Let This Homeplace Speak

An award-winning poet reflects on nature, violence, and personal histories

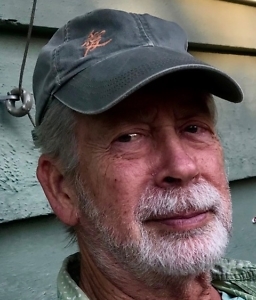

Richard Tillinghast is a patient poet. He wades into the water — or the night — and waits to be forgotten. What can be understood in such stillness? Now writing in his 80s, it’s tempting to think of this superpower as something that comes with age, but it seems more like a natural-born trait. His poem “A House in the Country” begins with the line “As a child I played at being invisible.” Many years later, Tillinghast is no longer playing, but adept at disappearance, of pausing long enough for the unknown to arrive. His latest collection, Blue If Only I Could Tell You, is a masterclass in reflection.

Fundamentally, Blue If Only I Could Tell You is about making sense of place — where Tillinghast was raised, where he lives now, and where he stopped along the way. His respect for different locations and the people of those locations is immense. In “Revival,” he writes,

Fundamentally, Blue If Only I Could Tell You is about making sense of place — where Tillinghast was raised, where he lives now, and where he stopped along the way. His respect for different locations and the people of those locations is immense. In “Revival,” he writes,

But let this homeplace speak. Let it tell its story

now that the machinery of the world

starts to misfire,

stall out, and begin its slow deceleration.

He is writing about an abandoned pickup truck, but also about a return to nature. Not simpler times, though. Tillinghast remains aware of his often privileged perspective, particularly in his poems about growing up in Memphis. He recalls driving home drunk once with his lights off, and a friendly police officer escorting him. He explains, “I was doing nothing dangerous / like going for a burger, or driving while Black.” It’s an unexpected turn for what begins as a humorous anecdote, a stark reminder that even something as tangible as a place is not the same for everybody.

Of the many locations evoked in this book, Tillinghast draws on his years in Ireland and includes a W.B. Yeats epigraph to open the first section: “One thing I did not foresee…the growing murderousness of the world.” Yeats was responding to the Easter Rebellion of 1916, an armed Irish uprising against British rule, which led to nearly 500 military and civilian deaths. We often see Tillinghast’s dismay over the world’s violence, as well. In “Mimbreño,” he recounts Apaches being killed by U.S. soldiers: “The men were cut to pieces — / limbs, brains, chunks of bone.” Tillinghast’s gaze is unflinching.

Of the many locations evoked in this book, Tillinghast draws on his years in Ireland and includes a W.B. Yeats epigraph to open the first section: “One thing I did not foresee…the growing murderousness of the world.” Yeats was responding to the Easter Rebellion of 1916, an armed Irish uprising against British rule, which led to nearly 500 military and civilian deaths. We often see Tillinghast’s dismay over the world’s violence, as well. In “Mimbreño,” he recounts Apaches being killed by U.S. soldiers: “The men were cut to pieces — / limbs, brains, chunks of bone.” Tillinghast’s gaze is unflinching.

A different Yeats quotation comes to mind when reading Tillinghast’s latest collection. In The Celtic Twilight: Faerie and Folklore, Yeats writes, “We can make our minds so like still water that beings gather about us that they may see, it may be, their own images, and so live for a moment with a clearer, perhaps even with a fiercer life because of our quiet.” This double whammy of clarity and fierceness is present throughout Blue If Only I Could Tell You. In a poem that draws parallels between the 19th-century smallpox and current coronavirus pandemics, we see a coffin factory with such high demand that its lights and saws are on all night. In an early poem about capturing a wild boar, Tillinghast wonders about a baby goat witnessing the struggle. “Nobody has instructed them yet,” he states, “about borders and killings and rage.”

The title poem is an homage not to Yeats but to García Lorca, an ode to the color blue in natural, historic, and artistic contexts. Tillinghast addresses blue directly, asking, “Is it hard sometimes to know just who you are?” It’s a question for the reader and the poet also of course, a moment to pause. Nearly every poem in this collection poses a question, sometimes several. There’s a unique comfort in the possibility of an answer rather than the answer itself.

It’s no wonder that Blue If Only I Could Tell You won the White Pine Press Poetry Prize. This is one of many accolades in Tillinghast’s distinguished career. He is the author of 13 poetry collections as well as 5 nonfiction books and has received a host of prizes and grants, including one from the Guggenheim Foundation and another from the National Endowment for the Arts. He grew up in Memphis and currently lives most of the year in Hawaii, though he can be spotted in Sewanee during the summer months.

As he writes in “A Way Station in the Punjab,” Tillinghast has created “a place […] to make sense of my travels.” It’s tempting to think of those travels literally with the poet’s many trips and stays in mind, but there’s a traveling of the mind, as well. These poems are rich in contemplation, a satisfying glimpse of Tillinghast’s decades as an astute observer.

Erica Wright is the author of four crime novels and two poetry collections. Her essay collection Snake was released in 2020. She grew up in Wartrace, Tennessee, and received her M.F.A. from Columbia University.