Lucille’s Better Half

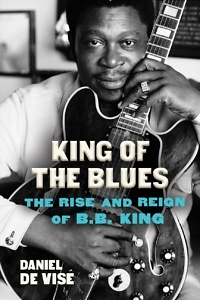

Blues legend B.B. King gets the royal treatment from biographer Daniel de Visé

King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King is touted as the first “full-length and authoritative” biography of the Mississippi Delta-born, Memphis-minted guitar great. It was worth the wait and (at 496 pages) the weight, as author Daniel de Visé has a whole lot of living and a lifetime of blues to chronicle.

B.B. King, who died in 2015 at age 89, gets the royal treatment from his biographer, and rightly so. We get it all, a life in full, from dirt to gold, roadhouse to the White House, tractor (the mode of transportation on his first date with future first wife Martha) to Cadillac (a pink-and-cream El Dorado with blue and white tires and a battery-powered TV).

We see B.B. as young Riley, stuttering and girl-crazy, getting a blues man’s version of religion when he sees sanctified preacher Archie Fair play guitar in church on Sunday. Reverend Fair “filled the room with the low thunder of his voice and the sweet tang of his guitar,” de Visé writes.

We see Riley seduced by the “shapely curves” of a guitar and entranced by the 78 rpm sounds of Blind Lemon Jefferson, Bessie Smith, and Lonnie Johnson at the cabin of his great-aunt Mima, the snuff-dipping free spirit who was “the settlement’s resident hipster.”

And we see his slow, hard education on the guitar — the early fumblings, the search for his own sound, and, crucially, his musical influences.

The author is especially good at showing that, while King was born in Mississippi and grew up when early legends of the genre were active, he wasn’t shaped just in the usual way. You can hear Robert Johnson in Muddy Waters and Charley Patton in Howlin’ Wolf. But King’s influences ranged from Hawaiian and country lap steel players to the Belgium-born jazz legend Django Reinhardt. Closer to home but still beyond the borders of the Magnolia State, he drew from Lonnie Johnson (Louisiana) and fellow blues great T-Bone Walker (Texas), plus jazz guitar hero Charlie Christian (Texas born, Oklahoma raised). And in Memphis, where a WDIA show pitching Pep-ti-kon tonic turned into a DJ gig, the rising blues man had unfettered access to records — a world of sound.

“Never, perhaps, had a blues guitarist drawn from such diverse influences,” de Visé writes. “And now, with an entire radio station at his disposal, B.B.’s ears were about to explode.”

This is how artists become great. This is how B.B. became singular. By taking in everything that turned his head or caught his ear. By making it all his own. Great artists are scavengers before they’re anything else, scroungers of the first order, but the wonder is in what they do with it all. They see, hear, feel, divine what others can’t. They take what they’ve gathered and build something grand: One man’s found parts is another’s pink-and-cream Caddy El Dorado.

This is how artists become great. This is how B.B. became singular. By taking in everything that turned his head or caught his ear. By making it all his own. Great artists are scavengers before they’re anything else, scroungers of the first order, but the wonder is in what they do with it all. They see, hear, feel, divine what others can’t. They take what they’ve gathered and build something grand: One man’s found parts is another’s pink-and-cream Caddy El Dorado.

This is de Visé’s triumph, explaining how B.B. went from being the “weakest link” at his first recording session to leading his own blues orchestra. How he became a guitarist young players studied and jazz greats like Miles Davis adored. How he became an innovator on his way to becoming an icon:

B.B would never master the lap steel. But with his strong, thick, cotton-picking fingers, he found that he could bend and trill the strings of his own Gibson guitar to similar effect, and he could do it without a slide. He called this new technique the “Butterfly.”

Now he was an artist, this blues man who would be king. He was out from under the spell of his influences: “These men had taught their guitars to sing. B.B. taught Lucille to cry.”

Ah, Lucille — B.B.’s name for his beloved guitar. If you can’t name a B.B. King song other than “The Thrill Is Gone,” you know about Lucille. You may even know the story of how she got her name, one December night in tiny Twist, Arkansas.

But if you’re not a serious fan or student of his playing, you probably just know B.B. as the blues man who was always there — who didn’t flame out or disappear, didn’t die from drugs or guns or crossroads devilment. He played on, whether people were buying his records or not. He played on, whether the show was at the Regal Theater in Chicago or the Moon-Glo Roller Rink in Kent, Ohio.

B.B., then, was the king we kind of took for granted.

He wasn’t Robert Johnson of crossroads soul-selling fame. He wasn’t Skip James or Mississippi John Hurt, who cut early classic sides, disappeared for decades, and then were rediscovered as real-life ghosts who still had their guitar chops. He wasn’t Muddy or the Wolf, so identified with one city and label — Chicago and Chess Records— as to become synonymous with the blues itself, electric division.

That’s why we needed a “full-length and authoritative” biography of the man, the artist, Lucille’s better half, the King of the Blues. Now we have it. It’s good and worthy and something more: essential.

Is reading it as satisfying as hearing BB’s early singles on the RPM label or the Live at the Regal album — or the sublime slink of “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean,” the first song off B.B.’s final studio album, produced by T Bone Burnett when B.B. was 82 and thought to have nothing left?

Well, whoever said you had to choose?

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novel Long Gone Daddies (2013) and Everybody Knows (forthcoming from JackLeg Press, 2022). His short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.