Invincible Language

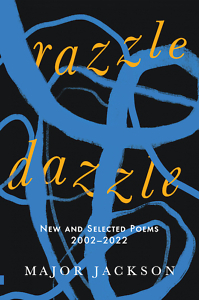

Major Jackson’s Razzle Dazzle combines new and old poems to dazzling effect

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on September 18, 2023.

**

Major Jackson possesses an almost superhuman ability to see himself and his world clearly. His sixth poetry collection, Razzle Dazzle: New and Selected Poems 2002-2020, reads like a superhero’s origin story.

We see the biographical details of the poet’s life alongside the evolution of his poetic style. In “A Promise of Canonization,” he writes, “I quote Wordsworth, Zagajewski, and Dao / I come from gunshots and beatdowns, raw and dirty.” Here and elsewhere, Jackson positions himself between spheres, ultimately showing us that everything is worthy of this poet’s searing gaze.

The new poems here, collected in a section titled Lovesick, are elemental: necessary as well as preoccupied with wind, water, earth, and fire. “Let Me Begin Again” sets the tone, proclaiming, “This time, let me circle / the island of my fears only once then / live like a raging waterfall / and grow a magnificent mustache.” This opener is so, well, dazzling that it’s hard to imagine the following pages sustaining that level of energy, yet they do.

I’m often drawn to debut collections because of an ineffable quality that lies somewhere between recklessness and exuberance. There’s a riskiness created by lack of outside pressure. Of course, most writers hope to publish their work, but those first forays onto the page can be wild and maybe even pure. We see this in Jackson’s first collection, Leaving Saturn. More surprisingly, we also see that edginess in Lovesick alongside the poet’s signature technical mastery. In “Making Things,” the speaker explains, “I want to be / all razzle-dazzle before the dark-cloaked one / arrives for a last game of chess.” While Jackson’s work may have matured over the years, it certainly hasn’t mellowed.

There is a leitmotif that appears in Lovesick that, if present, is not as prominent in Jackson’s earlier books. The notion of kindness is mentioned more than once. It exists in parallel to rage, again pointing to the poet’s duality. The prose poem “Ferguson” reimagines the killing of Michael Brown as a fairytale in which a teenager isn’t murdered. Instead, the young man has decided to sleep in the street for a spell. Spectators watch with bated breath for him to rise. “The police,” Jackson writes, “cordoned off his body, and after some time, declared him dead because they had only seen black men lying prone on the street as corpses, but never as sleeping humans.”

In the poem “Think of Me, Laughing,” the speaker describes himself at a protest, saying “Don’t shoot!” The poem then shifts into memories described as luxuries, including aperitifs in Italy and singalongs to Marvin Gaye. The speaker states, “I do not regret my little bout with life,” which seems to be a sort of radical kindness to the self. “Invocation” begins, “Down here we have inherited an arcade of stars / and want kindness that can stop a bomb.” In other hands, this theme might feel saccharine or, worse, disingenuous. In Jackson’s capable ones, we find kindness as a weapon, ready and sharp.

In the poem “Think of Me, Laughing,” the speaker describes himself at a protest, saying “Don’t shoot!” The poem then shifts into memories described as luxuries, including aperitifs in Italy and singalongs to Marvin Gaye. The speaker states, “I do not regret my little bout with life,” which seems to be a sort of radical kindness to the self. “Invocation” begins, “Down here we have inherited an arcade of stars / and want kindness that can stop a bomb.” In other hands, this theme might feel saccharine or, worse, disingenuous. In Jackson’s capable ones, we find kindness as a weapon, ready and sharp.

Jackson currently serves as poetry editor at The Harvard Review, and in January 2021 — after 18 years at the University of Vermont — he joined the faculty at Vanderbilt University as the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities. Lovesick includes “Nashville Sonnet Deconstructed on a Bed of Magnolia Blossoms,” in which Jackson writes of his new home city with references to pedal taverns and heartbroken singers. The construction cranes speak “an invincible language.”

Razzle Dazzle is arranged so that the newest poems are followed by the oldest. Leaving Saturn was released in 2002 and beloved by critics and readers alike, myself included. What I remember most about my own early reading experience is the phrase “tragically hip” being a perfect description of the book’s ethos. The speaker of “Blunts” recalls smoking weed for the first time and confessing to his friends that he wants to be a poet. His friends consider this goal as they hear yelling from apartments above, smell hotdogs down the street, and watch plastic flap on a shopping cart. The effect is immediate: The young poet’s ambitions are at odds with his surroundings. And yet his friends don’t laugh. Instead, one suggests, “So, you want the tongue of God.” Looking back, it’s clear that Jackson has always been concerned with the gap between physical and intellectual worlds, suggesting that they exist in tandem.

Leaving Saturn established Jackson as a leading voice of contemporary American poetry, so it’s no wonder that his follow-up, Hoops (2006), probes that position. The poems in rhyme royal (Chaucer’s creation) engage with literary and hip-hop canons. There are deep-dive conversations with writers like Gwendolyn Brooks, punctuated by fly-by references to performers like Tupac Shakur and Lauren Hill. Jackson drives the classic form as if he has one hand on the wheel, the other making a beat on the hood. He makes head-turning, toe-tapping language combinations feel somehow inevitable. He is, in a word, virtuosic.

In the poems from Holding Company (2010), Roll Deep (2015), and The Absurd Man (2020), we see Jackson’s interests both expand and deepen. He combines the personal and political with often unexpected insights. “Going to Meet the Man” describes a standoff between the police and protestors as “a barricade of shields, helmets, batons, and pepper spray: / on the other, a cocktail of fire, all that is just and good.” In “Stand Your Ground” — written in a contemporary form called a golden shovel in which the end words are taken from another writer’s poem, in this case Brooks’ “Beverly Hills, Chicago” — he states his meaning even more directly: “America, I’ve had enough.” That is, Jackson is fed up with the racism still rampant more than a century after Brooks herself was born.

The final poem in Razzle Dazzle is called “Double Major,” implying that the poet also sees two versions of himself. A man with more pedestrian concerns — washing behind his ears and getting to bed at a reasonable hour — gently ribs the man who stares back at him in the mirror. That other Major “believes he can mend his wounds with poetry.” And there are worse beliefs.

Erica Wright is the author of four crime novels and two poetry collections. Her essay collection Snake was released in 2020. She grew up in Wartrace, Tennessee, and now lives in Knoxville.