Just What the Governor Ordered

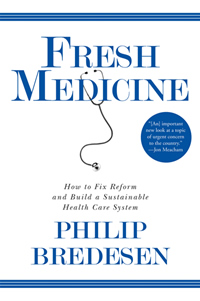

In a new book, Phil Bredesen weighs in on the health-care debate

Few American politicians are as well versed in the health-care debate as Tennessee Gov. Philip Bredesen. A former health-care executive, Bredesen came to office in 2002 promising to fix TennCare, the state’s Medicaid program, which was driving the state deep into debt. Bredesen spent much of his two terms in office bringing the program’s costs under control, a process that drew national headlines and talk of a cabinet position in the Obama White House.

Though the governor ended up staying in Nashville, he still has a lot to say about the landmark health-care bill that passed this spring. In Fresh Medicine: How to Fix Reform and Build a Sustainable Health Care System, Bredesen provides a searing but non-partisan critique of the bill, arguing that its major achievement, expanding coverage, is far outweighed by its failure to change the outdated, inefficient structures underlying the health-care crisis. While he admires his fellow Democrats’ motivations, he predicts that they are only digging a deeper fiscal hole by making health care less affordable in the long term. Recently, Chapter 16 got a chance to speak with him about the book.

Chapter 16: You’re leaving office early next year. What made you decide to write a book during your last few months as governor?

Bredesen: I’ve always admired how, in the early days of our republic, public officials would actually pick up a pen and try to set down some ideas at length, as opposed today’s obsession with sound bites and ghostwriters and such. I really care about this issue and I wanted to do the same.

Bredesen: I’ve always admired how, in the early days of our republic, public officials would actually pick up a pen and try to set down some ideas at length, as opposed today’s obsession with sound bites and ghostwriters and such. I really care about this issue and I wanted to do the same.

Chapter 16: The health-care act just turned six months old, and already you’ve got a book out criticizing it. Why did you feel the need to write this particular book right now?

Bredesen: I actually started it last year, with the idea of delivering it back in fall. I worked on it during September and October of last year, developing some of the ideas. Then when it became clear something might or might not happen in 2009, but was in any case well in the future, I talked with the publisher [Grove/Atlantic], and we said, “Let’s put it on ice”—because if I were to write a book before reform passed and then published the book afterward, everyone would look at it and say, “Doesn’t the governor read the newspaper?”

But why publish it now? I was disappointed with what they [Congress and the president] came up with. And I think it’s important that we not let all the energy go out of the subject, and that we continue talking about this. And I think a lot of people will agree. So I figured I’d go ahead and publish it and put it out there.

Chapter 16: One thing people will find interesting is that for you the insurance companies aren’t the bad guys. If there are bad guys, you see the problem lying elsewhere, and not with the insurance industry itself.

There are problems in the way we use insurance, but the insurance companies themselves aren’t the core problem. If we want to blame somebody, let’s look at other medical providers, like the pharmaceutical industry.

Bredesen: Insurance is a huge piece of the equation. And the insurance companies are no doubt about as good or greedy or competent or incompetent as any other industry sector. They certainly have done things that I don’t like, but that’s probably true of any industry we care to identify. But, while focusing on them and making them the enemy might be good political theater, we shouldn’t confuse political theater with reality. There are problems in the way we use insurance, but the insurance companies themselves aren’t the core problem. If we want to blame somebody, let’s look at other medical providers, like the pharmaceutical industry. In the book I use the example of [drug maker] Merck, where profits last year were equal to the earnings of all the companies in the Fortune 500 health insurance and managed-care category combined.

But, and I hope this comes through in the book, I don’t see this as an issue of enemies. Rather, it’s that we put a structure in place in the 1930s—an insurance-based, employer-based system—and it’s outgrown its usefulness. It’s obsolete. We’re sitting here in America with frequently inferior care which is more expensive than anywhere else in the world. You’re not going to fix that by simply adding more people to the rolls or singling out particular enemies.

Chapter 16: How did your background as a former healthcare-management executive and your efforts to reform TennCare, when you cut off thousands of Tennesseans to get costs under control, influence the ideas in the book?

Bredesen: All those experiences had their bearing, but I wouldn’t say any single thing was the prism through which I look at this stuff. The TennCare experience was very painful. It was somewhat politically painful for me—I had people sitting in my office twenty-four/seven for six months. But it was extraordinarily painful for the people who lost their health insurance because of it. What we were forced to do in the end was make reductions with a broadax rather than a scalpel. And it was very painful for the people who got lost in the cracks in that. The sense in the book that the system we have is not serving the needs of some of the people who most need it comes very strongly from that experience.

Bredesen: All those experiences had their bearing, but I wouldn’t say any single thing was the prism through which I look at this stuff. The TennCare experience was very painful. It was somewhat politically painful for me—I had people sitting in my office twenty-four/seven for six months. But it was extraordinarily painful for the people who lost their health insurance because of it. What we were forced to do in the end was make reductions with a broadax rather than a scalpel. And it was very painful for the people who got lost in the cracks in that. The sense in the book that the system we have is not serving the needs of some of the people who most need it comes very strongly from that experience.

The other thing that comes from my experience with TennCare is that if we indeed consider some level of health care a basic right, let’s divorce it from being charity handed out by politicians and organize ourselves deliberately and fairly and without anybody having to grovel to get it. I’d love to go back to more of what Harry Truman’s vision was, which is that there is some underlying level where everyone’s treated the same. We’ve really gotten close to that with Medicare, and there’s no reason we can’t do it with the rest of the system.

Chapter 16: You also lay a lot of blame on political partisanship, rather than liberal or conservative ideology.

Bredesen: What went wrong with the bill is that the White House turned it over to Congress. I practice the art of politics, and I understand that in the end there will be adjustments to reflect political realities. I may not happen to believe, for example, that tax credits are always an effective way to accomplish something, but I might well be willing to accept them in the end as a part of a compromise.

Fundamentally, I had hoped that the process would draw on the huge range of expertise we have across our country on this subject. Instead, the bill was basically crafted by staffers and advocacy groups, leaving behind ninety-nine percent of the richness of experience that would have been available. Legislative bodies have a role to play, but as editor more than author. It’s just naturally difficult in a body that large to come up with coherent strategies. I’ve always thought the role of the executive branch is to come up with plans, to draw on expertise, craft a proposal, and then let Congress do its editing work. There may be compromises, but that approach would have been a much stronger one.

Chapter 16: How will the way it passed affect the law now that it’s been enacted?

Bredesen: I think the way it was passed with a straight partisan-line vote is going to come back to haunt us big-time. The tension is not going to relax in the way it did with Social Security and Medicare. Medicare passed—it was contentious at the time, sure, but it was bipartisan—and once it was done, the tension subsided. But health reform is now firmly embedded in the world of partisan politics, and I assume Republicans will continue trying to alter or repeal it.

I also wish they had made it a broader bill; I wish they had made it something that really got at some of the underlying financial problems. I believe the costs associated with the bill will exceed the range we talked about during the debate very quickly. I don’t want to be a Cassandra, but we’re in a difficult financial situation in this country, and we’re going to have to deal with entitlements very soon. So let’s start addressing the issue now, particularly as related to health care, and not wait until China stops buying our bonds. Let’s start getting things set up so that when the whole issue comes to a head, we’ll be ready.

Chapter 16: So what would you do specifically? What’s the plan?

The core problem is this: if you leave health care as an open-ended entitlement, where the people providing services get to define how much service is provided and how much to charge for it, you will never contain costs.

Bredesen: The core problem is this: if you leave health care as an open-ended entitlement, where the people providing services get to define how much service is provided and how much to charge for it, you will never contain costs. The history of the last fifty years of health care is uniform in that regard. So let’s try to find a different way of doing it, one that disengages from the insurance model. That model is inefficient and it creates all sorts of bad incentives, ones where the incentive of any doctor or provider is to do more and charge more. Instead, let’s start by looking at systems of care like the Mayo Clinic, places that are admired today for the way they provide excellent care efficiently, and let’s build a national system around that.

To pay for it, let’s give people vouchers that can only be spent on health care. That’s essentially what Social Security is, just reworked for medical care. Of course, it’s different in the sense that if someone isn’t a part of the Social Security system, you’re willing to not write them a check—whereas if they’re not part of the medical system you’re not willing to let them die in the street. But if you disburse a limited amount of money and say it can only be spent on health care, then you’re limiting the maximum amount of money that comes into the market, which creates some competition and value. Then, third, you create quality auditing systems to monitor what is being provided. What the book is about is how to do all this in a fair and responsible way.

Chapter 16: One of the striking things about the book is how up-to-date it is—not only does it focus on a six-month-old policy, but you have references to things as recent as Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s dismissal as the head of operations in Afghanistan in June. How did you manage to write it so quickly, while still governor?

Bredesen: The ideas at the back of the book, about vouchers and limiting resources, that’s all stuff I thought about through the fall. Then, after reform passed, I spent evenings and weekends on it. I took time off for the Fourth of July and went to our place out West, where I locked myself in a room for a week.

I enjoyed the process immensely. I can still look at any page and think of something I’d like to add or alter. But I found that writing is a bit like painting. One of the challenges a painter has is knowing when it’s done, and it’s almost always done before you think it is.

Chapter 16: Does the fact that you wrote this book offer a hint about where you’ll go next?

Bredesen: It doesn’t in a forward-looking sense. I did this because I wanted to do it. Now, if there is some further discussion on the subject, I’d love to be a player in it in some way. But it’s not like I’m running for president and doing the obligatory self-congratulatory autobiography. I’ve already thought of a few other topics I’d like to write on, so maybe I’ll spend some time doing that. I hope to have plenty of time for a third career.