In the Company of Red-Tail Angels

A new history celebrates the World War II achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen

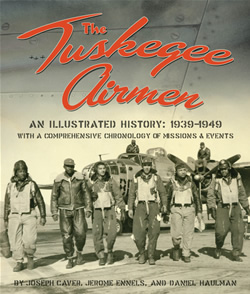

For most Americans, the words “Tuskegee Airmen” immediately conjure images of brave black fighter pilots in leather jackets struggling against racism at home and Nazis in Europe. Although generally correct, the image is an incomplete picture of one of the most remarkable stories of both World War II and the civil-rights movement. It is, in some ways, an exaggerated view of a highly decorated, though humanly imperfect unit. In their book, The Tuskegee Airmen: An Illustrated History, historians Joseph Caver, Jerome Ennels, and Daniel Haulman detail the history of the Tuskegee Airmen using photos and a never-before-compiled chronology of the training, deployment, and combat engagements of these celebrated aviation pioneers.

First, the debunking of a myth: the Tuskegee Airmen did, despite claims to the contrary, lose bombers they were escorting into enemy territory. In fact, enemy fire destroyed over twenty-five bombers under their protection. But the number of bombers lost by the 332nd Fighter Group was, according to these historians, “significantly less than the average number of bombers lost by the six other fighter escort groups of the Fifteenth Air Force.” This accomplishment, combined with the red paint on the tails of their planes, earned the 332nd the nickname “Red-Tail Angels” from grateful bomber crews. Among their finer moments, on March 24, 1945, an escort of Red-Tails succeeded in shooting down three Me-262 jet fighters, one of Germany’s “secret” weapons, a plane much faster than their P-51s. With such feats, the men of the 332nd undeniably dispelled the myth that black men weren’t as good at flying as their white compatriots.

Arising from the Civilian Pilot Training Program, begun by the United States in 1939 to create a cadre of qualified pilots in the event of war, the Tuskegee Airmen ultimately numbered 14,600 men, including 992 pilots. Their training began at the Tuskegee Institute but eventually encompassed over a dozen airfields around the country, some of which maintained segregated officers’ clubs and mess halls despite War Department policy. The common perception of the Tuskegee Airman as a fighter pilot is misleading – the name applies equally to the thousands of ground crewmen who kept the planes in the air. There were even four bomber squadrons, all of which were activated too late in the war to see combat. Today, veterans of the group have chapters in fifty cities, including Memphis.

Arising from the Civilian Pilot Training Program, begun by the United States in 1939 to create a cadre of qualified pilots in the event of war, the Tuskegee Airmen ultimately numbered 14,600 men, including 992 pilots. Their training began at the Tuskegee Institute but eventually encompassed over a dozen airfields around the country, some of which maintained segregated officers’ clubs and mess halls despite War Department policy. The common perception of the Tuskegee Airman as a fighter pilot is misleading – the name applies equally to the thousands of ground crewmen who kept the planes in the air. There were even four bomber squadrons, all of which were activated too late in the war to see combat. Today, veterans of the group have chapters in fifty cities, including Memphis.

The Tuskegee Airmen: An Illustrated History is not a narrative but an illustrated unit history, dominated by photos and captions and supported by a comprehensive chronology of events from 1939 to deactivation in 1949. The dozens of photos capture the men in training, in their off hours, and in their combat deployments to North Africa and Italy. It also documents the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen, a group, the authors note, that has “become part of the American cultural landscape.” They are men who earned their wings and a permanent place in the hearts of their countrymen.