Making Good Trouble

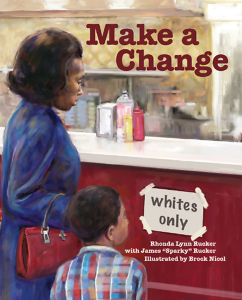

Rhonda Rucker discusses her new picture book, Make a Change, about a slice of Knoxville history

For the last four decades, Rhonda and James “Sparky” Rucker, who live in Maryville, have performed together for schools, libraries, and festivals all over the world, singing in the American folk tradition. Many of their educational programs touch upon African American history, particularly the civil-rights movement. Rhonda, who also writes children’s and young-adult books, brings this very topic to her newest picture book, Make a Change.

In fact, it is Sparky who lived the story in the book, which is set in Knoxville in 1960. When a group of Knoxvillians organize a pray-in to protest racial discrimination at Rich’s Department Store, a young boy named Marvin, based on Sparky himself, learns a meaningful lesson about change—and making assumptions about others. Illustrated by Brock Nicol, it’s a compelling story that captures the determination of peaceful protesters years before the Civil Rights Act outlawed racial segregation in stores and other public places.

Rhonda Rucker answered questions via email about the true story that informed her newest children’s book.

Chapter 16: Can you talk about the real-life experience in Knoxville upon which this story is based?

Rucker: In February 1960, only days after the famous Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-ins, Knoxville College students began making noise about the segregated lunch counters in their own hometown. For months, students at the traditionally black college tried negotiations, but when those efforts failed, they realized more drastic measures were needed. In June 1960, they began sit-ins at Rich’s Department Store and many other Knoxville businesses. Demonstrators continued their protests until most counters finally opened to all customers in late July.

Rich’s Department Store, however, was resistant to change. In October, it briefly had a stand-up snack bar in the basement open to all customers. But its Laurel Room restaurant was still segregated, and students continued to demonstrate. By January 1961, Rich’s closed its Knoxville store, preferring to leave town rather than open its counters to all people. So the protesters essentially ran them out of town!

Sparky, my husband, was actually fourteen when these events happened, a few years older than Marvin, the boy in my picture book. I made the character younger to make the story more relevant for preschool readers.

Chapter 16: What was the biggest challenge in fitting this story into picture book format?

Chapter 16: What was the biggest challenge in fitting this story into picture book format?

Rucker: Teaching tiny kids about the civil-rights movement can be difficult. Their sense of history and timing isn’t fully developed yet, so they can have trouble understanding how long ago (or how recently) events have happened. In our school programs, we often give a general overview of African American history, beginning with slavery in the early 1600s and ending with the civil-rights movement. More than once, very young children have asked Sparky if he used to be a slave. On the other hand, they are usually excited when they learn he was part of the civil-rights movement and knew people like Rosa Parks.

Another challenge is the inherent violence of the movement. In Birmingham, police dogs and fire hoses were turned on children as young as six, so those kids experienced the brutality firsthand. They boldly continued to demonstrate anyway, filling up Bull Connor’s makeshift jails. In my picture book, I only hinted at the possibility of violence. Unfortunately, it was a fact of life for many young people growing up in Jim Crow America, and it continues to be present for many children today.

Over the years, we’ve found that the concept of fairness helps preschoolers understand civil rights. No matter how young, they comprehend that it’s unfair to treat one person differently from another.

Chapter 16: Had you been familiar before this book with the artwork of Brock Nicol? What was it like for you to see his illustrations?

Rucker: No, I had not been familiar with Brock Nicol’s artwork before Pelican chose him to be the illustrator. However, once I saw his portfolio, I was completely on board. The powerful pictures he produced for this book blew me away! They vividly depict the conflict and struggle of people trying to make this a better world.

Chapter 16: Have you had a chance to share this story with children/students yet, particularly in Knoxville?

Rucker: Since its publication about six weeks ago, we haven’t visited any Knoxville-area schools. However, we’re in the planning stages with teachers and librarians, so those programs will happen. Sparky has told this story on stage to children and adults for decades, in Knoxville and across the country. I have always thought it would make a good children’s book, with its potent message. It’s even more relevant in today’s social climate.

Earlier this year, we performed at a children’s festival in Knoxville and a family concert in the next county, where we talked about Sparky’s involvement in the civil-rights movement. Audiences liked it when he said, “My mama took me to my first civil-rights demonstration. How cool is that?”

Chapter 16: How does your music inform your storytelling and writing?

Rucker: We use stories to introduce songs, so in our minds, they go together. Every song has a story. For example, I tell the story of how Harry Burn, a Tennessee state representative, cast the deciding vote that helped pass the Nineteenth Amendment. It all hinged on a letter from his mother, urging him to vote for women’s suffrage. Then we play the song, “Uncle Sam’s Daughter.”

Sparky tells the story of Sherman’s March to the Sea before we sing “Marching Through Georgia.”

Chapter 16: What’s next for you both? Any more books in the works?

Rucker: Sparky is working on a memoir of his life’s work as an activist, musician, and folklorist. The working title is The Care and Feeding of a Radical Folksinger. I am putting the finishing touches on A Mighty Stream, a young-adult novel set against the backdrop of the Birmingham Children’s Crusade. Those students became genuine heroes, transforming public opinion and energizing the civil-rights movement.

Julie Danielson, a former school librarian, blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast and writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews and BookPage. Her first book, Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, was published in 2014.