Mirror Images

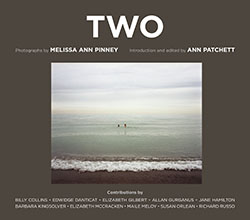

Two, Melissa Ann Pinney’s new collection of photographs, captures pairs of all kinds

Two by Melissa Ann Pinney, a photography collection paired with personal essays edited and introduced by Ann Patchett, explores pairings of all sorts: couples, doublings, twins, and reflections. The book offers a wide spectrum of takes on pairs in both human subjects and landscapes—from the twin cupolas of a foggy, eerily lit playground structure at night to a mother reverently embracing an infant. “We’ve all heard stories of people who find their heart’s desire the minute they stop looking for it,” writes Pinney in a preface. “What I found when I wasn’t looking were pairs of every manner and kind.”

These are some of the moments captured in Two:

These are some of the moments captured in Two:

A child sprawls on a bed before a sheer-curtained window, lifting her hands, fingers spread wide, to the sky.

A woman, her lips glossed pale pink, places a plastic tiara atop a young girl’s head.

Two boys in dress clothes, their backs to the viewer, peer out of a hotel window to the world far below.

Two has something of a charmed origin, as book birthings go: it was shepherded into its final form with the help of Pinney’s close friend Ann Patchett, novelist and co-owner of Parnassus Books in Nashville. In an introduction, Patchett writes about her own appreciation for Pinney’s work—she’d seen the images in progress, tacked up on the walls of Pinney’s New York studio—and then acknowledges considering the photographs as a bookseller: “From the first time I saw Melissa’s pictures, I found myself thinking about how to get this book into the hands of people who would want to find it,” she writes. Her solution: to commission brief essays which could be interlaced with the images “to make their own sort of two, not so much a collaboration as a reinforcement.” Being Ann Patchett, she had quite the Rolodex to work from: authors like Elizabeth Gilbert and Susan Orlean, Barbara Kingsolver and Billy Collins (who contributed a poem), Allan Gurganus and Elizabeth McCracken, among others.

The resultant pairing of image and text is a model well worth replicating. Why not make books that comprise images and text on a single theme? Why not have them sit shoulder-to-shoulder instead of insisting that one serve the other—a book where words aren’t captions, and images aren’t illustrations?

The resultant pairing of image and text is a model well worth replicating. Why not make books that comprise images and text on a single theme? Why not have them sit shoulder-to-shoulder instead of insisting that one serve the other—a book where words aren’t captions, and images aren’t illustrations?

When Kingsolver shares a bittersweet meditation on her parents’ fierce attachment to one another (“It’s the most senseless of all wishes: they never should have had me”), we are not distracted from Pinney’s images, nor does Kingsolver’s essay attempt to cast the images that come before and after it in a new light. Her contribution to Two is a discrete piece of art. Each photograph and each essay is connected to the rest only by theme.

Not that theme isn’t more than enough connective tissue. Where Kingsolver, Orlean, and the rest of Patchett’s all-star cadre of scribes tell stories with words, Pinney’s images achieve a similar narrative end: in most, a hidden story could be said to draw one into the frame, to leave one lingering there. These photographs are replete with silences the viewer cannot help but try to fill. A photograph of two people implies a dialogue, a communication of some kind, however fleeting or static-laden. A history, a present, a future: the stuff of story.

Musing on the capacity for solitude required of writers, Patchett notes, “Somehow, it’s my ability to be alone that attracts me to these images of pairs, in the same way that Melissa, alone behind her camera, sees the twosomes in the world around her. Those of us who are best at solitude marvel at the easy comradery of two sisters, two lovers, two cups balanced, one inside the other.”

True. And yet these pairs don’t always read as evidence of intimacy or symbiosis. Some of Pinney’s best shots express not ease but tension. Sometimes it’s the friction or disconnect between two subjects—a young woman cutting the hair of a wheelchair-bound older man, her cleavage a visual echo of his bare, tanned legs and the scar running the length of his left knee—that lures the eye. But always, it’s the story murmured beneath the surface.

Susannah Felts is a writer, editor, and educator in Nashville, as well as co-founder of The Porch Writers’