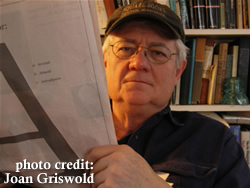

Lexicon Man

Humorist Roy Blount Jr.’s second stab at the dictionary confirms him master of all words

Some books beg not to be read from beginning to end. They invite jumping around, fifty pages forward, twenty pages back, in a mad scramble that leaves the reader delighted but uncertain what has been missed. Like its 2008 predecessor, Alphabet Juice, Alphabetter Juice: or, The Joy of Text, by Vanderbilt graduate Roy Blount Jr., is a collection of entries ranging from a few words to a few pages in length, ordered alphabetically, each of them funny enough to launch a scavenger hunt across the text in search of more. The reader is like a prospector who stumbles into a field with gold nuggets just lying on the ground—it’s hard not to run around greedily, snatching them up without rhyme or reason. (Well, there is some rhyme, in the form of three comic poems on eating shellfish, which appear under the entry for “crustaceous.”)

A few shorter entries are simply instructive as to usage, such as this universally applicable advice on “prior to,” printed here in its entirety: “There is no need for this phrase. It reeks of soulless organization. Before is what people say.” But most entries delve deeper into word origins and usages, with surprising asides, such as this one on “prick”: “Did you know that prick in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, according to OED, was ‘a term of endearment for a man: darling, sweetheart’? From a colloquy by Erasmus as translated in 1671: ‘Ah, ha! are we not alone, my prick? … Let us go together to my inner bed-chamber.’ (This is not Erasmus speaking to himself, so to speak. It’s a likeable strumpet, Lucretia, addressing a friend and former customer, Sophronious, who, having reformed himself, proceeds to talk her into leaving her lewd ways. In another translation she calls him ‘cocky.’ I always wanted to read me some Erasmus. I’m going to find a good modern translation.)” This is followed by the history of prick’s evolution to its modern meaning.

In his introduction, Blount promises, “This book includes two disastrous wedding nights, several touches of romance (aside from the long-deferred union of scratch and itch), and lots of animal life (eels, crabs, elephants, flies), but it all springs from things going on among letters on a printed page.” Thus, even before finishing the introduction, the reader may be thumbing through pages for eels (their cut-up bits may wriggle after death) or flies (shouldn’t it be called a “pester,” Blount asks). And then the introduction is never finished, because the reader has already begun grabbing nuggets.

In his introduction, Blount promises, “This book includes two disastrous wedding nights, several touches of romance (aside from the long-deferred union of scratch and itch), and lots of animal life (eels, crabs, elephants, flies), but it all springs from things going on among letters on a printed page.” Thus, even before finishing the introduction, the reader may be thumbing through pages for eels (their cut-up bits may wriggle after death) or flies (shouldn’t it be called a “pester,” Blount asks). And then the introduction is never finished, because the reader has already begun grabbing nuggets.

While most entries, like the one for “succinct,” for example, wander around for several paragraphs and may or may not get to the nitty-gritty (another page-long entry that tells a story) of the word to which the entry is devoted, nearly all of them cause a reader to laugh out loud, to become devoted to the entries, and the very funny man who created them.

[This review appeared originally on June 27, 2011.]

Roy Blount Jr. will discuss and sign copies of Alphabetter Juice at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13. All festival events are free and open to the public. To read Chapter 16’s interview with Blount about Alphabet Juice, click here.