Louisiana Man

Doug Kershaw’s memoir is as wild as they come

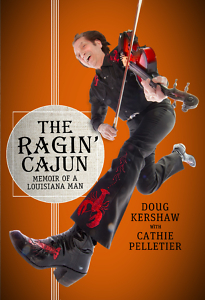

Country music scholars can agree on a few things about Doug Kershaw: He is one of the most famous Cajun musicians of all time; he survived a rough upbringing in southern Louisiana, and he has had a very successful musical career marked by great personal turmoil. But none of those facts convey Kershaw’s unforgettable music, wild fiddling style, and flamboyant stage presence. Anyone lucky enough to have seen him perform knows what I’m talking about.

The Ragin’ Cajun: Memoir of a Louisiana Man tells Kershaw’s life story from his birth on a houseboat in southern Louisiana to international stardom. Some of the material here will be familiar to fans, like the tale about 5-year-old Kershaw cracking the family fiddle and then saving himself from a whipping by playing it beautifully. But there are plenty of stories I hadn’t read before, and the book has an engaging, conversational tone, like you’re sitting on a houseboat on Lake Arthur with Kershaw as he relates his tumultuous history.

The Ragin’ Cajun: Memoir of a Louisiana Man tells Kershaw’s life story from his birth on a houseboat in southern Louisiana to international stardom. Some of the material here will be familiar to fans, like the tale about 5-year-old Kershaw cracking the family fiddle and then saving himself from a whipping by playing it beautifully. But there are plenty of stories I hadn’t read before, and the book has an engaging, conversational tone, like you’re sitting on a houseboat on Lake Arthur with Kershaw as he relates his tumultuous history.

The book begins with Kershaw’s Acadian family lineage before turning to a fascinating first-person account of his early years, and he doesn’t mince words about the toll that alcoholism and poverty took on his family and others around them. Though his father was a good financial provider, his drinking made him a ticking time bomb. One night, drunk and “piloting the boat with his foot so he could play the accordion with his hands,” Kershaw recalls, Daddy Jack decided he wanted his wife, Mama Rita, to throw their children in the river, which was full of alligators. He threw a metal pipe across the boat, hitting her in the head. With blood streaming down her face, she stood between her enraged husband and her babies. With the help of Kershaw’s uncle, the family made it home, but a short time later Mama Rita decided it was time to leave.

The family wound up living in town, where young Kershaw realized that he could make decent money playing all the fiddle tunes he had heard since birth. He was soon supporting his family with music, but the transition to this new life was uncomfortable for a child who had only known life on the houseboat. Before coming to town, Doug Kershaw did not own a pair of shoes, speak English, or know that to many people “Cajun” was a dirty word.

Kershaw often got in trouble at school as he struggled to learn English. His inspiration finally to become bilingual was a jukebox he overheard while busking. “Ernest Tubb was a better reason for me to learn English than a thousand ass-paddlings,” writes Kershaw of his first encounters with hillbilly music. “I also took notice that day of how the jukebox didn’t care one bit what the language was. It just went ahead and sang its heart out. No prejudice there, especially in those days before the music industry had a chance to brainwash the consumer.”

Kershaw often got in trouble at school as he struggled to learn English. His inspiration finally to become bilingual was a jukebox he overheard while busking. “Ernest Tubb was a better reason for me to learn English than a thousand ass-paddlings,” writes Kershaw of his first encounters with hillbilly music. “I also took notice that day of how the jukebox didn’t care one bit what the language was. It just went ahead and sang its heart out. No prejudice there, especially in those days before the music industry had a chance to brainwash the consumer.”

Kershaw became such a good fiddler that he and Mama Rita were invited to join local Cajun player Zenis LaCombe’s band, which played at Lake Arthur’s notorious bar, Bucket of Blood. The place was true to its name. “It wasn’t considered a good night at the Bucket unless there were at least three fights and a knifing,” writes Kershaw of this time. Thankfully, the Bucket put up a wire fence to protect stage performers after 9-year-old Kershaw began playing there regularly.

The Ragin’ Cajun delivers a fairly exhaustive account of Kershaw’s life, but the short version is that he rose through the musical ranks through sheer will and hard work, eventually writing one of his biggest hits, “Louisiana Man,” in Nashville. “I wrote my signature song at the one and only pickin’ party I hosted at my little apartment, located across from Acuff-Rose. It was a bona fide dump, but we were used to drifting in and out of dumps back then. Roger [Miller] was broke. Willie Nelson was broke. Hell, back then God was probably broke.”

Though the journey is marked by various addictions, numerous car repossessions, multiple divorces, and an arrest, Kershaw — with the help of his co-author, novelist Cathie Pelletier — so endears himself to readers by the end of this memoir that he feels like a friend. The book adheres to Kershaw’s self-professed performance philosophy: “All I had to do was entertain the crowd as well as I could. Then, if I got out of town fast enough, nobody could kick my ass.”

Sarah Carter holds an M.F.A. in creative writing from the Sewanee School of Letters.