Long-Haired Country Boys

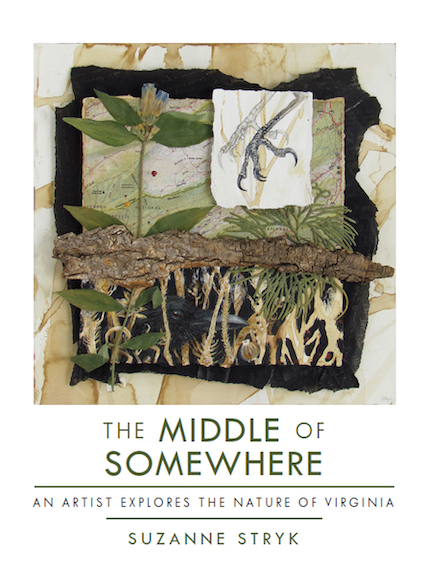

Scott B. Bomar talks with Chapter 16 about Southbound: An Illustrated History of Southern Rock

Rumbling out of the South at the beginning of the 1970s, Southern rock was a mix of back-to-basics rock and roll, blues, country, and soul—wrapped in a new vision of the American South. In his new book, Southbound: An Illustrated History of Southern Rock, Nashville native Scott B. Bomar chronicles the history of this uniquely American music and the musicians who created it.

Despite the chart successes of the Allman Brothers Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Marshall Tucker Band, and others, the artistry and innovations these musicians brought to rock music are often overlooked, casualties of persistent and pernicious prejudices about the South. Bomar tackles those oversights directly, building a case for the importance and inclusiveness of a style that sought to embrace the most admirable aspects of Southern life and culture while rejecting old bigotries. Drawn from interviews with dozens of musicians and illustrated with scores of band photos, album covers, label shots, and concert posters, Southbound gives the stories of individual bands as well as the history of a truly American music.

Despite the chart successes of the Allman Brothers Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Marshall Tucker Band, and others, the artistry and innovations these musicians brought to rock music are often overlooked, casualties of persistent and pernicious prejudices about the South. Bomar tackles those oversights directly, building a case for the importance and inclusiveness of a style that sought to embrace the most admirable aspects of Southern life and culture while rejecting old bigotries. Drawn from interviews with dozens of musicians and illustrated with scores of band photos, album covers, label shots, and concert posters, Southbound gives the stories of individual bands as well as the history of a truly American music.

Bomar recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: There’s a great quote from Gregg Allman near the start of the book: “‘Southern rock’ is like saying ‘rock rock.’ Rock and roll was born in the South.” How did you arrive at a definition of Southern rock that was workable for the book, and what is that definition?

Scott B. Bomar: Elvis, Little Richard, Jerry Lee—all those guys came from the South, and understanding that is part of the Southern-rock story. When people use the term “Southern rock,” however, they’re generally talking about the Allman Brothers Band, the Marshall Tucker Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and so on. What happened was that you had these kids growing up on blues, soul, country, and rock in places like Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, or North Carolina. They had shared cultural experiences as Southerners, but they also had the shared experience of becoming long-haired music freaks in an environment that was fairly conservative. Even though Southern rock is often regarded as “redneck” music today, a “redneck” in the 1960s was a guy with a crew cut who just might be inclined to kick the ass of a freaky long-haired rocker.

So these guys were pretty countercultural and tended to stick together. As they formed bands and became successful in the early 1970s, the fact that they were Southerners made them unique in the wider world of freaky long-haired rockers. So they were fish out of water at home because they were rockers, and they were fish out of water in the rock world because they had funny accents. Needless to say, they tended to bond because they understood one another. Charlie Daniels told me that Southern rock is a genre of people more than it is a genre of music, and I think that’s a pretty good definition of something that’s a little slippery to fully define.

But I did write a book about it, so I had to come up with something more precise. In the introduction I listed four criteria that guided my decisions about who would—and would not—be included in the book. Sometimes people skip introductions, but this is one of those cases where it actually frames the entire book. And maybe it will even start a little debate.

But I did write a book about it, so I had to come up with something more precise. In the introduction I listed four criteria that guided my decisions about who would—and would not—be included in the book. Sometimes people skip introductions, but this is one of those cases where it actually frames the entire book. And maybe it will even start a little debate.

Chapter 16: You’re young enough to have missed the original heyday of Southern rock. How did you first discover the music?

Bomar: My dad is in the music business, so I was surrounded by music as early as I can remember. Maybe I had some records for kids when I was little, but if I did, I don’t recall them. I was into Elvis and the Beatles at a very young age, so I was always looking to the past when it came to my musical choices. I started playing guitar around age twelve or thirteen. It was the 1980s, so what was on the radio wasn’t very guitar-heavy. That’s when I really got into classic rock, and it was around that time that 104.5 The Fox was just getting going in Nashville. Southern rock was a big chunk of their classic rock programming, so I was always hearing the Allmans, Skynyrd, Wet Willie, Marshall Tucker, ZZ Top, 38 Special, and those kinds of Southern groups on the radio. This was also around the time that everyone was embracing CDs, so I was building my music collection with the CD issues of classic albums.

Chapter 16: What led you to write this book?

Bomar: My friend Randy Poe had done a biography of Duane Allman a few years back. His publisher, Backbeat Books, wanted to take a stab at a general history of Southern rock, and approached him about it. Randy was involved with another project at the time, so he recommended me. I was working on a different book, but this opportunity intrigued me, so I set it on the back burner, switched gears, and threw myself into Southern rock. The fact that the opportunity fell in my lap turned out to be a great thing because I didn’t have any particular preconceived ideas about how I wanted to approach it. I just jumped in with both feet, immersed myself in Southern rock, and let the history itself decide how I would frame the story. It was a really great adventure.

Chapter 16: From its beginnings in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Southern rock has had a certain stigma attached to it, often by non-Southerners but also by Southerners who wanted to disassociate themselves from the “redneck” image of the South. Speaking for myself, I had to go through a process I like to call “coming to terms with my Inner Skynyrd” to fully appreciate the music. How do you address this stigma?

Chapter 16: From its beginnings in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Southern rock has had a certain stigma attached to it, often by non-Southerners but also by Southerners who wanted to disassociate themselves from the “redneck” image of the South. Speaking for myself, I had to go through a process I like to call “coming to terms with my Inner Skynyrd” to fully appreciate the music. How do you address this stigma?

Bomar: I think we all have to come to terms with where we’re from. For example, I never once visited the Grand Ole Opry when I lived in Nashville. I moved to Los Angeles when I was twenty-four years old and have since been to the Opry plenty of times. It wasn’t until I was separated from the culture of my growing-up years that I came to really appreciate it. I think I’m also a bit of a contrarian, so embracing traditional country music or Southern rock as a Californian came naturally to me.

But, yes, there is a stigma, and there is imagery that sometimes accompanies Southern rock that people find off-putting. The Confederate flag is the most obvious example. I truly believe that the bands that used that symbol in the ’70s intended it only as a statement of regional pride in the face of the larger rock world that might have viewed them as oddities because they were Southern. But it’s a symbol that can also be very provocative and painful, and understandably so. My biggest fear about the book was that some graphic designer in New York would splash a big Rebel flag across the cover with a bottle of whiskey and a skull-and-crossbones, which is not what Southern rock is really about. I wanted to come up with a book that would appeal to long-time fans but also hopefully entice those who have let some of the stereotypical images stand in the way of giving the music a fair chance. I particularly encourage those who might have dismissed Southern rock on image alone to pick up this book and let some of their assumptions be challenged.

Chapter 16: In the process of writing, did you have any great revelations—did your interviews and research lead to conclusions about the music you didn’t expect?

Bomar: I interviewed nearly fifty people, and I was a little intimidated by the prospect of talking with some of them. I guess a few of those Southern rock stereotypes came into play because I had the idea that several of these guys were going to be really gruff, rough-and-tumble, rock-and-roll badasses. Instead, they were some of the sweetest, most thoughtful, and encouraging people you would ever want to meet. Talking to ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons was like talking to a fellow music nerd. He’s as excited about his own musical heroes as he was when he was a teenager. Jimmy Hall from Wet Willie and Doug Gray from the Marshall Tucker Band were two of the nicest guys I’ve ever spoken with. In fact, Doug wound up writing the foreword for the book. I think the interview that made me most nervous beforehand was Charlie Daniels. He’s particularly outspoken and very political. I think he and I probably feel quite a bit differently about certain issues, so I didn’t know what to expect from our conversation. As it turns out, he was one of the most disarmingly warm and genuine people I’ve ever spoken with.

Chapter 16: I enjoyed the way the book’s separate chapters focus primarily on the individual stories of different bands, but in the big picture they interlock to form the greater story. How did you decide to follow this format rather than trying to tell the story in a strict chronological format?

Chapter 16: I enjoyed the way the book’s separate chapters focus primarily on the individual stories of different bands, but in the big picture they interlock to form the greater story. How did you decide to follow this format rather than trying to tell the story in a strict chronological format?

Bomar: Southbound is a substantial book. I wrote a lot. In fact, my original manuscript was literally twice as long as what was published. In addition, there are around 400 images in the book, so trying to figure out how to organize all that in a way that made any sense was a bit of a challenge. I came up with the idea of devoting dedicated sections to some of the key bands as a way to satisfy the different readers who might pick up the book. People who are music geeks like me can read it cover to cover to get the big picture. Some people might just want to read a handful of chapters about their favorite bands. It can also serve as a reference source for those who want to look up information about a particular group. I wanted the book to be valuable to everyone who reads it, from the casual fan to the person who wants to dig deep, and I think we were able to pull that off.

Chapter 16: How has the legacy of Southern rock endured, and how has it influenced other genres like mainstream rock, Americana, and mainstream country?

Bomar: Charlie Daniels is almost universally regarded as a country artist today, but in the 1970s he was a Southern rocker. What’s wild about that is his music didn’t change. People like Charlie and Hank Williams Jr. introduced Southern-rock elements into country music to such a degree that country music pretty much is Southern rock now. What you hear on country radio today has much more in common with Lynyrd Skynyrd or the Marshall Tucker Band than it does with Johnny Cash or George Jones. What used to be country is now Americana, and what used to be Southern rock is now country.

The Allman Brothers Band had a tremendous influence on the jam-band movement, which is still very much alive and well. I hear a lot of Allman’s influence in the Black Crowes, for example. I look at groups like Blackberry Smoke or the Cadillac Three, which are marketed as country, but they are straight-up Southern-rock bands. In fact, Blackberry Smoke and the Black Crowes are two of my favorite Southern-rock groups. One is regarded as country, and the other as rock, but I hear very strong connections between the two.

What’s funny is that most of the musicians I interviewed for the book resisted the Southern-rock label completely, so I’m not sure that musical categories have any real meaning anymore. I guess there are so many influences to be appreciated and absorbed that we’ve arrived at a point where good music is good music, no matter what you decide to call it.

Chapter 16: Okay, Lynyrd Skynyrd—greatest American rock band ever? Even if you don’t agree fully, how would you lay out the case as an attorney might?

Chapter 16: Okay, Lynyrd Skynyrd—greatest American rock band ever? Even if you don’t agree fully, how would you lay out the case as an attorney might?

Bomar: Ha! I couldn’t point to a single group and commit to calling them the greatest American rock band ever. I think a solid argument could be made for the Allmans, The Band (Canada is part of the continent, after all), CCR, Sly and the Family Stone, the E-Street Band, the Heartbreakers, or the various incarnations of Prince’s New Power Generation. I think one could even make a compelling case in favor of bands as opposite as the Eagles and the Ramones.

I certainly think Lynyrd Skynyrd deserves to be part of that conversation. They embody the very essence of American rock and roll in that they were working-class kids who started out playing in garages and clawed their way up through a lot of hard work. People probably don’t realize that in the early years, Lynyrd Skynyrd rehearsed all day with at least as much focused commitment as one would apply to a more traditional career. They put all their energy and sweat into honing a sound that was pure rock-and-roll energy. They had three guitars wailing away, but it wasn’t cacophony. The songs were tightly arranged, and they were songs. They were well crafted and honed to perfection.

Ronnie Van Zant was a great lyricist and a great vocalist. We’ve heard “Sweet Home Alabama” and “Freebird” so many times that we take them for granted, but think about how good those songs are in terms of their melodies and their arrangements. If you listen to Skynyrd’s albums, you’ll hear the uniquely American influences of blues and country music that gave birth to rock and roll, but the band was never mimicking those sounds. Instead, they incorporated them seamlessly into their style. Rock critics who should know better have dismissed Skynyrd for ages, but go back and listen to their records from the 1970s. They’re easily as good of a band as the Rolling Stones.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.