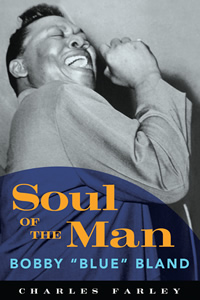

Lion of the Blues

Author Charles Farley tells the story of blues legend Bobby “Blue” Bland, invoking a pantheon of soul music’s most important faces and places

With Soul of the Man: Bobby “Blue” Bland, Charles Farley illuminates the life of a towering talent that The New Yorker recently called a contender for “voice of the century.” While Bobby “Blue” Bland may not be a household name outside the music community, he played a pivotal role in the blending of blues, country, and gospel that created the soul-music revolution.

Soul of the Man: Bobby “Blue” Bland tells the story of a lonely African-American boy who grew up in rural Tennessee. But after his family moved to Memphis in the 1950s, Bland began to make connections between the gospel music he’d been singing in church and the electrified blues he heard pulsating from the juke joints on Beale Street. Jammed with cameos from rhythm and blues legends like Little Richard, B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, and T-Bone Walker, Farley’s book expands Bland’s story to create a fully-realized vision of the evolving blues scene in the post-war South.

Touching on highlights like the release of Bland’s classic 1961 album, Two Steps from the Blues, and covering the awards and accolades Bland continues to receive, Farley has told the singer’s story with full-flavor and exhaustive detail. It’s a fitting tribute to a man whose music always walked a line between unbridled emotion and controlled, exacting expression.

Chapter 16: The book’s first chapters re-create the atmosphere of the Memphis music scene in the 1950s so completely that your story opens more like a film than a book. You immerse readers in rich detailing, but not in excessive language. What kinds of sources did you use in researching this aspect of the project?

Charles Farley: I tried to use as many primary sources as I could find—that is, accounts by people who were actually there in Memphis at that time, such as Rufus Thomas, David L. Cohn, George W. Lee, Margaret McKee, Fred Chisenhall, Louis Cantor, and others who lived and worked in the city and knew it well.

Chapter 16: Your portrayal of the racial segregation of that time is visceral and affecting. Paradoxically, one of the best quotations in the book comes from singer/songwriter/DJ Rufus Thomas, who recalls: “I told a white fella on Beale Street one night, I said, ‘If you were black for one Saturday night on Beale Street, you never would wanna be white anymore.’” What is Rufus getting at here?

Farley: Rufus Thomas always had a colorful way of expressing himself, and I wish he were still around to answer this himself. But, since he is no longer with us, I’ll give it a shot. During the first half of the twentieth century, Beale Street was a jumping place, particularly for African Americans. Pretty much anything went, as long as nothing untoward overflowed into the white part of town.

Farley: Rufus Thomas always had a colorful way of expressing himself, and I wish he were still around to answer this himself. But, since he is no longer with us, I’ll give it a shot. During the first half of the twentieth century, Beale Street was a jumping place, particularly for African Americans. Pretty much anything went, as long as nothing untoward overflowed into the white part of town.

But more importantly, it was almost exclusively an African-American enclave. African Americans could be themselves, could relax outside the daily constraints of the Jim Crow South. In other words, it was the one fun place for African Americans in an otherwise bigoted, rough, tough world. Sam Phillips, the white founder of Sun Records, put it a lot less pithily: “I was 16 years old, and I went to Memphis with some friends in a big old Dodge. We drove down Beale Street in the middle of the night and it was rockin’! The street was busy. It was active—musically, socially. God, I loved it!”

Chapter 16: Why did you decide to tell the story of Bland’s childhood a few sections into the book instead of right at the beginning?

Farley: Well, because Memphis and Bobby’s years there were a lot more interesting and exciting than his first fifteen years as a poor country boy in Rosemark and Barretville, Tennessee. As Bland himself said, “Basically, I didn’t do anything but go to the grocery store and help clean up there, or go to the cotton gin, which my dad ran. I used to hang around there and hustle up quarters and dimes doing a little extra work with the people that brought the cotton to be ginned. So there wasn’t really much to get into and nothing really exciting.”

Chapter 16: Bobby Bland isn’t a songwriter, a musician, or a dancer, but his voice is unique. You quote songwriter/music executive Arnold Shaw as saying that audiences loved Bland’s voice for its “combination of helplessness and self-assurance.” What, for you, makes his singing so special?

Farley: Bobby does have a great voice, of course, just a genuine, natural talent. It’s a deep, throaty, late-night blues voice tinged with a touch of country twang. But the thing, for me, that made him so special was the man’s ear. He could just hear in his head how a song was supposed to be sung. Songwriters loved him because he sang their songs “right,” and producers were always amazed how he could take a few words or a few bars and somehow turn it into a hit.

Chapter 16: Bland came of age as a singer during a time when the dividing line between black and white performers was rapidly disappearing. However, many readers might be surprised to learn how much Bland admired singers like Perry Como, Andy Williams, and especially Tony Bennett. Did they actually have an influence on his work?

Farley: Yes, Bobby has always been a great student. He listens to every kind of music and tries to take the best from each genre. When he was in the Army he was in a Special Services unit with Arthur Prysock and there he learned to sing ballads, and the best at singing pop ballads at the time were Como, Williams, and Bennett, as well as Nat “King” Cole, Charles Brown, and Jimmy Witherspoon, whom Bobby also admired and emulated.

Chapter 16: Music critic Dave Marsh has called Bobby Bland the “most country of all blues singers.” What did he mean?

Farley: Bobby’s first love, after gospel music, was country music. There were no black radio stations when he was growing up, so he listened almost exclusively to country music. When he went to Memphis in 1945, he wanted to become a country singer, but the white country music world was not quite ready yet for an African-American country singer. In addition, you have to remember that Bobby grew up in rural Tennessee. All people there, even black people, spoke—still speak—with a country twang. So Bobby was brought up to speak and sing country, and there’s no getting away from it, no matter how urbane and sophisticated the arrangements eventually became.

Farley: Bobby’s first love, after gospel music, was country music. There were no black radio stations when he was growing up, so he listened almost exclusively to country music. When he went to Memphis in 1945, he wanted to become a country singer, but the white country music world was not quite ready yet for an African-American country singer. In addition, you have to remember that Bobby grew up in rural Tennessee. All people there, even black people, spoke—still speak—with a country twang. So Bobby was brought up to speak and sing country, and there’s no getting away from it, no matter how urbane and sophisticated the arrangements eventually became.

Chapter 16: In one paragraph you compare a Bobby Bland show to both the call-and-response music of a Baptist church service and to a “slow love-making session.” How did Bobby’s music embrace both the pious and the profane?

Farley: Yes, soul music is basically a mixture of gospel and blues, but Bobby’s way of combining them is not particularly unique. He took a lot from his friend Sam Cooke, a gospel singer turned pop singer, in this regard, and you can hear Cooke in many of Bland’s early hits. As Bobby put it: “You haven’t did anything unless you’ve come through the church, because you don’t know how to feel certain things.”

Chapter 16: Your book presents Bland as a man whose perseverance and determination consistently helped him to overcome personal and career obstacles. (An alcoholic who quit drinking in 1971, he’s been recording and touring for more than half a century.) Why hasn’t Bland reached the kind of fame and popularity that other blues artists have achieved?

Farley: Good question, and the answers abound. Some say it’s because he doesn’t play an instrument, especially a guitar. Others claim that his sound is too uptown, what with all the horns, strings, and backup singers. Others contend that blues music is just too “old-timey” or too much of a downer for the young record-buying public.

But the fact is Bland never had a real manager. His record company managed his career, and his record company for twenty years was Duke, in the industry backwater of Houston, which marketed almost exclusively to African-American record stores and radio stations. It was not until Bobby was in his mid-forties that he recorded for ABC/Dunhill, and by then he was a bit too old to appeal to the wider, whiter, youth market.

Chapter 16: What’s your own favorite Bobby “Blue” Bland song? Why?

Farley: There are so many. I guess I would have to choose “Two Steps from the Blues” that was written by Texas Johnny Brown. I have no idea why, except it is the first song on the album of the same name, and it always makes me happy when I put it on and hear those first few familiar notes.

Charles Farley will discuss and sign Soul of the Man: Bobby “Blue” Bland at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on August 11 at 6 p.m.