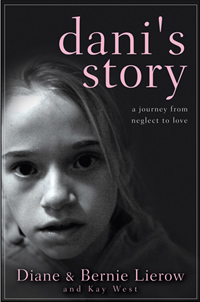

Maternal Instincts

Kay West documents an adoptive mother’s love for a tragically abused child

Six years ago, state authorities in Florida investigated a child neglect case so vile and gut-wrenching that even an experienced social worker and a cop found themselves vomiting at the scene. In a small house full of filth, barely clothed and confined to a foul closet, was a profoundly underweight, socially underdeveloped, acutely neglected six-year-old girl named Dani. She had bug bites and scratches on her body, couldn’t speak or play, wasn’t toilet trained, and by all appearances had never been talked to, smiled at, or hugged. She lived in the house—if you could call it living—with her mother and two half-brothers, and she was lucky even to be alive.

After her rescue, authorities had little hope that a child so utterly damaged would find a loving home. But they didn’t know Diane and Bernie Lierow, a couple who saw Dani’s photo and felt drawn to adopt her. Nashville author Kay West has written a book about how the Lierows came to welcome Dani into their family. She recently spoke with Chapter 16 by phone about Dani’s Story.

Chapter 16: I remember seeing a Pulitzer Prize-winning article by Lane DeGregory in the St. Petersburg Times about Dani several years back, and it was difficult even to read. I guess it’s fair to say this project took an emotional toll?

Kay West: It did, yes. As part of doing the book, I went to Florida and went with the detective to see the house where she was kept. I retraced the steps from when she was taken out to when she went to go live with the Lierows. Seeing that house, I think, is what was so devastating. It really took a few days to get over that. The story did mention that she made this noise, this sort of guttural noise, and in fact when I talked to the neighbors where Bernie and Diane lived after they brought Dani home for the first time, those neighbors said they could hear her scream—through two air-conditioned homes.

I had this impression that the house where she had been kept by the biological mother was out in the middle of nowhere. In fact, it was no more than twenty-five feet away from the door of the next house. And across the street from a church. It was a street filled with houses. There’s no way that people didn’t know something was going on. Between that and the fact that Florida’s Department of Children & Families had come twice to the apartment where she lived when she was younger—two and three years old—and just left her there. Had they intervened then, it would be a far different story. She would probably be able to talk now.

I had this impression that the house where she had been kept by the biological mother was out in the middle of nowhere. In fact, it was no more than twenty-five feet away from the door of the next house. And across the street from a church. It was a street filled with houses. There’s no way that people didn’t know something was going on. Between that and the fact that Florida’s Department of Children & Families had come twice to the apartment where she lived when she was younger—two and three years old—and just left her there. Had they intervened then, it would be a far different story. She would probably be able to talk now.

What really struck me, too, was what the doctor at the university who examined her first said: how rare it is to find a child Dani’s age that neglected because most kids that neglected are either found by human services earlier, or they die. Because they have no contact. Like orphans in Romania who die in their cribs. So I think it’s a real tribute to Dani that she lived to six years old until she was finally rescued from that place.

I looked in the window where she was kept, and it was the size of a closet. And she was kept there day after day after day. This wasn’t included in the book, but I saw the police photos from the day she was taken, and it was enough to make you sick to your stomach. The social worker who had gone in first that day before the police arrived—she was the one who was outside vomiting when they got there.

Chapter 16: What brought you to the story in the first place?

West: A visit to the Acklen Avenue Post Office, to be quite honest. Bernie and Diane Lierow were living in Florida when they adopted Dani, but they had lived in Tennessee before. Bernie had done beautiful carpentry work for Bob Oermann that I had always admired. He had done all of the cabinets for all of Bob’s trillion vinyl albums. When Bernie and Diane were being inundated after that newspaper story, they didn’t know what to do, so they got in touch with Bob. All of these people wanted to do books. So Bob’s agent became involved, and they wanted Bob to do it, except he was involved in a project at the time. So, literally, I was walking into the Acklen Avenue Post Office, and he was walking out, and he said, “You have to do this.” And I said, “Do what?” And he explained the story to me. It was sort of like a blind date.

Chapter 16: Was it difficult to write the story in Diane’s voice, and what was that process like?

West: My original proposal was to write it with a journalistic treatment, but every publisher, without exception, came back saying it had to be first person, the voice of the mother. When the agent was coming back to me saying this, she got all snappy with me. She said, “You just ask Bob Oermann. For crying out loud, he wrote Brenda Lee as Brenda Lee!” So I’m like, “Well, geez, if Bob can write Brenda Lee as Brenda Lee, I can do this.” A few days later, I ran into Bob, and he was like, “Are you kidding me? That was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. It was miserable!”

So the way we did it was I basically became Diane. I spent days and days with them and Dani. I didn’t spend the night, but I would get there at five in the morning so I could be there for the morning routine. And I stayed there all day. I went to school with Dani and talked to her teachers. I babysit many nights. I had some uniquely Dani experiences. I went to church with them, I went trick-or-treating with them, I went to the Wilson County Fair with them.

So the way we did it was I basically became Diane. I spent days and days with them and Dani. I didn’t spend the night, but I would get there at five in the morning so I could be there for the morning routine. And I stayed there all day. I went to school with Dani and talked to her teachers. I babysit many nights. I had some uniquely Dani experiences. I went to church with them, I went trick-or-treating with them, I went to the Wilson County Fair with them.

Chapter 16: What might you have done differently if you’d written it from the point of view of a reporter?

West: The Lierows have this fear of Dani being taken away from them. I probably would have been more critical of child services and the biological mother. I think a third party can be just as powerful telling the story as someone in first person. But that said, I would write three chapters and give them to Diane, and Diane would read every word. She would give me back the chapters and say, “This isn’t exactly right,” or “I’d rather say it this way.” So even though I did all the writing, Diane vetted every word and changed some things around. It’s very much Diane’s story.

Chapter 16: Knowing you as I have for years, I’m guessing you’re pretty attached to Dani and she to you. Do you suppose you’ll have a connection to the Lierows always?

West: Yes, I believe I will. I’ve seen them several times since the book was finished, we keep in touch, and I’ve offered to babysit. It’s an open offer. The first time I met Dani she reached out her hand to me when I was leaving, and Bernie and Diane said that was very unusual. The second time I came, I brought my Best Ever Chocolate Chip cookies, and did the next couple times, too, so she came to look for the cookies every time she saw me. I’m not exactly a country girl, as you know, so driving out to the far end of Wilson County and coming home smelling like a barnyard is not my favorite thing, but everyone who meets Dani falls in love with her, and I’m no exception.

Chapter 16: Why was it important to the Lierows to tell their, and Dani’s, story?

West: They told their story for one reason: to encourage others to try foster care and adoption. When the paper first proposed the story, it was for a Valentine’s package, and they agreed only for that purpose. They felt very grateful to the Heart Gallery for connecting them to Dani. Diane and Bernie can reel foster-kid stats off the top of their heads, and it’s an issue near and dear to them both. When Diane talks about kids in foster care, she gets visibly emotional. So they did it to raise awareness and encourage others to foster and/or adopt. Not necessarily a special-needs kid, but they feel like every kid in foster care is a special-needs kid in some way. You don’t get into the foster system from a happy, healthy, loving family.

Chapter 16: There are few families willing to take in kids like Dani, who are so profoundly in need. What is it about the Lierows that made them so willing to embrace the challenge?

West: I believe part of it is that both of them were only children, and they were both pretty lonely as kids. I think they both like having lots of kids. They’re fostering a couple of other kids right now. They have William, the son they have together. They have Dani, and then they’re fostering two teenage girls.

But as far as Dani—that was a matter of faith. They were not looking for a special-needs child, by any means. They wanted a sibling for William, and they wanted one who was younger than him, who could play, who had been potty trained. They had it all thought out. And then they saw the photo, and they have never wavered in that. They saw the photo and believed it was predetermined. They knew from the moment they saw that photo: she was their child.