Inventing Ways to be Honest

Karen Russell talks with Chapter 16 about why she broke up with Amazon, how it feels to be on the shortlist for a Pulitzer Prize that was not awarded, and the distinction between fantasy and fiction

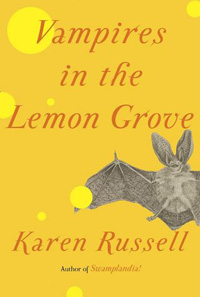

Karen Russell, author of Swamplandia!, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2012 (a year in which no prize was awarded), talks with Chapter 16 about her new collection of short stories, Vampires in the Lemon Grove. In her fiction, Russell toys with the line between fantasy and reality, and she is wary of fantasy’s association with young-adult novels. “Vampires in the Lemon Grove,” the collection’s title story, follows an immortal vampire couple as they struggle through marriage—a commitment that, for them, is truly and actually eternal. In this interview, Russell discusses her time in Germany, human mortality, the pros and cons of finding a bootleg copy of her own book in New York, and how writing is a delicate act of distortion and illusion.

[Editor’s note: this is the gently edited version of the interview. To hear the podcast click here.]

Chapter 16: So, the book has been has been out a week now?

Russell: It feels like I’m in some sort of Hopi time. I’ve been traveling around for a couple of weeks now, so I can’t quite remember my life before the book came out. I’m like, “It’s always been out, Stephen.” But I think the official release date was February 12.

Russell: It feels like I’m in some sort of Hopi time. I’ve been traveling around for a couple of weeks now, so I can’t quite remember my life before the book came out. I’m like, “It’s always been out, Stephen.” But I think the official release date was February 12.

And a friend just texted me—I don’t know why this made me excited—a picture of a bootleg copy, you know they put up those card tables in New York? So it’s been bootlegged! They had bootleg Teddyand then my book was next to it. I don’t know why that’s a metric of success, but I was excited.

Chapter 16: How much would you pay for a bootleg of your book?

Russell: I can’t give that thing away to my family members. They’re like, “We’ll wait for the paperback,” and I’m like, “I’m giving you a hardcover. You don’t have to buy it.” I would insist on paying the full [price for a book]—it’s not a great thing that [the bootlegging] happened, in fiscal terms. I don’t know how the bootleg happened, but it’s astonishing that someone would think there would be a market for a bootleg short-story collection.

Chapter 16: You are selling well on Amazon. I saw the numbers were pretty high. You’re in the top 100.

Russell: Oh, Amazon and I had to break up after Swamplandia!. That just became a place I can’t go.

Chapter 16: Because of trying to keep track of numbers or [because of] the reviews?

Russell: I think all of it. I don’t even know exactly what those numbers mean. I think it’s like if people have a dysfunctional body image and they keep watching fluctuations on their scales. Reviews are a little dangerous because they can snake their way into your brain and then you can’t forget that. So [you] give the most credence to someone who’s like, “Half a star! I chopped this book up with an axe and then taped it back together and turned it in for a refund.” I always remember those.

Chapter 16: I’ve asked this question before, but how many good reviews does it take to make up for a bad review?

Russell: It’s just so interesting to monitor the way that you process the echoes coming back, if you put a book out. I really believe that afterSwamplandia!I was inoculated because there was such a volume of really diverse feedback, where some people seemed to really like certain parts of the book. Some people just hated it, said it was the worst thing they’d ever read. Some people were encouraging. It was like some kind of Freudian cure. It was like an exposure cure, where I was like, “Oh, good, I’ll put these stories out, and I’m going to be basically even keel and not pay too much attention.”

I still feel pretty vulnerable. I think the danger is in both directions—that you start believing either thing. I think you don’t want to get too attached to a great response or a negative response. In a really micro way, I used to feel this at the workshop level as a student, where there would be a story that was a huge hit with some readers and then not with others, and you’d be like, “Yeah! I’m something of a phenomenon!” or, “Oh my gosh, I’m the worst writer! I should turn in my pen and only use spoken language from this day forward.” I think either response is not the place you want to be writing from.

Chapter 16: Well, you can never be all things to all people.

Russell: I just think that the pendulum swings between some kind of grandiosity that lasts for two seconds and then wallowing despair. Neither of those states is great for writing.

Chapter 16: So, what happened with the Pulitzer—was that a good tempering, that “Yay, I’m a finalist! But I didn’t win. But nobody else won, either.”

Russell: To be honest, I think I’m still processing now. It wasn’t so terribly long ago. You don’t know you’re a finalist beforehand, so I sort of found out at the same time everybody else did. Mercifully, I was abroad, so I think I was a little bit out of the loop in terms of media response and stuff like that.

Russell: To be honest, I think I’m still processing now. It wasn’t so terribly long ago. You don’t know you’re a finalist beforehand, so I sort of found out at the same time everybody else did. Mercifully, I was abroad, so I think I was a little bit out of the loop in terms of media response and stuff like that.

I think my takeaway was just to feel kind of shocked—it was it was never anything I imagined would be possible—and grateful to the three nominating jurors who put it on that short list, just out of bounds grateful to them. And then I tried to keep my head down a little bit because to engage with a lot of the controversy and speculation probably can’t be good if you want to write something new. I told my friend it was a little bit like eating a grenade sandwich. I felt a lot of things all at once. I just kind of shut down the computer for a little while. I learned in the same instance that I had been a finalist, which was sort of unbelievable. But, also, that’s in this year when no winner [was announced]. I’m sure everybody who read that news had exactly my same set of speculation about what might have happened. I have no more information than anybody else. I think the thing to retain is to feel encouraged and grateful to the judges who paid me this huge compliment.

Chapter 16: I only read your book of the three finalists, and I would have voted for you.

Russell: Thank you, I appreciate that.

Chapter 16: But you did win a National Magazine Award last year as well.

Russell: That was amazing, too. That was for one of the stories in the new collection. I was really excited about that because one of the pleasures of writing stories is you get to work with magazine editors pretty closely, and I worked with Michael Ray at Zoetrope who had also edited the title story with me, and did “Ava Wrestles the Alligator,” which is the story that spawnedSwamplandia!, so I was just happy that we got to high-five on that one. We worked closely on umpteen drafts of that story—“Proving Up”—in the collection. It was called “The Hox River Window” to give it more of a horror story-feel for their magazine. There’s no overstating the heroism of editors at places like Zoetrope.

Chapter 16: Were there other things in the stories that changed from the original publication to their appearance in their collection?

Russell: I think I might have added one line or two, just to be finicky [and] just because I got attached to them. I think that if people saw the original draft, that would be another kind of horror story. It really took a long time to hatch that guy out, and we changed so much from the original—it used to be written in third person. The tone wasn’t consistent. It’s all boring, behind-the-scenes stuff, but it did undergo a massive change when I was working with Michael Ray. And once we [finished it], I didn’t want to touch it. There are other stories in the collection that I did fiddle with more.

Chapter 16: I remember when we talked about Swamplandia!, you talked about [having to] take out so much stuff you’d included in your research about crocodiles and alligators. So was there a lot of stuff about the Homestead Act that you had to take out of “Proving Up”?

Russell: I must have been really traumatized when we spoke, because at that point, I was at the apex of my herpetological knowledge, and it was painful to me that I had amassed all this knowledge about alligator mating dances and their digestive systems. That [knowledge] had no home.

I feel lucky. The “Proving Up” story was an offshoot of research I’d been doing for this second novel, [which] is set during the dustbowl. It’s like an agrarian horror story about what we can endure. I still labor in the delusion that the stuff I’ve learned is stuff that I can find a home for in the novel. My editor, she’s like, “That’s so fascinating what you learned about the history of barbed wire, but it really doesn’t further the plot in any way. Get that out of there.”

I just learned quite a bit about Meiji-era Japan for “Reeling for the Empire,” a lot of which didn’t make it into the final story. That one about the presidents who are reincarnated [“The Barn at the End of Our Term”]—people have written trilogies about each of the presidents that get reborn. As fascinating as that trivia is, it doesn’t necessarily seem relevant for this twelve-page weird story.

Chapter 16: In a way, your stories remind me a little bit of Jim Shepard’s short stories, in that there’s just so much research that goes into them that they’re almost miniature novels.

Russell: I love Jim Shepard, and so I’m flattered by any comparison to him. But I’m J.V.—Jim Shepard is the master, I think, of the historical short story, and I love that he’s gotten so much attention from them. They have the impact of a novel, I think, every one of histories. He’ll take you from the Korean front to some Nazi yeti hunter to Australia. Andrea Barrett is someone else who can do that. Often they’re a little straighter, insofar as it really is pretty representational of history. There’s not some talking Minotaur wandering around. But not always in Jim’s case, I think. He’s someone who’s a huge influence. All of his [work] reads to me like he has done us a service of digesting fifty-seven diaries of Arctic exploration or prairie life or French executioners.

Chapter 16: You mentioned that you do tend to include some fantastical elements into your stories, but don’t you consider fiction—almost all fiction—is a fantasy of a sort?

Russell: Yeah, it is. It’s been interesting this time around because as with Swamplandia!, people want to talk about the fantastical and the real as if they’re these definite, distinct categories. And obviously, even you’re writing memoir, it’s still unreal on the page. George Saunders has a nice quote about how all writing is compression and distortion and that it’s all strategic. Realism is just one strategy to provoke emotion in the reader, and that [realism and fantastical] are just different strategies.

I was thinking about visual art: someone is painting water lilies that more or less resemble the water lilies you could walk outside to see. Maybe Salvador Dali had some melting phantasmagoria. It’s still kind of assembled out of terrestrial reality, it’s just represented differently to highlight different pieces. But I do think there are ways you can fit up that ratio of naturalistic details that feel closer to the world that we occupy or closer to actual recorded history. And then some things that we would consider impossible—an afterlife where a bunch of presidents are reborn as horses—nobody’s necessarily been to a place like that. It’s different to set a story somewhere like that than regular Kentucky. But both are fantasies, both would be unreal, if it’s a fictional universe.

Chapter 16: Even the concept of someone saying that something doesn’t seem real when they’re looking at these pigmental squiggles on a piece of wood pulp or on an electronic screen, and you’re going, “This is supposed to be reality? Squiggles?”

Russell: It’s so funny. And I think you can lose sight of that, actually; writers are always making it up,and they’re always ordering words on a page to create illusions. That’s the name of the game. For whatever reason, I think writers are always trying to invent ways to be honest. To set the thing up on the page, to set up a world where they can be honest about something that they find genuinely preoccupying or mystifying. Some question that they have themselves about their “regular” or “real” life.

For me, it’s just always felt more possible to say something that feels honest or to which I have a genuine emotional connection. I might have said this about Swamplandia!, too, but if I was trying to write a historical fiction about Florida set in the Everglades, I think I would feel so panicked about getting it right. Or I’d feel so beholden to the laws that govern the everyday, and I think that would be deadening to me; there would be some creativity that I would forfeit if I were trying to do that. Franz Kafka—why wouldn’t he just write the story of Gregor Samsa who had an amputation, or some terrible illness, or has a psychotic breakdown or is transformed in some way that is plausible, that isn’t that he’s turned into this giant bug? I just think somehow, whatever that invention—whatever that monstrous transformation that Kafka thinks through—it felt more natural to him to do it in that register than in a “realist” mode.

Chapter 16: How do you attribute the fact that you utilize fantastical elements and are accepted and praised in the literary community where other writers may not make that crossover?

Chapter 16: How do you attribute the fact that you utilize fantastical elements and are accepted and praised in the literary community where other writers may not make that crossover?

Russell: I feel lucky that there’s a readership and that people have taken my work seriously even though, superficially, work often gets discounted if it has adolescent protagonist. People want to call any fiction that has adolescence floating through it YA, and I think if you have any kind of supernatural elements or magical—lately I’m worried of that word because I think people hear “magical” and they dismiss it as, “Oh, it’s kid’s stuff. It’s whimsy without any kind of consequence.”

Honestly, I don’t know how I’ve been so lucky that people have taken what I’m writing seriously because I take it pretty seriously, and I often have real ambitions for these stories, or there’s some larger question that I think even the silliest ones are concerned with. It’s my hope anyway that readers pick up on that—that it’s not just a lark or a bad joke that goes on too long or an exercise in gimmicky inventions. There’s some genuine-enough, and genuinely dark, question fueling the story or, in the case of Swamplandia!, that book.

Chapter 16: You’ve mentioned that you’ve used adolescent protagonists in a lot of your work, but the title story, “Vampires in the Lemon Grove,” seems like an overcorrection: you’ve got characters that are well over a hundred years old.

Russell: Yeah, and I think also “The Barn at the End of Our Term” [had] the same problem, where I consciously decided I can’t write another story where the narrator is a first- person thirteen-year-old boy, some wacked-out teenager. Then I wound up with this story about the souls of dead presidents, and I just didn’t see that coming.

It’s funny, because I also think that Clyde—this hundred-year-old vampire in the first-ever adult love story that I tried—is in some ways pretty stunted. He’s pretty fragile and stunted, and there are aspects of his character, despite his millennial age, that feels useful to me. It does feel underdeveloped, in part because so much of his existence he spent enslaved by cravings, but he really was in this violent cycle, and he wasn’t growing up. I think it was meeting this woman that helped him to let go of these myths about himself and begin to grow up, even though, at the time of their meeting, I think he’s one-hundred-and-fifty.

Chapter 16: You think about it, and what is maturity? One of the aspects of maturity is understanding one’s own mortality. And if one is immortal, can one achieve that?

Russell: I was thinking about that a lot. I think that story gave me a place to consider the role that the foreknowledge of death and that the developing awareness that it’s not a joke, that you’re really going to die and everyone you love is going to die. How that matures you, and what mature love would be if you really are making an eternal commitment to someone, and what kind of special challenges that would cause. In a way, I think it [shows] how interesting, how mysterious death would look to this eternal, undead dude, and this morbid longing he might feel, or his curiosity to know how death would be possible. [For Clyde] it looks almost impossible that humans would love one another and make that kind of commitment while aware that they are definitely going to lose each other to death.

Chapter 16: I once wrote a review—there’s a punk band back from the ‘90s called The Dismemberment Plan, and they were from the D.C. area, where you are right now, and they were kind of artsy. They weren’t brutal or really mean-spirited in any way, and with halfway-literate lyrics. But they were breaking up, and I wrote a review of the concert, and it was the concept that I was an immortal being who was at this concert on their farewell tour, and saying that even though that I’m immortal, I don’t have immortal memories. The memories do fade, even for someone that’s immortal, and that there would only be two or three things I would take through the entirety of my existence, and those would be aspects of that concert.

Russell: Wow! How did you come up with that? That’s incredible, to crack a persona that’s immortal but just as prone to senility as we are.

Chapter 16: Well, it was just thinking about the transitory nature of existence. I was going through a break-up at the time, too, and seeing that go away and knowing that everything doesn’t last. Everything is transitory. And projecting those feelings of loss to the feelings of loss one would feel over the centuries to one’s memories, and what’s the definition of self other than experience?

Russell: And your accumulated history. That’s so interesting. I think a lot of the stories in this collection are obsessed with exactly that, how even the past can be taken from you, right? How nothing is immutable and fixed, but if you’re just sort of a collection of memories and stories, and you’re the least reliable narrator of them, even the ones you cherish [and] want to preserve or you feel some kind of grim obligation to. Even that entropy you can’t stop.

Chapter 16: Well, I was thinking about Clyde. He’s a vampire that no longer drinks blood, and to us from the outside, drinking blood is one of the defining characteristics of a vampire. So, if you’re not fulfilling one of your defining characteristics, are you that thing anymore?

Russell: I was just thinking about the kind of resentment that that might create inside a relationship. I wasn’t thinking about it as it a direct one-to-one, but if you give up an addiction—or you have some undead alcoholic, some dry drunk guy: as horrific as his life as an alcoholic may have been, he now comes to find that he is squishy, nameless, new entity. This thing that felt so essential to his identity is gone, so there’s freedom in that, but there’s a real terror, too. I think a lot the characters in many of these stories are exactly in that limbo where some story is broken down or a myth is dissolving: it’s lost its hold on you, so there’s a freedom that comes with that, and there’s also this responsibility that I think many people shirk to tell a new kind of story, that’s going to commit them to move on and not get paralyzed and not get trapped in traumatic repetition of the same old story from the past.

Now I feel like there’s some sort of amazing series of reviews to be written from the perspective of this immortal. I would love to see out of that guy’s eyes at a concert or a film, or what little gemstones he’s going to polish up and keep with him for as long as he can.

Chapter 16: And at least he has a short memory. He has seen everything before, but at least he’s forgotten that he’s seen it so he can enjoy stuff again.

Russell: I know, that’s a funny mercy, right? So he’s not just like, “Yawn city! Nothing can surprise me, I’ve been around since the dawning.”

Chapter 16: Our ability to forget is one of the greatest gifts ever given to human beings.

Russell: I think there’s a panic in all of my stories about the tides erasing even your worst memories, or you know, the tides erasing a loved one, so that gets taken from you—their sense of a physical presence or a memory that you’re even afraid to think about too much, because the action of that nostalgia distorts the weave of the memory. [Like] the way you wouldn’t want to palm a photograph too much or expose it to the light. I think a lot of these characters have a real sense at how fragile the past is, and how the past is a fiction, like you were saying.

Chapter 16: Is there a way you think the outside world might see that if you gave that up, you would still be yourself? There’s a sense identity imparted on you by the outside world, but you can lose that and still feel like Karen or however you conceive of yourself.

Russell: This is a funny one. When I was in Berlin, last year, one of the things that I best liked about it—I stuck around in the summer—nobody had any idea about my history. Nobody knew me as anything but this short, awkward brunette wandering around, speaking terrible German. And there was such a freedom to that anonymity, right? Because I think for the past several years a lot of my feelings with new people and strangers have all been mediated by these books—which is amazing and a gift, but also kind of disorienting. It was sort of a relief to see that I still felt like a coherent girl in the world, even though nobody had any idea, didn’t know where I had gone to school or what jobs I had. Didn’t know my family or where I was from. Didn’t at all know that I was a writer. Nobody had read anything I had ever written.

I don’t know, I think that would be sort of a loss. I think that would feel like an amputation at this point, if I had to give up writing for whatever reason, because it’s so much of my identity now. I’ve sort of stayed in that and that’s always been—long before I published anything—my favorite thing and how I understood the world, so that would feel like quite a loss, to be exiled from writing or language.

Chapter 16: So what was your favorite German word that you learned while you were there?

Russell: Oh, I like this expression: entschuldigung. [It’s] what everybody says when they bump into you. And I was told that it means “un-guilt me.” That might not be the real translation but it seems like a Charlie Brown spell or something. I am always guilty, just riddled with guilt about a million different things. I like that there’s this word for “un-guilt me!” Like someone can take the hex of that guilt right off you.

Chapter 16: Well, it’s “excuse,” so you “excise” the “cuse” out of there.

Russell: Yeah! Like an exorcism of whatever guilt you should feel because you just knocked into an elderly woman.

Chapter 16: I lived in Germany for a little while, and my favorite word as a concept was doch. And that is a refutation of a negative question. So if someone asked you a negative question, say, “You don’t have any money, do you?” You say, “doch.” You say, “I have the money.” Because, in English, if someone asks you a negative question, however you answer—it doesn’t quite sound right because you don’t know if you’re confirming what they’re saying or going against what they’re saying.

Russell: That’s amazingly useful, right?

Chapter 16: The only word that kind of comes close is saying, “Actually.” “You don’t have any money, do you?” “Actually, I do.”

Russell: That’s such a neat tidbit to be able to pull off in a sentence: doch. You know, there were so many great compounds, too. Of course, I’m blanking on them now. But I like those endless compounds.

Chapter 16: There was one I saw in a magazine, in an advertisement. And it’s my favorite kind of mash-up word:Heizkörperverkleidung.

Russell: Oh my God, what’s that mean?

Chapter 16: It’s a radiator cover, but it’sheizkörper,which means “heat body.” And verkleiden means “to cover up.” But it’s just one big old word: heizkörperverkleidung.

Russell: There was one that I can’t remember now, but I liked it, too, just conceptually, where you feel shame for someone who is so socially out of it that they don’t even know that they should be ashamed. Like, you take on the shame of someone who is so shameless that they’re incapable of shame.

Chapter 16: I learned a phrase recently. I have a real problem with humor that’s based on embarrassments. So, a show like The Office or something like that, where’s there’s so much about the grimace.

Russell: I know, me too. I couldn’t even watch. Remember when that grandma would fall down in the commercial? The “Help, I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!” And then everyone would parody that? But I was so uncomfortable for the grandma. I was like, “Everyone, she was someone’s real grandmother!”

Chapter 16: The phrase is “vicarious embarrassment.”

Russell: That’s it, that’s the one I’m trying to come up with. It’s a German’s word for exactly that. Vicarious embarrassment. Yeah, you have too many mirror neurons or something. You’re just aflame on behalf of the other party.

Chapter 16: In the story “The New Veterans,” a congressperson named Eule Wolly purposes a bill that makes sure veterans have access to massage therapy. Now, in making up that name, were you challenged by real congressional names to make it as ridiculous as possible?

Russell: No, that must be some kind of perverse impulse on my own. I mean, there really has been some [arguments for] direct access to chiropractic services and massage therapy for veterans, all of which I think are great. I was just thinking in the case of this self-serving man who is co-opting the real suffering of these veterans for his own glorification in the end. Doesn’t that just sound right? Eule Wolly—Wolly is such a stupid surname. I think this must have come through in the one about the presidents as horses, too. Some disconnect between men’s self-regard, you know, the nostril flare of self-regard of the politician. It’s some kind of animal vulnerability or just the way you get the sense they’re not seeing themselves accurately.

Chapter 16: There was another name that caught my eye, and it was in “The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis.” Larry Rubio’s mother’s maiden name was Dourif. And that reminds me of the actor Brad Dourif. A lot of people know him from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,but I always remember him for playing Hazel Motes in the film version of Wise Blood.

Russell: Oh, wow. Do you know, I haven’t seen that? I would love to see that. And isn’t that a name! Hazel Motes? I love Flannery’s names. I think she had a gift. Enoch from “Enoch the Gorilla.” It’s just strange on the page to see that name.

I honestly can’t quite reconstruct [naming] a character. I usually need it to be idiosyncratic in some way. Derek—that’s one of the straightest names I’ve given a character. Usually I want Clyde or Magreb.

Chapter 16: In “Proving Up,” the story you won the award for, you’ve talked about your humor. Oftentimes, I have to laugh out loud when I’m reading, but that is one of the most bone-chilling stories I’ve read in quite some time.

Russell:I’m glad it worked that way. It’s often hard for me to do straight dark. It doesn’t feel necessarily all that natural. “Reeling for the Empire” was another one where there used to be half a joke in that story and we cut it in the editing process. That was a little bit different with this collection. There are a few stories where there’s not a lot of relief in the form of humor.

But I think there is something so chilling about some of the accounts from that period. And what was the scariest to me was just a psychological dimension of a hope that’s deathless, a hope that’s outlasted any chance for its fulfillment and it’s become fatal to its host. You read some of these stories and you see the literal sunk cost of all these dead children, dead relatives, seven seasons of drought. There’s no money, there’s no food, there’s no water. And there’s no chance that these families are going to leave the land. I mean, they’ve staked their claim in a literal way. For me, that was the horror part of the story: something we often celebrated as virtuous, which is a hope that won’t quit, and in this case, it becomes monstrous for this family.

Chapter 16: Being punished for that yearning for freedom and for the frontier.

Russell: Right. Or there’s been some kind of fundamental mismatch between this family’s beautiful dream and the landscape they’ve chosen.

I guess I like it because it’s very literal. They do stake a real claim. It’s not figurative seeds; they’re planting actual seeds and hoping. And then this blindness settles in, where if you’ve already sacrificed so much it becomes impossible sometimes to admit defeat. And then I think cowardice and courage are just on a slippery spectrum.

It’s funny because the setting and the time are so different, [but] I once again think there’s some kind of connection to the same kind of central drama in Swamplandia!, where there’s this family that keeps clinging to this American dream that he’s going to be self-sufficient, he has his business and he can protect his kids from this cracked mainland reality, and it ends up exposing him to all kinds of danger and sending his kids to this real hell. And in a different way, I think that’s what happens to Miles in the story “Proving Up.”

Chapter 16: It’s an interesting concept: the cowardice of tenacity. Because you don’t know when to give up.

Russell: And that might not even be the right word—something shifts, and that optimism becomes delusion, and that kind of courage and forbearance becomes something else—something really dangerous. An inflexible hope that can’t accommodate this new reality.

Chapter 16: Yeah, you don’t have the courage to change. And also, just the utilization of the window—this common window they have to share because there’s a requirement in the Homestead Act that the dwelling has to have a window. It’s that fact that a window is a form of protection to keep the outside out but also to allow the outside world to be visible, and to let light in, and that they become blinded by this window.

Russell: Metaphorically, who doesn’t love a window? I was so excited because that’s a real clause in the Homestead Act, that your house has to have a glass window, which initially struck me as insane and finicky. And then I was thinking, like you said, it’s the membrane of the house, where you’re publically visible to the community and they can see in. You’re protected but you’re visible, as you said. So it does seem kind of requisite, [that] to be considered a part of a community you would have a window, a way of seeing in and out.

I think so many of these stories are about people whose sight has become distorted, by hopes or fears. In some way, their vision has been compromised by something internal.

Chapter 16: Can you recall the last thing you’ve had your vision compromised by?

Russell: I guess there’s little and big answers to that. I’ll get caught in the etiquette-to-crisis slide, where I got into a taxicab and it just seemed like something was awry, but you don’t want to make a fuss, so you just want to go along. I was supposed to go to the Harvard bookstore, and these roads were very obviously not Harvard. That’s a micro example, I guess. There were a million points on the timeline where I could have said something and didn’t, just because I wanted to be polite. That’s a very, very silly example, but time shoots you off. Two roads diverge in the woods one day, and your envisioned destination and where you end up—they can just be very different. It’s incremental, right? The mistake grows exponentially, second by second, but there’s no point where you’re doing anything so grievously wrong. I think it’s that spectrum.

Chapter 16: Well, thank you for being polite enough to not point out when our conversation went off track.

Russell: I want to have a good answer for you, like I was involved in some kind of land scam, and I believed that there was oil in Texas and pitched in. Or I fell for that Nigerian prince scam; I was so excited to have Nigerian royalty that was my blood kin that I sent a bunch of money when I got that email. I want to have some really specific examples of how I was duped by my greedy, greedy hope.

Chapter 16: Surely you’ve got to have some gullibility in you; you’re a writer.

Russell: I feel like the most gullible person alive. I’m sure the reasons I keep writing these chronically bewildered characters is because I’m so incurably credulous. Maybe we shouldn’t even have this part of the interview because I’m the most easy-to-dupe human. Just now, I was trying to send a fax—which I didn’t even know you could do anymore; I thought that was a thing of the ‘80s, but it turns out I had to send a fax—and I was asking somebody at the front desk if there was a Kinko’s around here, and they said, “Why don’t you use your phone?” I think they meant that I should use my phone to locate a Kinko’s. I was like, “Oh, wow! You can use a smartphone to send a fax? How do you do that?” I’m an easy mark.

Chapter 16: You mentioned your work with the project on the Dust Bowl; where does that stand?

Russell: I’m back there now. I think it was necessary to try out some of these other voices and centuries in this story collection. I was so happy working on these stories again and writing some new ones. It was good to do “Proving Up.” Somehow, the emotional heart of that story, the horror story we were talking about—why do people stay, how much can you endure and still go on?—that was an interesting micro place to think through some of the bigger themes in this book.

Now I’m back there. Say a prayer for me. It’s as confusing as it was when I departed. I’m hoping after this book tour, when I’m done, I’ll really like to settle in again and try again. Writing a novel, it just feels like those people who failed to summit Mount Everest the first time, but they keep going back. That’s how writing a novel feels to me. Or for some perverse reasons, you’re like, “Time to go to that freezing, exhausting place. See how high I can get.”

Chapter 16: But you’re getting something out of it, somewhere, surely.

Russell: Oh, I love it, too. It’s exciting. It’s a different sort of creature from Swamplandia!. But we’ll see how it all shakes down.

Chapter 16: Well, I better let you go for your appearance.

Russell: It was a real pleasure.Those were some hard, good questions. I’ll be thinking about them.

Chapter 16: Thanks for thinking about them later, when we’re not actually talking.

Russell: No, no. They’re really hard, right? The one about which parts of your identity could you let go of and which would be shattering to lose. That’s a tough one. I was going to say that I was on Chapter 16 today because my friend Adam Ross has this amazing essay up there. And he kind of echoes a lot of what we were talking about, in terms of fantasy in fiction and all fiction being curated fantasy. That it’s always the imagination being curated by somebody’s consciousness.

Chapter 16: And to bring it full circle, a couple of years ago I was over at Adam Ross’s house, sitting on the back porch, having a beer with him and Jim Shepard.

Russell: Wow! It’s neat to me that the people who engineer these worlds that you love to spend time in—they’re just human men in the world. That’s always the most shocking to me, that it’s just a guy in a sweater who, in his down time, has produced worlds that other minds can occupy. It’s a cool thing.

Chapter 16: Well, think, you do the same thing. Do you not feel, yourself, human?

Russell: Until relatively recently, my contacts with writing were all from a reader’s perspective. Someone gave me a painting—it was her painting of Swamplandia!—and I was so thrilled because you never really get that. You never get a visual representation of what another mind did with your words. And, I have to say, it’s very different than the Swamplandia! that I imagined writing. But that’s the mysterious, amazing part, that she could read that and make this amazing place that’s its own thing. It’s a spooky collaboration.