Meeting Aunt Z

A memorable first encounter with Tennessee

Our visit to an uncle I’ll just call K was complicated by his living arrangements.

He had bought, sometime in the past, the house next door for his wife, whom I’ll call Aunt Z. It was less scandalous than divorce, and cheaper, and anyway the arrangement worked out well enough since every week or so Uncle K would leave his laundry outside on his back stoop and Aunt Z would return it there a few days later, washed and pressed just the way he liked it. She also cooked his meals, or some of them, leaving them on that same back stoop and coming back later to get the dishes. Uncle K got to be a good provider, as men were supposed to be then, and Aunt Z got to be a good wife. Best of all, they never had to see each other.

I first got the gist of this story sitting in the back seat of my father’s Cadillac as we threaded our way through residential streets somewhere in Nashville on our way to see Uncle K and Aunt Z. I was 5. It was my first trip to Tennessee, my father’s home state, and also my mother’s first trip, since my father had not mentioned when he married her that he had any family at all. In fact, he had quite a lot of family — in addition to his brother, Uncle K, he had a gaggle of other older brothers and one sister, all of whom had grown up in Dickson County. I was his late-in-life daughter, born as he neared 60, so my aunts and uncles were in their 70s and 80s.

As soon as we turned on their street, my father faced a dilemma. He didn’t want to park in front of Uncle K’s house, for fear of offending Aunt Z. Nor did he want to park in front of Aunt Z’s house, for fear of offending Uncle K. “There’s the two houses,” he told my mother, raising one finger off the steering wheel to point. They looked ordinary enough — two small houses side by side, about the size of our house in Oklahoma City. My mother, whose gift for detachment rivaled an anthropologist’s, said nothing I remember.

My father had probably not called first, so most likely neither Uncle K nor Aunt Z knew we were coming. The Cadillac, a hulking green model from the late 1950s, was hard to hide in a neighborhood filled with Fords and Chevys. He slowed to a crawl, threading his way between the cars parked on either side of the street, then drove to the end of the block, turned the Cadillac around, and parked across from both houses in neutral territory. He cut the motor. My mother started to get out but he just sat there, deciding where to go first. He said we’d better start with Aunt Z. I’m not sure why. He had a chivalrous streak, so it may have been that. Or it may have been the fact that Uncle K’s drapes were shut tight so he probably hadn’t seen us, while Aunt Z’s were open and she probably had.

Aunt Z did not look remarkably different from the other Tennessee aunts I met that summer. They were all neat, plump ladies with floral dresses and boxy shoes, their gray waves pulled up in thin hairnets. But I immediately liked her. After the initial surprise when she saw my father, she welcomed us into her living room, a bright place with knick-knacks in glass cases and antimacassars on the backs of chairs. It was extremely clean. Sitting next to my mother on an overstuffed couch, I followed the line of the hardwood floor all the way to the edge of the wall. I had heard somewhere the phrase “so clean you could eat off the floor.” I remember thinking that was true. Unlike our house, it had not a single dust bunny.

I don’t remember what the adults talked about — probably what my father had been doing since his last visit and all about my mother, who was still in her forties and worked as a secretary. Aunt Z cooed over me a bit, as had the other aunts and some of the female cousins old enough to be my aunts. Later I learned it wasn’t all that unusual for my father to turn up every few years with a new wife, but a new daughter was rare. I was younger than his own grandchildren, though I’m not sure I knew that yet.

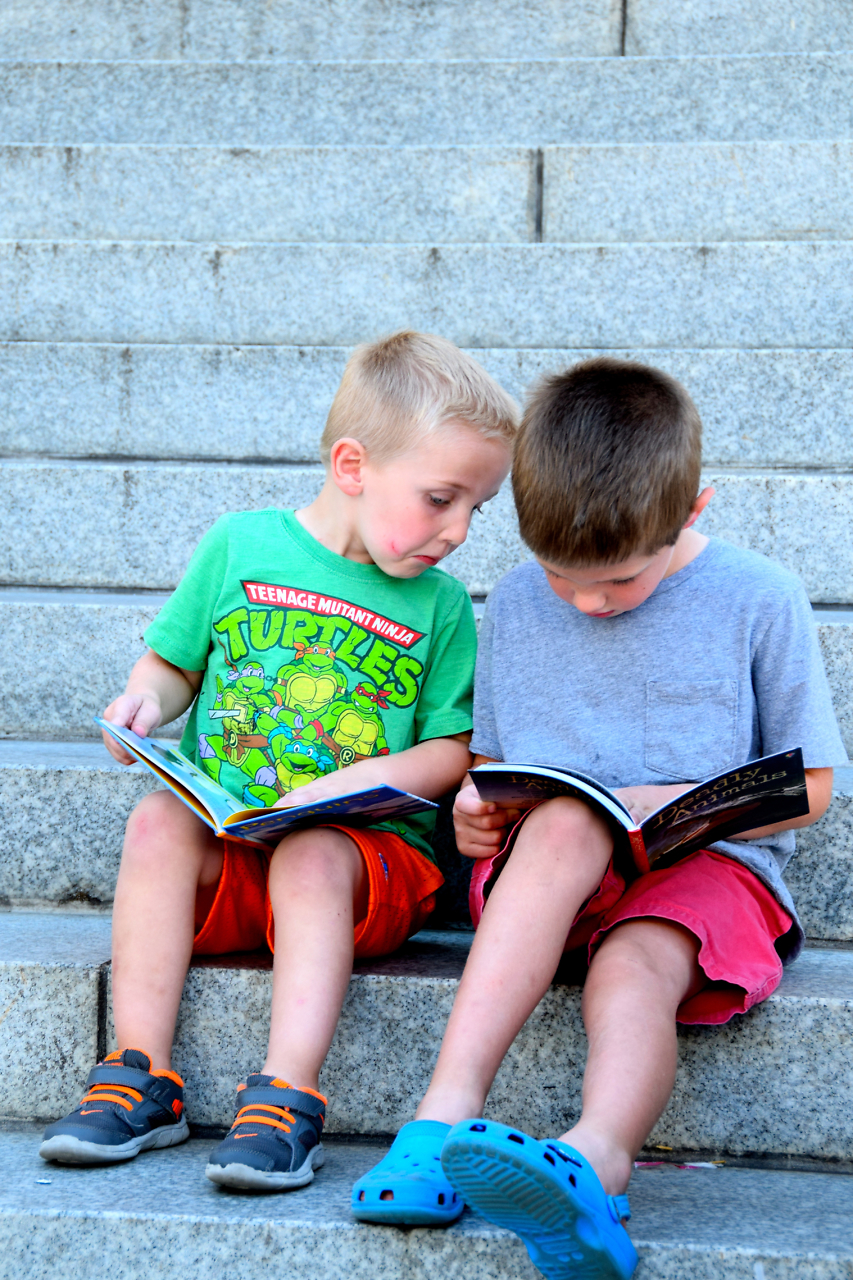

After we sat there a few minutes, Aunt Z asked if I would like to help her in the kitchen. She had put on a pot of coffee when we first came in and said I could help her carry a tray of cookies. I wasn’t too sure about this. Tennessee was new territory, and I had stuck close to my parents in the few days we’d been there. But my mother nodded, so I followed Aunt Z through a darker middle room toward the back. The kitchen was as bright as the front room and as clean. I marveled at the gleaming chrome, the spotless white tiles and porcelain, and the pots and dishes, all from another era.

There was a splotch of red somewhere in that kitchen. I don’t remember now what it was. It might have been the tablecloth or curtains that edged the big window. It might have been a dish or an apple. But I remember vividly the color red, a detail I’ve carried across decades. It fixed my attention, surprised me somehow. I wanted to stay in that room, there in the clean, bright past to see what I could understand about this place, Tennessee, that I was not only in but of, and this aunt, one of my father’s ancient relatives, someone from his life before me, which I could never fully know. I didn’t think that in so many words, of course, but I had a child’s instinct — questions that came before words. All this happened quickly. Then Aunt Z handed me the tray of cookies and said to hold it carefully, and I followed her back to the room where my parents waited.

After a while, as the four of us sat there, the grownups balancing the china cups on their knees, Aunt Z leaned forward and said to my father, almost in a whisper, “How is he doing? Have you been over there?” She meant Uncle K, of course. She wanted the brother-in-law she rarely saw to tell her about her husband next door. It took my father a moment to grasp what she meant, and then he said no we hadn’t been yet, and she said, oh, oh, of course not, her words fluttering up like so many small birds. There was a silence then. My mother, who was kind, may have filled it with some remark — that the coffee was good, that Tennessee sure was hilly compared to Oklahoma. In a little while, my father set his cup on the table and said we should go.

Uncle K’s house was dark, with a closed-up smell. He sat in the front room in a big chair pulled to the center, a small table next to it, magazines stacked all around. For years, needing him to have been sophisticated, I remembered him in a smoking jacket, but it was probably a bathrobe he wore while smoking. He offered me a Coke, which I refused. It seemed dirty somehow, because his house was. That moment stays with me — my small childish cruelty toward an old man and how it embarrassed my father.

Much later I heard the story about how my father and Uncle K’s sister’s husband, a postman, delivered mail on the route where Uncle K’s lady friend lived. That’s what they called her — the “lady friend.” One afternoon Uncle K heard him coming and tried to hide under a piece of furniture, but the brother-in-law saw through the open window. This would have been long ago, before air conditioning. The brother-in-law said to come out — that he’d know those big feet anywhere. But Uncle K said he loved the lady friend and would not give her up, and Aunt Z said she would not have a divorce. That’s how they came to live in two houses.

We went to Tennessee most years after that, but I don’t remember going back to those houses. Maybe my father went alone. I don’t know. He never mentioned that day we were there, and I never again saw Aunt Z.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Jane Marcellus. All rights reserved. Jane Marcellus’ essays have appeared in journals including Gettysburg Review, Syracuse Review, and Hippocampus. She received the New Ohio Review Editors’ Prize in 2019. She is a professor at Middle Tennessee State University.