Love for Life

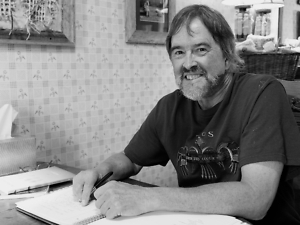

A writer’s grateful tribute to poet and teacher Bill Brown (1948-2023)

Mine was the typical nerd-kid’s story: I loved to read, and that made me an Other for most of my school years. All that changed in the autumn of 1984, when I climbed the stone stairs at 700 Broadway with a few hundred fellow nerd-kids and discovered what it was like to belong somewhere. Hume-Fogg, Nashville’s first academic magnet, was a grand experiment then in its second year. And for me and many of my classmates — kids from every zip code, ethnicity, and economic background in Davidson County — that stately old building was the first place we could openly share our love of literature, Latin, calculus, or poetry with our peers without becoming outcasts.

That experience was no accident. The faculty founders of HFA created that environment deliberately, with tremendous effort that was largely invisible to us at the time. What we could see was their enthusiasm and mastery in the classroom. My freshman English teacher was a shaggy-haired hobbit-poet in horn-rimmed glasses. Most of Bill Brown’s students towered over him, but his sheer exuberance left us gazing up at him in wonder. We grumbled with secret pride about the 25-page journals he assigned us to keep as we read Orwell, Huxley, and Shakespeare, but those assignments tricked us into filling notebooks until, magically, we found that we had something to say.

Sophomore year, I ascended to the cavernous, mostly deserted fourth floor for Brown’s creative writing class, a shag-carpeted salon where kids circled up in bean bag chairs and translated the world into poetry. His one-on-one edit sessions were a gift and a revelation. Here was an accomplished poet who took our work seriously and offered detailed, informed critiques, as if we were fellow writers and equals. I recall one session in particular when I wept as I read aloud a poem about skipping softball practice that summer, just before our beloved coach died of cancer. I don’t recall Brown specifically trying to comfort me. He just listened, then suggested a simple, perfect title: “Last Practice.” Somehow, even then I grasped that spilling my howls of regret onto the page with Brown as reverential witness gave me something deeper than comfort.

The broader lesson has been with me ever since: Writing could be much more than a tool for earning a grade or a living; it could be a personal philosophy of wholehearted attentiveness and a methodology for naming all the grief, guilt, joy, and amazement of existing while human on a broken, beautiful planet.

Brown modeled this zeal for his life’s work, both in the classroom and on student hiking and backpacking trips he led with his friend Tony Beasley, Hume-Fogg’s biology teacher. Those guided journeys of discovery not only nurtured young poets and burgeoning naturalists; they fostered a community, one that has remained tight-knit since the 1980s. Since Brown’s death in December, there’s been an outpouring of grief and loving remembrance among HFA alumni. On a private Facebook page for Hume-Fogg’s first four graduating classes, Amy Evans, a 1987 graduate, posted that Brown “helped us know ourselves and grow our roots to our home: our friends, our mentors, these hills, these rivers, the starry skies, and the city hum.”

Brown modeled this zeal for his life’s work, both in the classroom and on student hiking and backpacking trips he led with his friend Tony Beasley, Hume-Fogg’s biology teacher. Those guided journeys of discovery not only nurtured young poets and burgeoning naturalists; they fostered a community, one that has remained tight-knit since the 1980s. Since Brown’s death in December, there’s been an outpouring of grief and loving remembrance among HFA alumni. On a private Facebook page for Hume-Fogg’s first four graduating classes, Amy Evans, a 1987 graduate, posted that Brown “helped us know ourselves and grow our roots to our home: our friends, our mentors, these hills, these rivers, the starry skies, and the city hum.”

In 2013, I interviewed Brown and other founding faculty members for a short documentary about HFA’s origins. Those interviews opened my eyes to the unsung, above-and-beyond work they did. I laughed, astonished, when Brown told me that for the first two years, he and AP English teacher Alan Kaplan graded our essays together by reading them aloud. Every. Single. One. I learned that other faculty members helped students with transportation, money, and places to stay — all because they believed fiercely that every kid, regardless of resources, deserved a world-class education. To Brown, who led Hume-Fogg’s creative writing program for 19 years until his retirement in 2003, a real education meant prioritizing the lasting joy of intellectual inquiry over mere scholastic ladder-climbing. And to him, the act of creation was a far more meaningful educational tool than taking tests.

“All of this had to do with our love for life,” Brown told me that afternoon in 2013, his face aglow with sunlight and memory. Finally, I understood Brown’s most lasting gift to us: He loved his life, and he continued to enjoy writing, nature, poetry readings, and mentoring until his final days. “Loving something can save you,” he writes in a poem titled “With the Help of Birds” from his 2008 collection, Late Winter. Maybe, in unabashedly modeling his own loves, Brown was teaching us how we could save ourselves — by taking shameless joy in literature, friendship, nature, and a satisfying life’s work. And in so doing, I’m guessing he also saved himself.

*The clip below is from Kim Green’s 2013 interview. The full documentary, Old School: The Making of Hume-Fogg Academic HS, can be seen at her website.

For more on Bill Brown’s life and work, read Chapter 16‘s 2010 interview, our feature story about a 2011 art and poetry collaboration in Memphis, and excerpts from his work here, here, and here.

Copyright © 2024 by Kim Green. All rights reserved. Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators. She is the co-writer of Chantha Nguon’s memoir Slow Noodles, forthcoming in February 2024 from Algonquin Books.