Let the Truth Show Itself in the Work

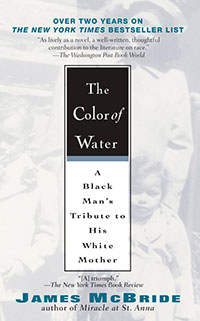

Chapter 16 talks with James McBride, author of the 2016 Nashville Reads selection, The Color of Water

Nearly twenty years have passed since the publication of James McBride’s first book, The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother. The book spent two years on the New York Times bestseller list and continues to be a regular selection in city-wide programs like Nashville Reads.

The enduring popularity of The Color of Water is easy to understand. It’s a story about race in America, written in a remarkable style which juxtaposes McBride’s own childhood memories with first-person accounts from his mother’s point of view. It’s also a remarkable story of survival, persistence, self-preservation, and self-discovery. Most of all, it’s a deeply moving, emotionally honest account of the love between mothers and their children.

The enduring popularity of The Color of Water is easy to understand. It’s a story about race in America, written in a remarkable style which juxtaposes McBride’s own childhood memories with first-person accounts from his mother’s point of view. It’s also a remarkable story of survival, persistence, self-preservation, and self-discovery. Most of all, it’s a deeply moving, emotionally honest account of the love between mothers and their children.

In his memoir and three subsequent novels—Miracle at Santa Anna (2002), a tense drama about African-American soldiers behind enemy lines during World War II, which was adapted for the screen by director Spike Lee; Song Yet Sung (2008), an antebellum drama inspired by the heroics of Harriet Tubman; and the National Book Award-winning The Good Lord Bird (2013), a tragicomic novel about a young boy who escapes slavery and teams up with John Brown in Kansas—McBride has proven himself to be a deft, incisive, altogether original writer who simultaneously provokes sharp criticism of the crimes of slavery and racism and tells universal stories about hope, love, and faith that can often be as funny as they are moving.

Despite rave reviews, The Good Lord Bird was an underdog for the 2013 National Book Award for Fiction, up against the likes of George Saunders, Jhumpa Lahiri, Rachel Kushner, and Thomas Pynchon. McBride was himself so convinced he stood no chance of winning that he was still eating when his name was called, and carried his dinner napkin to the podium with him to receive the honor. This is what the words of James McBride do, even to their own author: they sneak up on you.

Anyone who had read the book, however, couldn’t possibly have been surprised. With The Good Lord Bird, McBride explores a host of American archetypes and icons, retelling the story of John Brown in a tale that is at once devastating and raucously funny. A professional jazz musician, McBride understands how to make his words swing, shifting tones, bobbing and weaving in and out of a variety of settings and milieus, making a revealing story in which we can all see ourselves reflected through the words and experiences of a cross-dressing runaway slave called Onion.

Anyone who had read the book, however, couldn’t possibly have been surprised. With The Good Lord Bird, McBride explores a host of American archetypes and icons, retelling the story of John Brown in a tale that is at once devastating and raucously funny. A professional jazz musician, McBride understands how to make his words swing, shifting tones, bobbing and weaving in and out of a variety of settings and milieus, making a revealing story in which we can all see ourselves reflected through the words and experiences of a cross-dressing runaway slave called Onion.

Appropriately, McBride’s most recent book is a musician’s appreciation of perhaps the greatest performer in the history of popular music: the great James Brown, a subject as mercurial and complicated as any of McBride’s previous muses. The book is called Kill ‘Em and Leave, and one gets the sense that McBride has taken a few cues from the Godfather’s philosophy of performance. His books hit hard and fast, and his words are sharp and economical. As an interview subject, McBride acquits himself in similar fashion: he is quick, canny, incisive, and unflappable. In anticipation of his visit to Nashville, McBride answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: We’re coming up on the twentieth anniversary of the publication of The Color of Water. How surreal is it to have such a personal story become not just a big bestseller but a classic of its genre, too, read and taught in schools and widely adapted for programs like Nashville Reads?

James McBride: A dream come true. Had I known how many people were going to read that book, I’d have written a better book.

Chapter 16: Perhaps the most striking feature of The Color of Water is the point of view, in which you alternate from your own perspective to your mother’s. When you look at it now, after so much time has passed, do you ever feel as if she’s speaking to you?

James McBride: I haven’t looked at it in years. My mother lives in my heart now. She’s in God’s hands, and I hope to see her again someday.

Chapter 16: Your last novel, The Good Lord Bird, examines the story of John Brown through the eyes of a young cross-dressing escaped slave. In the few years since its publication, some of the issues that book raises (institutionally supported racism and violence against African-Americans, gender identity, etc.) have resurfaced in profound and disturbing ways. In first looking at the story of John Brown, did you have any sense that the powder-kegs were about to explode again?

Chapter 16: Your last novel, The Good Lord Bird, examines the story of John Brown through the eyes of a young cross-dressing escaped slave. In the few years since its publication, some of the issues that book raises (institutionally supported racism and violence against African-Americans, gender identity, etc.) have resurfaced in profound and disturbing ways. In first looking at the story of John Brown, did you have any sense that the powder-kegs were about to explode again?

McBride: No idea. If you try to write a novel around current events, you’ll be like the third monkey trying to get on Noah’s Ark. Better to frame your story around your own sense of self and morality. Let your thirst for good drive it.

Chapter 16: Your new book, Kill ‘Em and Leave, examines the life and career of James Brown. There are quite a few books about the Godfather out there, including one pretty recent “definitive” biography by music journalist R.J. Smith. What led you to take up James Brown as a subject, and what fresh perspectives were you hoping to bring to his story?

McBride: I just tried to tell it in a fresh way, from a musician’s perspective.

Chapter 16: In his recent New York Times review of Kill ‘Em and Leave, novelist Rick Moody begins by stating that “It’s an undeniable truth that when African-American writers write about African-American musicians, there are penetrating insights and varieties of context that are otherwise lost to the nonblack music aficionados of the world, no matter how broad the appeal of the musician under scrutiny.” Moody clearly means this statement positively, but it has ignited a small degree of controversy. How do you respond to the suggestion from a white writer that your book’s authority derives primarily from your blackness?

McBride: I have not read a book review in years, so I didn’t read Rick Moody’s review. But I’m glad he wrote it, and I’m thankful to him. He’s deeply talented. As for my “blackness” making me an authority, I don’t engage in that kind of talk too much. Too often it feels like one of those 2 a.m. college bull sessions where at the end somebody’s hoping to get laid. Art is for everyone. Let the truth show itself in the work.

Chapter 16: When I first read The Good Lord Bird, it occurred to me that you had written both an homage to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and a rebuke of it, inverting and subverting its plot and themes through role reversal; the novel is both reverent and wildly subversive. Did you intend engage this particular ur-text of American literature so directly?

McBride: Heck no. I’m not smart enough. I just wanted to write a good book. If I intellectualized too much about my work, I wouldn’t be able to get characters to move from one room to the next.

Chapter 16: You are a musician as well as a writer. Does being one ever help in being the other?

McBride: Sometimes, but I get tired of both. But it’s all I can do. I once tried rebuilding my old Volvo. I punctured the head while putting in a water pump. That ended my career as a mechanic.

Chapter 16: What do you think your mother would say about the fact that her life story—and her voice—have become a part of the contemporary canon of American literature?

McBride: I think she’d feel humbled. She felt there were mothers who sacrificed more, and did more for their kids, than she did. She loved her kids and did the job. I think she’d be happy her story helps others like her. Thankfully, there are millions like her. That thought helps me out of bed every morning.

[This article appeared originally on May 2, 2016.]

Ed Tarkington holds a B.A. from Furman University, an M.A. from the University of Virginia, and a Ph.D. from the creative-writing program at Florida State University. His debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.