Life and Love on “The Rock”

Our visit to Alcatraz opened my eyes and heart

Our lives are full of images we wish we could unsee, whether childhood traumas or the terrible accident on the way home from work. Or a notorious American prison, closed for 60 years. Last summer when I told my neighbor I wasn’t interested in seeing Alcatraz on my trip to San Francisco, she said, “Oh, you must go. It’s a bird sanctuary, and gardens flourish in the ruins of the prison.”

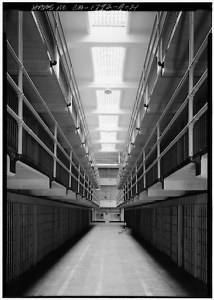

So without knowing anything other than the names of its most famous criminals — Al Capone, Machine Gun Kelly, and Robert Stroud, the “Birdman of Alcatraz” — I boarded a ferry, aptly named Solitary, with my daughter and her family at Pier 33 for the island, now managed by the National Park Service (NPS). I don’t know what I expected to see at the site, first a military, then federal prison, but there were gulls, cormorants, guillemots, and night-herons on the steep cliffs whitewashed by their excrement, and even some fluffy babies — though trails to fuller views on the old parade grounds were closed for the nesting season. We saw lush gardens beaten in the winds off the bitter Pacific, long ago planted and tended by officers’ families and prisoners: roses, fig trees, succulents, fuchsia, hawthorn, poppies.

I shivered peering into the tiny cells, imagining their damp cold; amateurish paintings and accordions to pass the sameness of time; the cafeteria as the most dangerous space on the compound. The worn structures jutted bleak and haunted from the rock island, and I thought how those lives must have degraded year after year, some mentally ill who now would have been treated in ways other than deprivation or solitary confinement.

Sometimes our traumas are so enormous and deeply embedded that, in self-preservation, we turn away from the worst of the world’s splinters. Just as I did in younger days, the baggage of my mother’s bipolar illness weighing me down — tongue-tied when two high school friends lost their mothers and, later, avoiding the workmate whose son committed suicide, the acquaintance who had a mastectomy. Not knowing what to say or how to empathize, how to embrace their grief when I was still puzzling out my own. We’ve all been there, guarded in our armored shells, imprisoned on our personal island. Tending our own gardens, literally and metaphorically.

Nonetheless, I’m drawn to those who are familiar with their grief. Like orphans, like moths to the flame, we recognize each other. Our parents’ divorce, our own. Our dark memories, our brokenness. We tell ourselves that, somehow, by melding these mutual hurts, we can mend the estrangements, we can sprint on in life’s three-legged race as one, wholeheartedly. But do we? Do we really sprint on as one — or continue to limp inside, the fracture unhealed?

My daughter didn’t go to Alcatraz willingly. She grumbled the whole way, punctuating the morning with sarcasm: “Yay, it’s prison day!” Perhaps she was right — what purpose did it serve to see this horrific chapter of history? To its credit, the NPS dedicates part of the tour to the racial and mental health injustices of the country’s entire prison system, which included Alcatraz, closed in 1963. Our visit there opened my eyes, and I hope my heart a little more, not only to the ravages of history, but as a caution, a reminder to turn toward suffering, both within and without — and not look away. To not harden myself to reaching out and exposing my own wounds, to not bar myself in a comfy cell of my own making.

I’m learning to take in those things I once wanted to unsee. I’m learning that we must first mend the ragged pieces of ourselves before we can bring that self wholly to others. I’m learning to continue praying for the unconscious man on the roadside, as well as the one pumping his chest in CPR after the accident. To send my energies and comforts out and out, as well as my actions for change and justice. The wild gardens on Alcatraz are called survivor plants. A fitting term for what they have witnessed and borne in the wind-whipped decades. Fitting for what we all witness and bear in our own weathered years and still shoulder willingly, the burdens shared with others, whether hugs or casseroles.

As we waited to queue onto the ferry for the mainland, my oldest granddaughter looked up and pointed — above us a love letter in the sky, puffy and cloudlike: ❤ momo ❤ Whoever or whatever “momo” was, it was surrounded by hearts, by love, broadcast for all to see. Even there, on “The Rock,” as inmates called Alcatraz. Even in a place that called us to look hard and long at the blackest recesses of humanity before turning back to the bright bay as the fog lifted, glinting with white caps and sun.

Poet, playwright, essayist, and editor, Linda Parsons is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and the copy editor for Chapter 16. Her sixth poetry collection, Valediction, is forthcoming in June 2023. Five of her plays have been produced by Flying Anvil Theatre in Knoxville, Tennessee. She is an eighth-generation Tennessean.