game which is from 1997, and it’s very funny. But it’s also full of drama, this great historical drama about Ireland and Belfast, a place sort of forgotten by history and forced into conflict that will never end. None of that’s explicit; that’s just a feeling that runs through it. And you know it’s not an album that got a lot of attention when it was released. I don’t think it got terribly good reviews, and it’s so rich. Those would be the two I’d point people toward.

Chapter 16: I’m kind of surprised by that. I was almost sure you’d say Astral Weeks because it received so much attention in the book.

Marcus: Right, well people will find their way to Astral Weeks. I taught a class at Princeton four years ago. It was a seminar for undergraduates, so people were nineteen, twenty, about that age. I asked everyone to fill out a questionnaire with their favorite books and movies and music so I could just get a sense of who they were or what kind of frame of reference I’d be working with. And out of those fifteen students, four of them chose Astral Weeks as their favorite album. Now these are people who were born in the late eighties, twenty years after the album had been released. It’s conceivable their parents weren’t even born when the album was released. And yet this album had found them, or they found their way to it. So I don’t think I need to recommend that.

Chapter 16: You attended a performance of Astral Weeks in 2008. What were your expectations of that show going in, and were they met? What were your impressions afterward?

Marcus: You know, I don’t know that I had any particular expectations. When somebody sets out, doesn’t matter who it is, to recreate something that they’ve already done, that’s very chancy. It’s very unlikely that you’re going to be able to recapture the flare and the drive that brought you to the point where you wanted to do this in the first place. And that’s very different from being a performer and singing old songs, or bringing some old material into a show that is mostly new material, something like that. He was going to recreate this album. He was going to do it note for note, or as close as he could.

Ultimately that’s a completely sterile notion. And I think despite the fact there were fourteen musicians and they had rehearsed tremendously well, and the show was well planned and all that, it was sterile. It was fun to see this guy up there getting the recognition that he deserved, and I was happy about that. But there really was no whole song that took off, that made me feel you didn’t care where you were, how you got there, you just knew you were in the right place at the right time; that feeling you get at a great show. I wasn’t disappointed; I didn’t really expect anything more. But I’ve seen Van Morrison a lot of times, and this is not one of the times I’ll remember most vividly.

Chapter 16: You’ve been on book tour for a while now. How are audiences responding when you read?

Marcus: It’s really interesting. Usually when you go on a book tour and you do readings, people will ask questions. They’ll want to know something. Maybe they’ll want to know about the person you’ve written about in a way you haven’t written about that person. They’ll want some personal information or something like that. Maybe they’ll want to know why you did this as opposed to that. Maybe they want to ask about writing. But on this book tour—and this has happened maybe half a dozen, eight, nine places, everywhere I’ve been—people aren’t asking questions so much as they’re telling stories.

Everybody has got a Van Morrison story, and everybody is telling it, and they’re wonderful stories. They’re stories about going to a show and just being horribly disappointed, or approaching him after a show, or going to a concert and coming away feeling that you never want to go to another concert again because there’s no way it will be this good.

I think my favorite story was from a woman who’s probably in her forties or fifties, and she said she was talking to her father one night, and he said, “What are you doing tonight?” She said, “I’m going to hear this guy talk about a book he’s written on Van Morrison.” Her father said, “Oh, Van Morrison. You know I used to work with his father on the docks in Belfast. After work we got back to his house. He had this enormous record collection: blues, country music, old Irish singers, jazz. Just seventy-eights. Hundreds and hundreds of seventy-eights and LPs. We’d sit around and listen to those records and there’d be this little boy there, a two- or three-year-old boy, who’d be jumping around saying, ‘Play that one Daddy, play that one.’” Well, that’s not the kind of story a biographer is going to dig up. You can’t go looking for that, you just have to be grateful somebody offers it to you.

Chapter 16: Are these almost confessional responses making you think differently in terms of how you write about artists?

Marcus: I don’t know. I haven’t really thought about it. When I write, I sort of go into a trance. I don’t mean anything mystical; it’s just this very enclosed, psychological space. The real world comes back after the book is published and people react to it. I’m sort of not in a real world, [not] thinking about other people or other times and places while I’m writing.

Chapter 16: Do you have any idea if Morrison has read your book?

Marcus: No. You know, there’re some errors in the book—a couple of major typos and two or three factual errors. I imagine if he read the book, he’d say, “God, this guy doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about.” But I haven’t heard anything. I don’t know that he’s even aware of the book.