Like Taking a Writer’s Yearbook Picture

Dwight Garner talks with Chapter 16 about being one of the last full-time book critics in the country

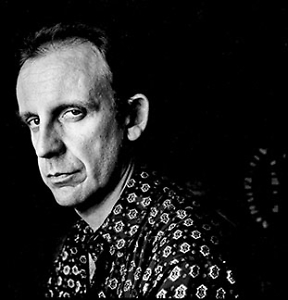

Dwight Garner has the kind of job every English major secretly dreams of but knows she’ll never get, just because such jobs don’t exist anymore: as a staff writer for The New York Times, Garner reads books for a living. He—like his colleagues at the daily paper, Michiko Kakutani and Janet Maslin—is one of the last full-time book reviewers left in the country.

The dearth of book critics has nothing to do with a cultural disdain for criticism. In fact, book reviews are alive and well on the Internet—at book blogs, at Goodreads, at online publications like Salon and Slate and The Daily Beast—but newspapers and magazines rarely employ a house critic anymore, and even The New York Times Book Review relies on the work of freelancers. It’s not easy to find a silver lining in the decline of local literary coverage, but if there must be only a handful of full-time book critics working today, it’s good news, at least, that one of them is Dwight Garner.

That’s because Garner is a master stylist and not simply someone whose job is to read books. Consider this passage from Garner’s 2010 review of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by former Memphis writer Rebecca Skloot: “I put down Rebecca Skloot’s first book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, more than once. Ten times, probably. Once to poke the fire. Once to silence a pinging BlackBerry. And eight times to chase my wife and assorted visitors around the house, to tell them I was holding one of the most graceful and moving nonfiction books I’ve read in a very long time.” Or this description of Clive James: “[T]ry, if you will, to imagine that David Letterman also wrote long, charming critical essays for The New York Review, published more than thirty books, issued memoirs that moved readers the way Frank McCourt’s do, knew seven or eight foreign languages, and composed poems that were printed in The New Yorker…. When England loses Clive James, it will be as if a plane had crashed with five or six of its best writers on board.”

That’s because Garner is a master stylist and not simply someone whose job is to read books. Consider this passage from Garner’s 2010 review of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by former Memphis writer Rebecca Skloot: “I put down Rebecca Skloot’s first book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, more than once. Ten times, probably. Once to poke the fire. Once to silence a pinging BlackBerry. And eight times to chase my wife and assorted visitors around the house, to tell them I was holding one of the most graceful and moving nonfiction books I’ve read in a very long time.” Or this description of Clive James: “[T]ry, if you will, to imagine that David Letterman also wrote long, charming critical essays for The New York Review, published more than thirty books, issued memoirs that moved readers the way Frank McCourt’s do, knew seven or eight foreign languages, and composed poems that were printed in The New Yorker…. When England loses Clive James, it will be as if a plane had crashed with five or six of its best writers on board.”

In his capacity as a nonfiction writer—and not as a book critic, necessarily—Garner will give a public lecture at Vanderbilt University in Nashville on January 16, 2014. Prior to the event, he answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Do you see the critic’s role as primarily that of a reporter, describing and commenting on what he sees? Or does the critic have a responsibility to influence and shape the culture itself? Or do you see your own role as something else altogether?

Dwight Garner: I want to enlighten and entertain and make fine distinctions about books and writers. I think if I sat down at my desk and thought, “Today I’m going to try to influence the culture,” I’d stick a fork in my neck and end it all.

Chapter 16: As virtually all local newspapers have stopped covering books by anyone other than bestselling authors, if they cover even those, the country’s largest newspapers—The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, etc.—have become the de facto newspapers of record for literature. Has this change in the book-reviewing landscape at all affected the way you approach your own work?

A new book gets so few reviews now that, writing about it in the Times, you feel you are taking its yearbook photo.

Garner: I hate the withering of this country’s book sections. Reynolds Price, the late North Carolina writer, said not long ago that a good first novel in America used to get ninety or so reviews. Now it might get a handful at best. The more voices the better. I envy critics in London, where there are seven or eight daily papers, and the critics all bounce their opinions off one another in print. It’s a scrum; it’s lively. A new book gets so few reviews now that, writing about it in the Times, you feel you are taking its yearbook photo.

Chapter 16: The withering of this country’s book sections in newspapers has been accompanied by a new online literary culture, and there’s a lot of talk—particularly among self-published authors—about how the diminishing influence of the so-called gatekeepers has had a democratizing effect on the book industry. Would you care to defend the book critic of old? What do readers learn from the Times that they don’t learn from Amazon reviews and Goodreads and blog tours?

Garner: Good writing is good writing—who cares where you find it? Good writing packs its own authority; it doesn’t need to appear in an old-school outlet to carry legitimacy and swat. I’m online a ton, and I like a lot of the stuff I see there. I groan at a lot of it, too. If you trust the reviews on Amazon, you are very gullible. (So many are written by an author’s friends—or enemies.) The “book critic of old” … he sounds so flatulent and Dickensian; who doesn’t want to shove a pie in that guy’s face? Some of them, though—I’m talking about daily newspaper critics here, men and women—were superb, and cities across a vast swath of America are the poorer for not having wide and easy access to their voices.

Chapter 16: The shuttering of book pages in daily newspapers around the country means more than just a net reduction in the number of reviews a good first novel gets; it also means that a lot of books by local and regional authors—authors a national paper like the Times probably wouldn’t ever touch—never get covered at all. Any ideas for how to solve the problem?

I hope some smart young people start their own publications, online or off. If he New York Review of Books were starting now, it would be a website.

Garner: One problem is that there are also fewer alternative weeklies—the kind of papers that care about books and about culture writ large. I hope some smart young people start their own publications, online or off. If The New York Review of Books were starting now, it would be a website. The barrier to entry is relatively low. God knows book reviewers are used to writing (at first, anyway) for very little money. Especially if the journal has high standards.

Chapter 16: Last year a hatchet job by William Giraldi in your paper ignited a debate among book reviewers about whether a negative review is ever warranted, especially of a literary book in an age when literary fiction is increasingly endangered. You weighed in on the side of those who believe that “not everyone gets, or deserves, a gold star,” and you make a compelling (dreaded word!) case for why “our critical faculties are what make us human.” Still, I wonder, isn’t there something between an undeserved gold star and an unreservedly negative review? Why not simply ignore the book that doesn’t merit praise and choose another from the great stack of options that come your way?

Garner: You’re right—the hardest thing to do is to develop a middle voice, to write interestingly about books that are (as are most) neither great nor abominable. I frequently don’t review books because they’re bad, especially from unknown writers. The last kind of piece I want to write is the piece that says, basically, “You know that thing you’ve never heard of? Well, it sucks.” But I value honest criticism, and not pulling punches. Book reviews aren’t written for the author’s mothers. They’re written for readers. I want to talk to the readers who come to my reviews as if they’re particularly smart, close friends.

Chapter 16: For the past two years, the VIDA Count, which considers gender bias in book reviewing, has tallied the number of female reviewers at and female authors reviewed by The New York Times Book Review, but they have not provided a count of reviews at the daily paper. Any sense of how things stack up in your corner of the building? Is this an issue that you and your editor and colleagues ever discuss?

Book reviews aren’t written for the author’s mothers. They’re written for readers.

Garner: I review books as a staff critic for the daily New York Times, not the Book Review, which appears on Sunday and where the reviews are all by freelancers. My two fellow critics at the daily, Michiko Kakutani and Janet Maslin, are both women. I have no corner of the building—like Michiko and Janet, I work from home. But I know that the editors of the Sunday Book Review (I was an editor there for a decade) have always been keenly concerned with this issue. The new editor, Pamela Paul, is a woman, the first female top editor in nearly two decades, and I know this is something that’s on her mind.

Chapter 16: Earlier this year, Margaret Sullivan, public editor of The New York Times, explained that you choose the books you wish to review without any knowledge of the books slated for review in the Sunday Book Review. Same thing goes for coverage of authors in the Sunday Styles section or The New York Times Magazine, and the result can sometimes be three different articles on a single author at the time of a new book release—or what novelist Jennifer Weiner calls “a hat trick”—in the most coveted newspaper space in the country. How do you respond to Weiner’s criticism?

Garner: The Times has daily critics and hires Sunday critics, and there are often two reviews of a book. I think this is indisputably a good thing. One, the more the merrier. Two, it’s important to have institutional voices—critics at the paper that readers have come to know. The “hat trick” is a relative rarity. It results when an editor (in the Culture section, or the magazine, or Styles, or elsewhere) assigns a profile of a writer. One example from 2013 was George Saunders, who was profiled in the magazine and reviewed twice. He deserved the attention.

The day I get tired of reading is the day I get tired of life.

I’m not sure what kind of safeguards you could put in place. Do you have the magazine editor call the Book Review editor and say, “Don’t run your review of Saunders; we’re profiling him?” Being profiled in the Times doesn’t mean that the fix is in. I’ve reviewed, quite negatively, writers who have been recently profiled in the paper.

Chapter 16: I’m guessing you must hear all the time from passionate readers who believe you have the perfect job. But in thinking about what it must mean to be a professional reader of books, I’m reminded of my college Shakespeare professor, who once confessed that he wished he’d bought a little gas station on the edge of town instead of becoming a scholar. Rather than allowing him to do what he loved for a living, he said, professionalizing the study of Shakespeare had merely turned what he loved into a job and ruined the love affair. What about you: do you ever wish you’d bought a gas station?

Garner: I worked in a gas station one summer, out on the margins of Florida’s Everglades (I had the all-night shift) and I don’t want to do that again—though I met some amazing characters. So no: no gas station regret. I still love reading; I get excited opening the mail, seeing what new stuff has arrived. The day I get tired of reading is the day I get tired of life. This love affair’s flame is still lit.

Chapter 16: You’re working on a biography of Tennessee native son James Agee. Is there anything you can tell us about the project—what drew you to it, or how it’s coming along, or when it will be released?

Garner: It’s a book about Agee’s work and life, due out in 2016. Agee was brilliant across so many genres; I’ve been attracted to his work since I was pretty young. Like Agee I’m from the Appalachians, and I’ve long felt a kinship of sorts.

Dwight Garner will appear at Vanderbilt University in Nashville on January 16, 2014, at 7 p.m. in Buttrick Hall, Room 101. The event is free and open to the public.