Like a Sculptor

Amy Hoffman talks with Chapter 16 about her memoirs, Lies About My Family, An Army of Ex-Lovers, and Hospital Time

Amy Hoffman has two families: the one she was born into, and the one she’s chosen along the way. Her memoirs tell both family histories with humor, honesty, and tenderness.

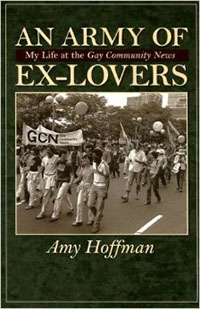

In her first book, Hospital Time, Hoffman testifies about caring for a friend who would eventually die of AIDS, as well as the sociopolitical climate of the Boston gay and lesbian community during the epidemic. An Army of Ex-Lovers, her second book, describes life at Boston’s Gay Community News, where, during the 1970s, she worked and gathered her chosen family. Her most recent memoir, Lies About My Family, brings us back to her roots in suburban New Jersey, weaving her own story of growing up Jewish and lesbian with her birth family’s stories of immigration, enterprise, and life-making.

In her first book, Hospital Time, Hoffman testifies about caring for a friend who would eventually die of AIDS, as well as the sociopolitical climate of the Boston gay and lesbian community during the epidemic. An Army of Ex-Lovers, her second book, describes life at Boston’s Gay Community News, where, during the 1970s, she worked and gathered her chosen family. Her most recent memoir, Lies About My Family, brings us back to her roots in suburban New Jersey, weaving her own story of growing up Jewish and lesbian with her birth family’s stories of immigration, enterprise, and life-making.

Hoffman now serves as editor of the Women’s Review of Books and teaches at Pine Manor College. Before her appearance at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, she recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: In Hospital Time, you recount the complex emotions that arise around your role as caregiver and literary executor for your friend Mike Riegle. How has that powerful book traveled with you throughout the years—that is, has your relationship to the subject matter, or the book itself, changed?

Amy Hoffman: The answer, of course, is Yes. I began writing the book more than twenty years ago, shortly after Mike’s death. The AIDS epidemic among gay men in the U.S. was at its height, and although even then some people were predicting that AIDS would eventually become a chronic condition, like diabetes, that could be controlled at least to an extent by drugs, that seemed like a utopian dream. I remember asking Larry Kessler, then executive director of Boston’s AIDS Action Committee, to blurb the book, and he wrote, among other things, that it captured a moment in history. I didn’t understand that—in the midst of the crisis, I couldn’t see the “moment” as something that would pass, or change—but he turned out to be exactly right.

Amy Hoffman: The answer, of course, is Yes. I began writing the book more than twenty years ago, shortly after Mike’s death. The AIDS epidemic among gay men in the U.S. was at its height, and although even then some people were predicting that AIDS would eventually become a chronic condition, like diabetes, that could be controlled at least to an extent by drugs, that seemed like a utopian dream. I remember asking Larry Kessler, then executive director of Boston’s AIDS Action Committee, to blurb the book, and he wrote, among other things, that it captured a moment in history. I didn’t understand that—in the midst of the crisis, I couldn’t see the “moment” as something that would pass, or change—but he turned out to be exactly right.

Now at least in this country effective treatments are available, and I have friends who have been living with the disease for years; it’s become more difficult than ever to explain the enormity of the crisis, the devastation, the grief, to people who didn’t experience it. I guess that’s not surprising, given that politicians, the media, the medical system, and families were so slow and reluctant to acknowledge the epidemic even when it was at its height. Memories have faded quickly.

I may still be angry about AIDS—but I’m less angry at Mike personally. At the end of the book I wrote about how I refused to say kaddish for him—the Jewish prayer for the dead, which isn’t about the dead at all but about the greatness of God and the wonder of the universe. I was not and am not a believer, but I have said kaddish for Mike. I’ve tried to deepen my compassion for him. I miss him. I still “see” him—see a thin, loping person in a baseball cap out of the corner of my eye. I like to imagine how he’d react to developments in today’s world. I mean, when Mike was office manager at Gay Community News he refused to process credit cards; how he would have hated, hated smart phones (although he might have liked grindr—he was a bundle of contradictions, like everyone).

Chapter 16: An Army of Ex-Lovers chronicles your participation in Gay Community News. Now you edit Women’s Review of Books. How do these experiences compare?

Hoffman: It’s almost funny to think of the two experiences together, since they are different in so many ways—most obviously in terms of resources. Women’s Review of Books is based at the eminently respectable Wellesley Centers for Women (WCW), at Wellesley College. And even though WCW is a “soft money” research center, in which every project must be self-supporting, and Women’s Review of Books barely manages this, my situation here is luxurious compared to GCN: working phones; steady, reasonable salary; office supplies. Our bills are paid up.

There are just so many things I can take for granted. WRB’s publisher, Old City Publishing, handles subscriptions, advertising, and production, whereas at GCN volunteers came in on Friday nights to stuff envelopes, sort subscriptions, and take them to the post office. Other volunteers came in on Thursdays to proof and lay out the paper, and take it to the printer. All this work had to be done physically (instead of by computer, as much of it is done now), and supervised by the staff.

Also, the reason we were messing around with all those envelopes is that our subscribers could not safely receive an LGBT publication that wasn’t in an opaque envelope. WRB goes into the mail unsealed. Women’s Review of Books is not a target of homophobic violence: no one shoots out our windows, fills our door locks with glue, or burns down our office.

At Women’s Review of Books, I’m the only editorial staffer; I work alone, and even though we invite comments on our blog, WOMEN=BOOKS, and letters to the editor in our journal, we don’t often hear directly from our readers. At GCN, I worked in a collective that was like a squabbling family: even today, the people I’m closest to are people I met there, and I’ve probably never felt angrier than I did at colleagues there. We were in constant communication with our readers and supporters: they visited and called the office, volunteered, donated money and services, and flooded us with letters.

At Women’s Review of Books, I’m the only editorial staffer; I work alone, and even though we invite comments on our blog, WOMEN=BOOKS, and letters to the editor in our journal, we don’t often hear directly from our readers. At GCN, I worked in a collective that was like a squabbling family: even today, the people I’m closest to are people I met there, and I’ve probably never felt angrier than I did at colleagues there. We were in constant communication with our readers and supporters: they visited and called the office, volunteered, donated money and services, and flooded us with letters.

I loved GCN; I love Women’s Review of Books, where I spend my days tinkering with text, interacting with writers, and looking at books. I hope that through my work here I’m making a contribution to women’s studies and the women’s movement by spreading the news about important new ideas and creative work. Maybe the difference is that at GCN I didn’t “hope”; I knew.

Chapter 16: What has been the difference, for you, between writing about your birth family (Lies About My Family) and writing about your chosen family (An Army of Ex-Lovers, Hospital Time)?

Hoffman: Urvashi Vaid wrote a foreword to Hospital Time in which she attacked the heterosexual family for rejecting and abandoning its LGBT members—and many of the readers of my book (including a sibling or two) objected to her critique. I shared it. At the time I wrote it (and during the period covered in An Army of Ex-Lovers), I was pretty alienated from my biological family: my parents had a hard time understanding my lesbianism and accepting my political activism; my siblings, with the exception of one of my sisters, rarely expressed support. At the same time, I was experiencing the deepening of the relationships among my own queer family, as well as seeing and participating in the love and day-to-day service people in the LGBT community gave to each other.

It was much more difficult to write about my birth family. My relationships with them—and with my family history—were so much more fraught and ambivalent. In both cases, though, I think the writing made me feel closer to my families, queer and straight—clearer about my relationships, more appreciative, more understanding.

Chapter 16: Do you feel you participate in a queer lineage of memoir with, say, Audre Lorde, or do you see your work as part of some other literary heritage?

Hoffman: Certainly Audre Lorde’s Zami is groundbreaking in terms of creating a “queer lineage of memoir”—as well as of modern memoir generally—because of its openly queer content and its discussions of race and class, but also because of its self-consciousness about the process of memoir. Lorde calls the book a “biomythography,” and by this I think she means that she in no way plans to be comprehensive about the events of her life (and in fact she leaves out many major episodes, including her marriage and other significant relationships); rather, she is narrating her journey toward wholeness and identity.

Actually, the writer I’ve found most inspiring in terms of thinking about memoir is Maxine Hong Kingston, whose books The Woman Warrior and Chinamen include conversations, dreams, folk tales, lists of laws and dates, imagined scenes—any means she can find to tell her story of a generational and geographical and personal journey. So, yes, I’m trying to work in the tradition of Lorde and Kingston.

Chapter 16: Personal narrative and testimony seem to hold a special weight in the queer and feminist communities. How have your identities influenced your decision to tell your own story, as well as that of your community?

Hoffman: I don’t think I’ve ever been to a meeting in the LGBT community where someone didn’t get up to testify—to tell what’s usually a story of struggle and suffering, relevant or not. And people usually listen respectfully and even offer advice and aid. I think it’s because even now there are so few places to tell our stories and to be truly heard and understood. LGBT history and experience have been hidden underground and despised; we’ve created codes, words and turns of phrase and gestures, to talk to one another—nuances that will be missed by hostile outsiders. It’s been a political act since the beginning of our movement to insist on our reality and worthiness: to reveal, unbury, bring into the light. Come out.

Hoffman: I don’t think I’ve ever been to a meeting in the LGBT community where someone didn’t get up to testify—to tell what’s usually a story of struggle and suffering, relevant or not. And people usually listen respectfully and even offer advice and aid. I think it’s because even now there are so few places to tell our stories and to be truly heard and understood. LGBT history and experience have been hidden underground and despised; we’ve created codes, words and turns of phrase and gestures, to talk to one another—nuances that will be missed by hostile outsiders. It’s been a political act since the beginning of our movement to insist on our reality and worthiness: to reveal, unbury, bring into the light. Come out.

Humans are social animals; we literally cannot survive in isolation (despite what Republicans maintain). As the South Africans put it, ubuntu: I am because you are. I think this is why being ignored and unseen is so deeply disturbing. Without the affirmation of others, it’s as though we don’t exist. Politically, as a lesbian, and personally, as one of six siblings in a busy and talkative Jewish family, I feel the need to raise my voice and be heard.

I think of Grace Paley’s charming story “The Loudest Voice”, in which the narrator says early on, “[T]he whole street groans: Be quiet! Be quiet! but steals from the happy chorus of my inside self not a tittle or a jot.” The narrator, a Jewish girl who is chosen for the school Christmas play because of her booming voice, makes the alien scene her own. Her loud voice is a metaphor for her self-assertion—but it is also literal, and is a source of power. At the end she says, “I was happy. I fell asleep at once. I had prayed for everybody: my talking family, cousins far away, passersby, and all the lonesome Christians. I expected to be heard. My voice was certainly the loudest.”

Chapter 16: In an interview about Lies about my Family, you said, “Having written the book, I can no longer remember the stories and experiences in it; I can remember only what I wrote.” Does this apply to your other work as well? Are they all a kind of exorcism of memory?

Hoffman: It does apply to my other works—but this “exorcism” is not something I intended, and I find it disconcerting (so maybe “exorcism” is the right sort of word for it). Being unable to experience these memories directly anymore, but only through what I’ve created out of them, feels like a loss. It’s the dark side of creating something, I guess. You get something new—the text; but you lose something in the process—the original material. Like a sculptor: Michelangelo. The block of marble no longer exists; instead there’s David. But then he made his Prisoners, emerging from the marble—where he hangs onto both the block and the sculpture. They’re called unfinished—but of course they are not. But I’m not Michelangelo, so all I get is a pile of shavings and chips on the floor.

Chapter 16: Are there any memories you have yet to exorcise but long to?

Hoffman: Right now I’m writing a novel, very light and funny. I’ve been loving the process—seeing how each word or event or character suggests the next. It’s been very liberating. I used to worry a lot that I wasn’t creative, because I couldn’t “make up” anything, but with this project I’ve let go of that worry—exorcised it!— and just followed things where they lead. And it sounds random, but it hasn’t been—I’ve got a whole relatively coherent draft. So, I don’t have plans to exorcise more memories any time soon, although of course that can change.

Simone Wolff is a second-year M.F.A. student at Vanderbilt University and head poetry editor at Nashville Review. Wolff’s poems and essays can be found in Souvenir, Coldfront, and The Likewise Folio, among other places.