Mountain Meanderings

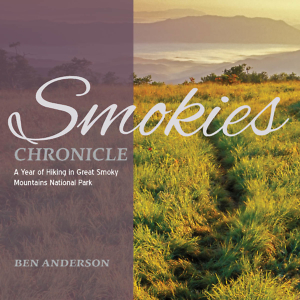

Ben Anderson chronicles a year in the Smokies

At sixty-four, Ben Anderson spent the year after his retirement not with his feet up on the porch rail but with his boots on the ground, hiking the Great Smoky Mountains National Park’s most rewarding back-country trails. In his new book, Smokies Chronicle, he chronicles the hikes he made on trails he already knew intimately from more than twenty years as a volunteer custodian of backcountry campsites, cleaning up litter and knocking down illegal fire rings.

Anderson’s 2016 project, to hike three or four trails each month, was something more than a job. Anderson lives in Asheville, North Carolina, and he takes to the mountains like a lover, following his heart into the primal remnants of old-growth yellow poplar, along trails thick with spring beauties, onto rocky cliffs with 360-degree views of the mist-cloaked ridges, or to the foot of plunging waterfalls on the park’s iconic prongs and forks.

Anderson’s 2016 project, to hike three or four trails each month, was something more than a job. Anderson lives in Asheville, North Carolina, and he takes to the mountains like a lover, following his heart into the primal remnants of old-growth yellow poplar, along trails thick with spring beauties, onto rocky cliffs with 360-degree views of the mist-cloaked ridges, or to the foot of plunging waterfalls on the park’s iconic prongs and forks.

With more than 11 million visitors in 2016, the centennial of America’s National Parks system, the Smokies are well known, perennially the most visited park in the United States. But despite heavy use, the Smokies’ more than half-million acres are still in many places nearly pristine. Once off the heavily traveled Appalachian Trail, hikers can still a spend day in the woods without seeing another soul.

Smokies Chronicle takes readers onto forty of those trails, each described in Anderson’s mild and modest commentary. He recounts the flowers and views and trail junctions he encountered on each hike, but he also recalls earlier treks along the same route—memories of his sons’ childhoods and the times he stood with his wife at a particular lookout. He provides insight into the history of the region before the park was created, a time when it was almost clear-cut by timber companies. Some of the trails follow old roadbeds and railroad right-of-ways, or pass preserved houses and cantilevered barns.

Anderson notes the family cemeteries now hidden deep in the forest, remnants of the Southern Highlanders that park advocate Horace Kephart describes in Our Southern Highlanders, his seminal work on the mountain people eventually displaced by the park and a changing economy. “But the backcountry’s most prominent and poignant reminders of human habitation are the scores of cemeteries that remain inside the national park,” Anderson writes. “In some cases, the gravesites are starkly marked by fieldstones, revealing no names or dates. The cemeteries, totaling more than 150 according to park archives, provide evidence that the Smokies have largely returned to wilderness only within the past century.”

Over the course of the year, Anderson traversed the park’s most iconic trails in the Greenbrier, Deep Creek, and Cataloochee areas, where a large herd of elk has been re-established. He climbed every still-standing fire tower and looked out from Rocky Top itself. He chatted with other backpackers and day hikers but always sought out solitude and contemplation, noting the birds, the wildflowers, the sky, and the animals, from red squirrels to feral hogs (the now 12,000 descendants of a dozen Eastern European boars imported by a wealthy landowner in the early twentieth century).

Over the course of the year, Anderson traversed the park’s most iconic trails in the Greenbrier, Deep Creek, and Cataloochee areas, where a large herd of elk has been re-established. He climbed every still-standing fire tower and looked out from Rocky Top itself. He chatted with other backpackers and day hikers but always sought out solitude and contemplation, noting the birds, the wildflowers, the sky, and the animals, from red squirrels to feral hogs (the now 12,000 descendants of a dozen Eastern European boars imported by a wealthy landowner in the early twentieth century).

But the most dramatic story of 2016 in the Smokies was presaged almost from the beginning of the year, when Anderson first noted the unusual drought. Throughout the year he mentions the low streams and the tinder-dry conditions. In autumn he notes the sky paling from blue to gray, not from clouds but from the smoke of wildfires throughout the region. Finally, on November 28, the Chimney Tops fire that had been smoldering for weeks, forcing a parkwide ban on fires, erupted.

“Fed by dry vegetation, low humidity, and winds gusting to hurricane force, the Chimney Tops 2 Fire ultimately grew exponentially from a two-acre blaze on the Chimneys’ northern spire,” Anderson writes. “The fast-moving fire raged far beyond a planned four-hundred-acre containment area to become a catastrophic eighteen-thousand-acre inferno inside and outside the park. … In short, the fire’s impact inside and outside the park was historic, devastating and deadly, as it killed fourteen people and injured or sickened nearly two hundred more. Gatlinburg and Sevier County will never be the same after a truly hellish night.”

Smokies Chronicle is modest in scope and style. It includes almost no photographs and only rudimentary mapping, but the book doesn’t claim to be a trail guide. Instead, its intimate essays capture the essence of the park and awaken the desire to follow Ben Anderson into the primeval forest.

Lyda Phillips is a veteran journalist who grew up in Memphis and has earned degrees from Northwestern, Columbia, and Vanderbilt universities. The author of two young-adult novels, she worked for United Press International before returning to Nashville.