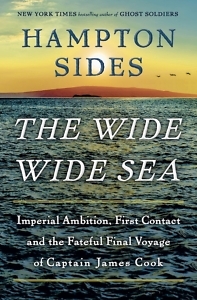

Into the Unknown with Captain Cook

Hampton Sides examines the final voyage of one of the great explorers

More than two dozen places around the globe are named for British Navy Captain James Cook. Most are places he visited in three major voyages of discovery in the late 18th century. But as revealed in Hampton Sides’ newest book, The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook, not a single one of those places was named by Cook.

Cook’s travels were driven by a thirst for knowledge, not glory. A highly skilled cartographer, Cook had, according to Sides, “an admirable habit of affixing an Indigenous name, when he definitively learned of one, to his charts.” And yet this self-deprecating explorer who respected the cultures and religions of those he encountered is best remembered today for being killed by Indigenous people he angered while making maps that paved the way for Britain’s imperial expansion.

Memphian Hampton Sides is one of the premier historians of our day, a man whose bestsellers range from polar exploration (In the Kingdom of Ice) to the Korean War (On Desperate Ground) and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Hellhound on His Trail). His novelistic style puts the reader into the action and the feelings of the participants. So it is with James Cook, the men he sailed with, his family, and those he met in his years of exploration. In The Wide Wide Sea, Sides brings to life all the excitement, drudgery, politics, and intercultural complications of the first interactions between the peoples of the Pacific and Europeans.

James Cook was an extraordinary navigator and cartographer, an officer respected by subordinates and superiors alike. He so carefully described the people and lands he visited that his work proved invaluable to subsequent generations. So renowned was he in his own time that during his third voyage, which began the fateful year of 1776, Benjamin Franklin issued a letter to American naval officers declaring that if Cook’s ships were encountered they should be granted any requested assistance. Even the American Revolution would not be allowed to interfere with Cook’s work.

But something was off during that third voyage. Cook behaved differently, was quicker to anger and less attentive to his navigation. The change worried his men. Floggings, the standard punishment in the Royal Navy, were administered with greater frequency. Even Cook’s relations with Indigenous people deteriorated. A cultural misunderstanding with the Maori in what was to become New Zealand caused serious problems. “For the rest of the voyage,” Sides notes, “Cook would show far less mercy and patience in his dealings with Indigenous people. Increasingly, he would become a despot, a hard-liner, with a mean streak that was seldom on display during his previous voyages.”

But something was off during that third voyage. Cook behaved differently, was quicker to anger and less attentive to his navigation. The change worried his men. Floggings, the standard punishment in the Royal Navy, were administered with greater frequency. Even Cook’s relations with Indigenous people deteriorated. A cultural misunderstanding with the Maori in what was to become New Zealand caused serious problems. “For the rest of the voyage,” Sides notes, “Cook would show far less mercy and patience in his dealings with Indigenous people. Increasingly, he would become a despot, a hard-liner, with a mean streak that was seldom on display during his previous voyages.”

Whatever the reasons for Cook’s change — Sides describes several theories — it all came to a head in Hawaii, whose people had never met a European. In Kauai, his first stop in the islands, all went well. So well, in fact, that the expedition planned to spend a winter in the islands. Cook anchored off the Big Island where the visit began auspiciously, everyone getting along. But it didn’t, perhaps couldn’t, last. The cultural differences proved too great, and events spiraled out of control. Cook became aggressive and badly misjudged the situation. Of the captain’s last moments, as Hawaiians closed in, Sides writes, “[P]erhaps, for the first time in his life as a commander, he genuinely didn’t have a clue what to do. He had drifted into another world that left him insensible to the dangers pressing in on him.”

The Wide Wide Sea is a first-rate tale of adventure. But it is also a tragedy, not just for Cook but for the Indigenous people of the lands he explored. He traveled for knowledge and the greater good, but many of those who followed his maps were not so noble. Sides acknowledges this, noting that, “Taken together, [Cook’s] voyages form a morally complicated tale that has left a lot for modern sensibilities to unravel and critique.” As a guide through such murky cultural waters, Sides is unsurpassed.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than 30 years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.