It’s Not Even Past

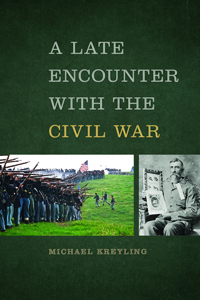

In A Late Encounter with the Civil War, Michael Kreyling continues his exploration of collective memory

“Robert Penn Warren claimed that differences in interpreting the Civil War are the American tradition,” writes Michael Kreyling in a statement that could serve as the thesis of A Late Encounter With the Civil War, his new collection of essays. The book examines a variety of sources both high and low that reveal the profound influence of the Civil War on American memory and culture. In the book Kreyling argues persuasively that—channeling Faulkner’s famous aphorism—“The past is never dead—it’s not even past.”

The three essays in A Late Encounter With the Civil War center on “the first two official commemorations of the War, its semicentennial and its centennial,” as well as the ongoing sesquicentennial. “We use personal and collective memory of the past to help us negotiate the present, to determine who we are by reminding ourselves of who we have been,” Kreyling writes. “And those who study both types of memory tell us that we are used by these negotiations as much as we use them.”

The three essays in A Late Encounter With the Civil War center on “the first two official commemorations of the War, its semicentennial and its centennial,” as well as the ongoing sesquicentennial. “We use personal and collective memory of the past to help us negotiate the present, to determine who we are by reminding ourselves of who we have been,” Kreyling writes. “And those who study both types of memory tell us that we are used by these negotiations as much as we use them.”

This brief, accessible work of literary scholarship continues the project Kreyling began in The South That Wasn’t There, a longer examination of the embattled memory of the Civil War, particularly in the collective minds of white Southerners who prefer the romanticized version of antebellum life memorialized in Gone With the Wind over the darker, grimmer history found in Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone. In his newest essays Kreyling widens his lens, focusing not just on Southern collective memory but on American cultural memory as a whole.

The first essay, “Remembering the Civil War in the Era of Race Suicide,” draws on sources from the time of the Civil War’s semicentennial, though some of them are completely unrelated to the war itself save for their powerful subtext, which Kreyling nimbly interprets in the context of Theodore Roosevelt’s campaign to promote “Americanism.” In addition to including the appropriate critique of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation as an example of a broader cultural turn against what Roosevelt called “the rising tide of color,” Kreyling goes a step further by characterizing the primary antagonist of The Great Gatsby, Tom Buchanan, as “a buffoonish caricature of Rough Rider Theodore Roosevelt” who “garbles the eugenicist credo that Roosevelt upheld as a matter of private and public privacy.” He reinforces this point through the famous Aryan rant Fitzgerald uses to characterize Buchanan in his first appearance in the novel: “This idea is that we’re Nordics,” Buchanan says.

“There are four adults in the room,” Kreyling points out, “and the only one whose racial provenance Tom is in doubt about is his wife, the southern girl from Louisville. His bluster confirms the widespread anxiety about race purity.” In pursuing the theme of race purity’s prevalence in American life outside the South, Kreyling doesn’t stop in Long Island: on the other side of the Atlantic, he discovers the same theme in the subtext of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and argues that the novel owes at least some of its popularity in the United States to its implicit advocacy of race purity and its expression of anxiety about the “corruption” of white blood by outsiders.

“There are four adults in the room,” Kreyling points out, “and the only one whose racial provenance Tom is in doubt about is his wife, the southern girl from Louisville. His bluster confirms the widespread anxiety about race purity.” In pursuing the theme of race purity’s prevalence in American life outside the South, Kreyling doesn’t stop in Long Island: on the other side of the Atlantic, he discovers the same theme in the subtext of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and argues that the novel owes at least some of its popularity in the United States to its implicit advocacy of race purity and its expression of anxiety about the “corruption” of white blood by outsiders.

Chapter two, “The Last Living Memory,” leaps forward to the years surrounding the Civil War centennial, “celebrated in the anxious atmosphere of the Cold War.” Here Kreyling turns back to that great sage of post-bellum Southern identity, Robert Penn Warren, who by 1960 had reformed his youthful pro-Dixie sentiments into an apologetic mode that left him better equipped to evaluate the war’s impact on both North and South: “The Southern Mind, Warren argued, was shaped by its great denial of the reality of slavery and its refusal to see defeat in the Civil War as connected to its labor economics and social structures. He labeled this cultural myth the Great Alibi.”

In contrast, the North remained afflicted by belief that a “Higher Law,” as Warren put it, “had conferred a monopoly of virtue on the advocates of Union and Abolition.” Thus, Kreyling writes, “southern denial and the northern claim to a higher law … worked together to abolish the pragmatic middle.” He concludes by discussing the 1965 film Major Dundee, which stars Charlton Heston and Richard Harris as a pair of former West Point classmates on opposite sides of the Civil War. In the film, North and South join forces to fight the “other” as embodied by a band of renegade Apaches whom Kreyling argues are meant to represent the “French misadventure in Vietnam that precipitated U.S. involvement there.”

As was the case in The South That Wasn’t There, Kreyling refuses to limit himself to canonical works in his exploration of collective memory, and he gets even more adventurous in the third essay, “The Civil War and its Afterlife,” in which he considers the revisionist fantasy of the short-lived comic-book series Captain Confederacy by Will Shetterly and Vince Stone. Kreyling has no problem discussing Captain Confederacy, Grant Comes East by Newt Gingrich and William R. Fortschen, and The Guns of the South by Harry Turtledove alongside more literary examples like Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and E.L. Doctorow’s The March. Indeed, one of the more appealing aspects of Kreyling’s scholarship is his willingness to embrace sometimes obscure, low-culture media as meaningful and resonant expressions of the anxieties underlying the broader territories of collective memory and identity.

To accept Kreyling’s thesis, of course, one must overcome the literary snob’s natural knee-jerk impulse to dismiss the comparison of an out-of-print comic book and a politician’s co-written fantasy novels to the likes of William Faulkner. Once this not-inconsiderable feat is achieved, the argument at the center of A Late Encounter With the Civil War grows increasingly persuasive. In the end, Kreyling seems to argue, all of these examples of Civil War representation are expressions of an argument that goes far beyond the smaller stakes of aesthetic or literary merit. The Civil War becomes a ground on which we have always contested and will continue to contest. As Kreyling writes of Doctorow’s The March, “The past was a whole lot like the present and therefore no refuge from the sorrows of now.”

Michael Kreyling will introduce the James Franco film version of William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying at Vanderbilt University’s Sarratt Cinema on March 13, 2014, at 7:30 p.m. Admission is free and open to the public.