More Than a Footnote

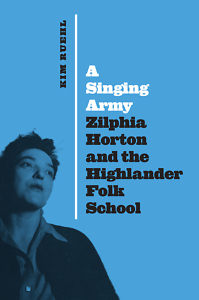

Kim Ruehl explores the life of activist Zilphia Horton in A Singing Army

Long before former No Depression magazine editor Kim Ruehl wrote A Singing Army: Zilphia Horton and the Highlander Folk School, she noticed a recurring pattern in historical accounts of the training center for labor and civil rights activists founded in Monteagle in 1932.

“It was always Myles, Myles, Myles,” she said in a panel discussion at the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University in April, referring to Myles Horton, Highlander’s founding director. “That’s how we tell history. There’s this one hero at the center, and he has this idea, and the world bends to it.”

“It was always Myles, Myles, Myles,” she said in a panel discussion at the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University in April, referring to Myles Horton, Highlander’s founding director. “That’s how we tell history. There’s this one hero at the center, and he has this idea, and the world bends to it.”

As Ruehl sees it, Highlander’s history is “about a community of people” who built the school together despite prevailing gender norms and Jim Crow racism during the Great Depression. And Zilphia Johnson Horton, who came for a workshop, married Myles, and put music at the core of Highlander’s curriculum, was “all about collaboration.”

“Zilphia is usually included as little more than a footnote, her innumerable contributions distilled to nameless descriptions of the school’s ‘spirit’ and ‘atmosphere,’” Ruehl writes. But the young woman from Paris, Arkansas, who arrived in Monteagle in 1935 — fresh from an argument with her mine-boss father and eager to change the world — becomes far more intriguing in Ruehl’s account. The oldest of four daughters who hailed from a strong matrilineal line, she earned a music degree from the College of the Ozarks, then played piano during silent movies before teaching high school in Sallisaw, Oklahoma. That job went well until she called the biblical story of Jonah and the whale a metaphor. “She wasn’t exactly fired,” Ruehl writes, “but it was suggested that she go home.”

Back in Paris, Zilphia met Claude Williams, a Tennessee theologian with radical ideas about social justice. Enthralled, she signed up for a workshop at Highlander run by Williams’ old friend, Myles Horton, and stayed the rest of her life.

A Singing Army tells many stories. One is about a young woman’s independence in an era when gender roles were contested but even career-minded women were expected to quit their jobs upon marrying. Zilphia married Myles just three weeks after meeting him, but the impromptu wedding, officiated by a minister from Soddy-Daisy they had met at a labor strike, marked the beginning of her career, not the end. She ignited in Myles “the kind of fire he possessed” and as culture director of Highlander became his professional partner, calling on her musical talent and studying theater in New York to incorporate the arts into the center’s work. Both wanted an egalitarian marriage, which she called in a letter to him “the freedom of two personalities made richer by the blending of their complements and supplements.”

Some of Ruehl’s book explores the Hortons’ domestic life. They welcomed two children, Thorsten and Charis, and befriended locals, although some in the conservative community thought, erroneously, that they taught communism. Committed to racial integration, they hosted, among others, Rosa Parks in 1955. The U.S. State Department brought foreign diplomats to Highlander, a rare place in the South where dignitaries from African nations could stay comfortably.

Some of Ruehl’s book explores the Hortons’ domestic life. They welcomed two children, Thorsten and Charis, and befriended locals, although some in the conservative community thought, erroneously, that they taught communism. Committed to racial integration, they hosted, among others, Rosa Parks in 1955. The U.S. State Department brought foreign diplomats to Highlander, a rare place in the South where dignitaries from African nations could stay comfortably.

But most of A Singing Army explores Zilphia’s conviction that music should go beyond “art for leisure.” Folk songs, she wrote, arise “out of reality — out of the everyday lives and experiences” of people, giving them “vitality and strength.” As such, music became central to labor organizing workshops at Highlander and its civil rights work. Zilphia inspired many who spent time there, including Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. After Highlander, Guthrie “was preoccupied with the idea of writing union songs.” Seeger heard the song then called “We Will Overcome” in Zilphia’s rich alto after she learned it from a Black woman, Lucille Simmons, during an American Tobacco strike. Seeger changed “Will” to “Shall,” preferring “the way a ‘sh’ sound pulled the rhythm forward, the … letter ‘a’ opened up the singer’s mouth.”

A Singing Army is thoroughly documented, drawing on archival research, letters, and interviews with Thorsten and Charis, Zilphia’s sister, and others. As portrayed by Ruehl, Zilphia is independent, resourceful, resilient, and original, and Myles clearly shares her collaborative spirit. Although “social justice” and “the South” are still often seen as oxymoronic, Ruehl illuminates a time and place when people were trying to make them synonyms.

Zilphia’s accidental death from poisoning in 1956 marked the end of an era. The school remained open at Monteagle and Myles eventually remarried, but allegations of communism continued. Despite Highlander being cleared in an FBI investigation, the state revoked its charter and confiscated the property in 1962. It reorganized as the Highlander Research and Education Center near Knoxville.

Ruehl says Zilphia’s collaborative spirit continues, though, with songs she taught still familiar to young people and sung by social movements everywhere.

Jane Marcellus is a professor at Middle Tennessee State University, where her research has examined media representation of employed women in the 1920s and 1930s. Her essays have been listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays 2018, 2019, and 2020.