Laugh Lines

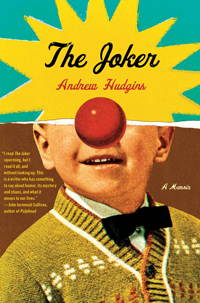

Poet Andrew Hudgins dives into the deep end of humor with his memoir, The Joker

Andrew Hudgins is a distinguished poet and scholar with a long list of publications and honors to his credit. He’s a member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers, and he’s been a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He’s also an inveterate—even compulsive—teller of jokes. Silly jokes, dirty jokes, gross jokes, outrageous jokes: he loves them all and loves to share them, in spite of the attendant risks he pondered in a recent op-ed for The New York Times.

In The Joker, Hudgins tells the story of his life through the jokes that marked its passages, from the first joke he encountered at age seven (“What’s black and white and red all over?”) to the one he hopes to enjoy in the afterlife. While there are plenty of laughs in the book, Hudgins is interested primarily in what’s behind and beyond the laughter. What do jokes do for us, and why do we love the ones we do? These are questions that arise again and again as Hudgins recounts his experiences growing up as a military brat in the 1950s and 60s and his adult struggles with love.

In The Joker, Hudgins tells the story of his life through the jokes that marked its passages, from the first joke he encountered at age seven (“What’s black and white and red all over?”) to the one he hopes to enjoy in the afterlife. While there are plenty of laughs in the book, Hudgins is interested primarily in what’s behind and beyond the laughter. What do jokes do for us, and why do we love the ones we do? These are questions that arise again and again as Hudgins recounts his experiences growing up as a military brat in the 1950s and 60s and his adult struggles with love.

He’s particularly interested in the realm where humor touches the ugly or troubling aspects of our psyches. A good chunk of The Joker is devoted to dissecting the racist jokes some of his white Southern family enjoyed. Recalling his own teenage fondness for dead-baby and Helen Keller jokes, he writes, “By laughing at cruelty and fate, you could pretend to be superior to it, and yet what fueled the laughter was the absurdity of laughing: nothing tames death. So you might as well laugh, brother, and strengthen your mind against your own vanishing.”

Hudgins is a professor of English at Ohio State University in Columbus, and he teaches poetry at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, which will be held this year July 23-August 4. In addition to The Joker, he has just released a new book of poems, A Clown at Midnight, from Mariner Books. He answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: You dissect a lot of jokes—good and bad—in The Joker, taking them apart to see how they work. Is there any feature that all good jokes share?

Hudgins: Surprise. The joke has to take us somewhere we didn’t expect to be, but the surprise has to make sense in the terms of the Möbius-strip logic of the poem. We have to understand how we get to the illogical place we end up at.

Dr. Pavlov is at home. The doorbell rings and Pavlov exclaims, “I forgot to feed the dogs!”

Dr. Pavlov is at home. The doorbell rings and Pavlov exclaims, “I forgot to feed the dogs!”

To someone who doesn’t know about Dr. Pavlov and his famous dogs, this joke makes no sense at all. Why would a doorbell remind you to feed the dogs? But at the moment we get the joke, we also realize the larger point: not only has Pavlov trained his dogs to salivate at the bell that marks their being fed, he’s also trained himself to associate the bell with feeding the dogs. We understand the total inversion of roles in an instant, and it both surprises us and resolves that surprise in an odd form of sense.

Chapter 16: There’s some pretty wrenching stuff about your early life in The Joker, and you give a lot of attention to the ugly side of humor, including the way racist jokes were used in your family. Were you ever tempted to write a softer book—one that didn’t go quite so deeply into difficult territory?

Hudgins: No. I don’t think there’d be any point to that book. I grew up with the ugly jokes and the milder ones told side by side. To understand humor, you have to think about both kinds, and also I felt like those racist jokes need to be pulled out and exposed to light, which is the ultimate disinfectant.

Chapter 16: Jokes bring a lot of pleasure and cause a lot of trouble. Is it possible to have the pleasure without the trouble? Must there always be “the human cost of laughter?”

Hudgins: I’m not sure. I’d hate to live in a world where all humor is like the anecdotes I grew up with in Reader’s Digest, which were mostly anodyne and only very occasionally funny. And I say that as someone who has scoured those pages for decades, looking for a laugh. But I also admire comedians like Bob Newhart and Bill Cosby and others who can work clean and be very funny. I think of Rita Rudner as a very funny and PG comedian.

But. But. But. Is it scatological humor if you say, “Before I met my husband, I’d never fallen in love, though I’d stepped in it a few times?” Yes, but not so much as to offend even a deacon on Sunday morning. But what about when Rudner tells us that she went to Morehead State University in Minnesota, and she realized that the supporters of the visiting team were looking at them funny when, during the game, they chanted “More Head! More Head!” I love that joke but I don’t think I’d tell it to the deacon who laughed at the joke about love.

Chapter 16: You’ve said that people are more cautious with the jokes they tell now via email and other digital media, for fear their words will come back to bite them. Is our reliance on electronic communication changing our jokes in other ways?

Chapter 16: You’ve said that people are more cautious with the jokes they tell now via email and other digital media, for fear their words will come back to bite them. Is our reliance on electronic communication changing our jokes in other ways?

Hudgins: Absolutely. More and more the jokes I get via mail are pictures or videos, and more and more of it is professionally produced instead of being a form of folk humor. I love it all, but I do miss the person-to-person calculations and adjustments you have to make when you are telling a joke to someone who is actually there.

Chapter 16: Is there any sense in which your jokes and your poems come from the same impulse?

Hudgins: Both poems and jokes value compression and precise phrasing. The poet Howard Nemerov liked to say that he likes writing humorous poems because when you read them to an audience you know immediately if they were successful. The audience either laughed or it didn’t.

Chapter 16: What would make you stop telling jokes?

Hudgins: If people stop laughing. Actually that might have stopped me when I was very young, but not now. Now the answer is “death.”

Chapter 16: Since Chapter 16 is all about Tennessee writers and literary events, any chance you’ve got a good Tennessee joke for us?

Hudgins: I’ll start with one that I saw attributed to the country rocker Steve Earle.

Q: What has twenty heads, forty legs, and three teeth?

A: The front row at the Grand Ole Opry.

It’s mean (and untrue of course), but it makes his point humorously and forcefully.

As I was growing up, one of the handful of books in the house was Tall Tales from the High Hills. Most of the stories were set in North Carolina, and instead of the more modern stories about stupid rednecks, these were tales in which the wily hill folk outsmart the condescending city slicker and the revenuer looking for their stills. But here’s one I like:

Ma says to Pa, “Cletus next door has started running a new batch of moonshine last night.”

Pa says, “How can you tell? I don’t smell nothing.”

“Me neither, but a bunch of mice from over that way just barged in here this morning and beat the crap out of our cat.”

Andrew Hudgins will read from his work on July 27, 2014, at 4:15 p.m. at the Bairnwick Women’s Center on the campus of The University of the South in Sewanee. The event, part of the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, is free and open to the public.