Life is Not a Bard’s Song

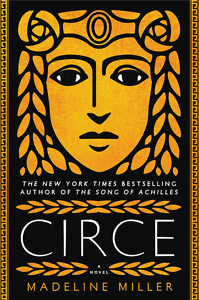

Madeline Miller reframes and retells the story of Homer’s Circe

Madeline Miller’s debut novel, The Song of Achilles, was an imaginative, addictive riff on the passionate love story between Achilles, “best of the Achaeans,” and Patroclus, his tentmate and beloved companion-a love story that lies at the heart of Homer’s Iliad, the greatest war epic in the Western canon. The Song of Achilles was a New York Times bestseller that also won the prestigious Orange Prize. Critics praised Miller’s uncanny ability to shine new light on a story we thought we already knew.

Now Miller is back with Circe, another brilliant revamp of tales and characters drawn from Homeric poetry. The protagonist this time is a woman-or, rather, a goddess-whose minor role in the Odyssey serves as Miller’s jumping-off point. In Miller’s version of the story, old myths are shaken up, reframed, and expertly, intriguingly harrowed.

Homer introduces Circe in Book 10 of the Odyssey. After losing ships to the Cyclops and the Laestrygonians, Odysseus and his weary men ease into the harbor of an island called Aiaia, where they come across a goddess singing at her loom. Surrounded by tame wolves and lions, she invites them inside, serves them a feast, and then turns them-for no reason other than cruelty, as Homer tells it-into swine.

Miller begins her tale with Circe’s birth. “When I was born, the name for what I was did not exist,” she says, setting the stage right away for what will turn out to be a kind of Bronze Age ugly-duckling story: Circe, daughter of Helios, grows up an outcast among the Titans and nymphs she must call kin.

Circe is bullied relentlessly by her divine family. She has an affinity for mortals and a tricky way with herbs, and both tendencies get her in trouble with her forebears, who eventually banish her to Aiaia. Mortals and Olympians occasionally visit-the story would be short if they did not-and Miller weaves familiar characters (Hermes, Daedalus, Prometheus, Medea, and so on) into the fabric of Circe’s tale, with sometimes startling results.

In this story, men come off looking better than the gods and goddesses, who reveal themselves to be vain, shallow, capricious, amoral, and cruel. But the mortal sailors who wash up on Aiaia’s shore are far from perfect. In a searing and perfectly rendered scene, Miller flips convention on its head by showing us just why Circe transforms her male visitors into pigs. (Turns out they totally deserve it.)

Still, the book doesn’t really get going till Odysseus, Homer’s man of many twists and turns, arrives on the island. In The Song of Achilles, Odysseus is a secondary character who steals every scene. In Circe, he finally takes center stage. “Later, years later, I would hear a song made of our meeting,” Circe tells us. “I was not surprised by the portrait of myself: the proud witch undone before the hero’s sword, kneeling and begging for mercy. Humbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets. As if there can be no story unless we crawl and weep.”

Still, the book doesn’t really get going till Odysseus, Homer’s man of many twists and turns, arrives on the island. In The Song of Achilles, Odysseus is a secondary character who steals every scene. In Circe, he finally takes center stage. “Later, years later, I would hear a song made of our meeting,” Circe tells us. “I was not surprised by the portrait of myself: the proud witch undone before the hero’s sword, kneeling and begging for mercy. Humbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets. As if there can be no story unless we crawl and weep.”

Miller is far too canny to succumb to epic conventions, and the portrait she paints of Odysseus’s year-long sojourn in Circe’s halls, and in her bed, is nuanced, fascinating, and-frankly-hot. But Miller does not end Circe’s tale where Homer does. There was once a third epic of the Trojan War, which took up where the Odyssey leaves off: the Telegony (named for Telegonus, the son Circe bears Odysseus after he departs for Ithaka). Only two lines and a summary of the Telegony have survived, but Miller makes fascinating use of this scant material.

Circe, whom Miller has endowed with both the powers of a goddess and the emotional depth of a mortal, is beautifully humanized by her ferocious love for her son, who grows up, as most children do, to rage against a mother who wants only to keep him close to her and safe. “The Fates were laughing at me,” Circe miserably acknowledges when her maternal scheming ultimately fails. “It was their favorite bitter joke: those who fight against prophecy only draw it more tightly around their throats.”

The novel’s conclusion will certainly surprise modern readers. It may even shock them, but Miller is only following the outlines of the Telegony, so far as they are known. It would not do to give away the rest of the story; suffice it to say that even though Circe remains firm in her conviction that “life is not a bard’s song,” the end of Circe-which comes full circle, as all good stories eventually do-feels as satisfying and true as myth, or song, or even epic poetry.

Fernanda Moore has been a contributing writer to Chapter 16 since 2009. From 2013 to 2016, she was the fiction critic for Commentary; her work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Marie Claire, New York, and Southern Living, among others.