Little Lost Girl

I hadn’t yet learned what being lost feels like

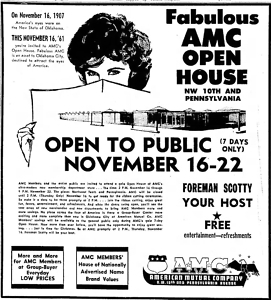

My father worked at a store called AMC, a “big box” before generics like Costco and Walmart became ubiquitous. Dubbed “The House of Name Brands” by the four brothers who opened it in Oklahoma City in the early 1960s, AMC was built to look like a giant circus tent with points made of poured concrete. It was massive and bright and cluttered inside. Everything was cheap.

That my father did not belong there is obvious to me now, since nothing about him was typical. In his 60s then, old to be the father of a young child, he had spent much of his life crisscrossing America on pre-interstate two-lane roads selling battery-powered light plants to farmers and floor tile to hotel owners and refrigeration to I-don’t-know-who.

At AMC he sold major appliances — refrigerators and dishwashers and washer-dryer combos, TV sets and air conditioners. In a decidedly shorts-and-flipflops kind of place, he maintained the polish of an earlier era. I never saw him go to work without everything pressed and buffed, from his wingtips to his fingernails, and without smelling like good cologne. His differentness, and thus mine, were questions both unasked and unanswered. Still, I felt a vague sort of pity toward children who had the regular kind of fathers — khaki-clad, burgers-on-the-grill, as-seen-on-TV mid-century American dads. I liked mine the way he was.

Sometimes he took me to work with him. My mother worked as a secretary, and I’m sure childcare was expensive on the long summer days when I wasn’t in school. He probably got away with it because he was a very good salesman, so he made a lot of money for the four brothers. Also, he did as he pleased — a trait I’ve been told I inherited. I was no trouble, though. At 7 or 8, I was a chubby little granny of a girl, bookish, and given to the self-sufficient imaginings of an only child. Sometimes I played a solitary version of “house” in empty refrigerator boxes near a back wall, but I was content to settle into one of the La-Z-Boy recliners on display and read Nancy Drew, half-listening to my father explain to customers how many British Thermal Units their window air conditioner would need to cool a room.

Inevitably during the afternoon lull, he would pull change from his pocket and send me to the snack bar for a Dr Pepper for us to share. I had the run of the place. Older ladies with those vintage names like Thelma or Gladys worked in departments along the way, waving when I passed by. I took my time, wandering through men’s shoes and the department that sold blenders and steam irons and the counter with ladies’ watches and jewelry and other things that glistened. The Barbie clothes were displayed under glass not far from the diamond rings, because that’s how AMC was. Eventually, I would get to the snack bar and back to Major Appliances with the pop. I always, dutifully, saved him half.

Sometimes during my wanderings, I would hear an announcement over the public address system for a child who had been lost. The microphone would crackle then I’d hear “We have a little lost girl,” followed by her name and a description. Boys were lost, too, though it’s the girls I remember. The announcements seemed plaintive, urgent, important. I pictured the lost one standing among strangers near the front registers, crying. I felt, frankly, superior. Who could get lost at AMC? I knew all the departments, all the shortcuts through luggage or sporting goods. Occasionally a customer would point me out to one of the clerks, assuming I needed to be rescued. “Oh, that’s Mr. Berry’s daughter,” I’d hear, as if that explained everything.

Secretly, though, when I heard those announcements, I felt I was missing out on some classic childhood experience, like the tooth fairy or a new puppy. I wanted, just once, to be a Little Lost Girl.

The department with ladies’ underthings was just down a ramp from Major Appliances. Bras and panties and half-slips were piled on low cabinets with doors underneath that slid open to hold extra merchandise. I wandered through sometimes. I never had a reason for any of my stops. I was driven by curiosity, a sort of territorial instinct, and I suppose a sense that some fundamental question about myself or life or, well, something might be answered among aisles of marked-down goods. I don’t think that’s unusual. Why, aside from practical needs, do any of us shop?

One day on my way to the snack bar, I noticed a sliding door open. The cabinet below was empty, and it occurred to me that if I climbed inside and closed the door, I, too, could be a Little Lost Girl. I would hear myself announced over the PA system. I would be important. I didn’t realize, of course, that in order to be Lost I first had to be Found by the lady who did the announcements. As my father liked to say, hindsight is 20/20.

The department clerk was busy and nobody else was around, so I wedged myself in, feet first. It was dark and muffled inside; the particleboard smelled dry, woody. I was aware of my shoes. I knew my father would not want me to get the cabinet dirty, so I pulled myself into a ball. I could hear the sounds of the store, a blend of voices and footfalls and a low constant thrum I had never noticed, like the store’s own secret. I didn’t know what to do then, so I waited.

After a while, I heard voices — my father’s and the clerk’s. “I saw her go by, Mr. Berry,” she said. “She must be here somewhere.” Their footsteps came closer until they were right outside. I pictured them looking around at all the places I wasn’t. I wanted to say, “I’m right here — Lost. Don’t you see?”

That’s a paradox, of course. I hadn’t yet learned what being lost feels like. Once, later, in the Christmas crowds at another store with my mother, I turned and she wasn’t there. Only ocean metaphors describe the terror — unmoored, adrift in a sea of strangers. Drowning. And then she emerged, her familiar face anchoring me. Nothing about that experience was what I longed for at AMC, but of course I could never be lost in a place as familiar as home.

In the cabinet, I must have made some slight noise, because suddenly the door slid open and the light from the store flooded in. There were my father’s wingtips and the gray fabric of his suit pants and the hem of the department clerk’s dress. They peered in. “Well, there she is!” the clerk exclaimed. My father, who was never angry with me, looked uncharacteristically annoyed. “What are you doing in there?” he said. I couldn’t explain.

I was disappointed, of course. I hadn’t gotten to hear my name on the PA system, hadn’t gotten to be a genuine Little Lost Girl. I had just been a girl hiding in a lingerie display — nothing more, though I would argue, nothing less. It was an experience I envisioned one way when it was really another. A lot of life is like that, I now realize.

What I didn’t know then was how fragile our little family really was, and how that store with its bright possibilities held us together. A few years later my father lost his sobriety after a decade of not drinking, and the AMC job along with it. I’ll never know why. I was approaching adolescence, and our old routines no longer interested me. And he had sometimes worked 12-hour shifts, selling on straight commission, so there were days he brought home no pay. He was probably, among other things, tired.

That day, though, on the way back to Major Appliances, he just said not to do that again. For a while he didn’t give me money for pop and I had to stay in his department. Then he gave in.

“Now come right back with it,” he said.

Copyright © 2021 by Jane Marcellus. All rights reserved. Jane Marcellus is a writer whose published work includes literary nonfiction, critical analysis, and journalism. Her work was listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays 2018, 2019, and 2020.