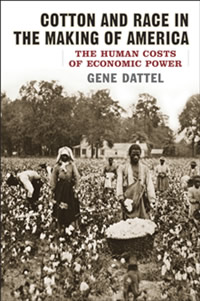

King Cotton and His Victims

Financial historian Gene Dattel looks at the human impact of the cotton trade

In America’s popular mythology about race, “King Cotton” is a critical but secondary character. The South’s cotton-based economy relied on the captive labor of blacks, whose enslavement continued in all but name in the decades after the Civil War. The North, with its more diverse, industrialized economy, supposedly had no stake in slavery. In Cotton and Race in the Making of America: The Human Costs of Economic Power, financial historian Gene Dattel, a graduate of Vanderbilt Law School and former managing director at Salomon Brothers and Morgan Stanley, sets aside this standard narrative of opposition between North and South, focusing instead on cotton’s critical importance to both regions. He literally follows the money, tracing the complexities of the cotton trade to show that there was a national interest in keeping blacks imprisoned in the fields. What he calls the “amoral” economics of cotton, along with ubiquitous white racism, created the enduring legacy of impoverishment and discrimination suffered by African Americans.

Dattel begins his analysis with the Constitutional Convention in 1787, where opposition to slavery was overwhelmed by a shared devotion to the sanctity of private property and, as Dattel puts it, “a desire for economic development that trumped almost all else.” Slavery, he argues, was “a nationwide business” at the time, with slave ships operating out of ports in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and Northern merchants doing a brisk trade with Southern slaveholders. The final draft of the Constitution, with its infamous three-fifths compromise and fugitive slave clause, offered “a rough, indirect, but ultimately lasting set of guidelines to regulate the commercial existence of slavery.” Early abolitionists comforted themselves with the belief that slaveholding would eventually become economically unviable—as it already had in many of the Northern states—and “wither away.”

Thanks to Eli Whitney and the British textile industry, however, slavery instead took on an importance the founding fathers never imagined. Southern cotton cultivation rose dramatically at the start of the nineteenth century, creating a corresponding growth in the number and value of slaves. Dattel traces the financing of the burgeoning cotton trade by Northern banks, as well as the migration of Northern whites into the cotton-growing states. “Nowhere was America’s material and speculative nature more evident than in the cotton South,” he writes. “Money poured in from the American North and Europe to purchase land and slaves.”

Thanks to Eli Whitney and the British textile industry, however, slavery instead took on an importance the founding fathers never imagined. Southern cotton cultivation rose dramatically at the start of the nineteenth century, creating a corresponding growth in the number and value of slaves. Dattel traces the financing of the burgeoning cotton trade by Northern banks, as well as the migration of Northern whites into the cotton-growing states. “Nowhere was America’s material and speculative nature more evident than in the cotton South,” he writes. “Money poured in from the American North and Europe to purchase land and slaves.”

Ironically, the very commodity that tied the regions together economically tore them apart politically. As the crisis over the expansion of slavery deepened, the economic clout of its cotton gave the South “the determined mind-set, the financial credit, and the fearsome gravitas” to believe it could secede. After the Civil War, cotton remained an “indispensable” commodity, and Dattel argues that any hope for real liberation of blacks was quashed by “America’s relentless commercial priorities.” The federal government, he writes, knew “that the crop would play a vital role in getting the nation back on its financial feet and in deciding what to do about the surrendered South.” Cotton, in other words, would pay for the war and promote reconciliation through a shared economic interest between North and South—and the cotton would be produced with black labor.

Explaining exactly how free blacks were kept effectively chained to the fields takes Dattel away from economics and into the murkier realm of culture and politics. With a motivation he describes as “far more nefarious than most historians are willing to acknowledge,” Reconstruction-era Republicans wanted freedmen kept in the Southern states and given the vote, in order to strengthen the party’s political power. More importantly, there was an overwhelming popular opposition in the Northern states to the migration of blacks, born of simple racism. Dattel documents the hostility blacks met whenever they attempted to settle outside the South, and offers ample proof that opposition to slavery was almost never synonymous with a belief in black equality. (For example, Dattel quotes Harvard historian Albert Bushnell Hart, who had a “sound abolitionist pedigree,” as saying that the average black man was a “moral and social cripple.”) The near-universal opinion that blacks were unfit for anything but menial labor combined with the demand for cotton workers, shut most doors for former slaves. “For white America,” Dattel writes, “all roads for blacks led back to cotton.”

Explaining exactly how free blacks were kept effectively chained to the fields takes Dattel away from economics and into the murkier realm of culture and politics. With a motivation he describes as “far more nefarious than most historians are willing to acknowledge,” Reconstruction-era Republicans wanted freedmen kept in the Southern states and given the vote, in order to strengthen the party’s political power. More importantly, there was an overwhelming popular opposition in the Northern states to the migration of blacks, born of simple racism. Dattel documents the hostility blacks met whenever they attempted to settle outside the South, and offers ample proof that opposition to slavery was almost never synonymous with a belief in black equality. (For example, Dattel quotes Harvard historian Albert Bushnell Hart, who had a “sound abolitionist pedigree,” as saying that the average black man was a “moral and social cripple.”) The near-universal opinion that blacks were unfit for anything but menial labor combined with the demand for cotton workers, shut most doors for former slaves. “For white America,” Dattel writes, “all roads for blacks led back to cotton.”

Just as their enslavement had been driven by commercial interests, blacks’ disappearance from the cotton fields was also a matter of economics. The development of the mechanical cotton picker and a steep decline in the demand for American cotton after 1930 erased the need for field workers. Industrial labor shortages “trumped prevailing white Northern racial animosity,” as Dattel puts it, and blacks finally began to leave the South in large numbers.

The legacy of their exploitation, however, has not been erased. The history of cotton provides a vivid illustration of what Dattel calls “the near fateful power of economics in human history.” The dire poverty of black communities in the Delta, where nothing has filled the gap cotton left behind, is the direct consequence of the nineteenth-century monoculture economy. Moreover, Dattel suggests that the long decades of literal and de facto slavery, along with lingering white racism, are responsible for the “seemingly permanent” urban black underclass in America. This classic liberal position cannot be dismissed as cliché, given that Dattel offers it in the wake of his meticulous account of white enrichment through the theft of black labor. “The quest for money determines what people do and why they do it,” he writes in the book’s introduction, and that hard-edged premise makes Dattel’s analysis—however uncomfortable—both fascinating and persuasive.