Means of Survival

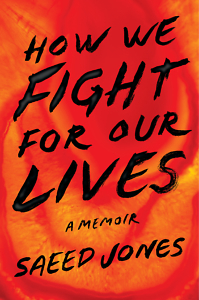

Saeed Jones’ memoir delivers a portrait of the artist as a young gay black man

Early in his memoir How We Fight for Our Lives, award-winning poet Saeed Jones recalls huddling in his bed at age 12, acutely aware of both his vulnerability to racist violence and his own capacity to do harm. “Just as some cultures have a hundred words for ‘snow,’” he writes, “there should be a hundred words in our language for all the ways a black boy can lie awake at night.”

How We Fight for Our Lives follows that frightened 12-year-old boy into young manhood, as Jones struggles to find a way to be fully himself — black, gay, an artist in love with language — in a world that doesn’t readily provide a place for him. Written in 21 short, episodic chapters, the book is as intense as a dream or a nighttime spiral of obsessive thought. The memoir of a still-young man (Jones is 33), it has a startling energy and immediacy. Nothing in it seems softened by time.

Jones, the only child of a single mother, was born in Memphis and grew up in Lewisville, Texas, a suburb of Dallas. His mother, Carol, was a practicing Buddhist who dealt with the enormous pressure of being sole parent and breadwinner by doing a lot of chanting. In Jones’ loving portrait, she comes across as profoundly devoted to her son, though chronically weary and worried, and her devotion is returned. Their relationship, including Jones’ struggle to come out to Carol and, later, to deal with her dire illness, provides the emotional grounding of the book.

The warmth and acceptance Carol gave were not mirrored outside their small home: not by the white childhood friends who taunted Jones with a homophobic slur, nor by his devoutly Christian grandmother back in Memphis who condemned him at age 13 as “worldly.”

The messages he received from the wider culture weren’t just cruel or harsh; they were terrifying. That wakeful night he experienced at 12 was caused by watching the news coverage of the murder of James Byrd, a black man who was dragged to death by a trio of white supremacists in Jasper, Texas, in 1998. Just a few months later, Jones took in the horrific news about Matthew Shepard, a young gay man who was beaten, tied to a fence, and left to die in rural Wyoming. The two events became linked in his mind, haunting his private thoughts: “Being black can get you killed. Being gay can get you killed. Being a black gay boy is a death wish.”

The messages he received from the wider culture weren’t just cruel or harsh; they were terrifying. That wakeful night he experienced at 12 was caused by watching the news coverage of the murder of James Byrd, a black man who was dragged to death by a trio of white supremacists in Jasper, Texas, in 1998. Just a few months later, Jones took in the horrific news about Matthew Shepard, a young gay man who was beaten, tied to a fence, and left to die in rural Wyoming. The two events became linked in his mind, haunting his private thoughts: “Being black can get you killed. Being gay can get you killed. Being a black gay boy is a death wish.”

The road away from that place of fear took Jones through some troubling experiences, including a series of sexual encounters that ranged from disappointing to dangerous. He writes about this aspect of his life with sharp honesty, acknowledging his own occasional cynicism, as well as his need and vulnerability. The pursuit of gratification, in this telling, is one of the ways he fought for his life — that is to say, for the right to walk through the world authentically and unapologetically — even though it did on one occasion involve a literal fight to save himself.

Through it all, Jones was writing and reading, finding sustenance, if not always consolation, in the words of writers like Reginald Shepherd, a gay African American poet who died at 45. Jones recalls how a line of Shepherd’s — “My aim is to rescue some portion of the drowned and drowning, including always myself.” — sent him into a momentary despair, deepened by a memory of trauma. But just as words awakened pain, they also served as a means to conquer it:

Sitting back down in front of the pile of books, I returned to Reginald Shepherd’s words: he was gone but they were still here. I thought about all the poets who kept me going, one more minute, one more step. For the drowning and the drowned. I felt the cord pull taut between us. I took a breath. I started a draft of a new poem.

His will to create would eventually garner Jones ample literary recognition, including a slew of awards for his 2014 debut poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise. A stint as one of the hosts of Buzzfeed’s AM to DM talk show on Twitter has also given him a kind of visibility few young poets enjoy. How We Fight for Our Lives, which ends in 2011, delivers a powerful, sometimes disturbing backstory to all that success; and yet it’s not so much a counterweight as a full accounting of Jones’ gifts — for language, for love, and for survival.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Still, Hippocampus, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She is the editor of Chapter 16.