Mr. On the Way Up

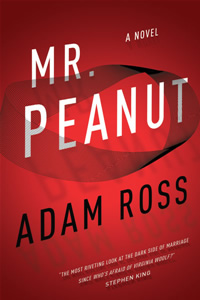

Chapter 16 talks with Adam Ross about the most talked-about debut novel of the year

Mr. Peanut, the debut novel by Nashville writer Adam Ross, doesn’t officially hit shelves until today, but the buzz about it has already shifted to an all-out roar, with the normally-terror-inducing Michiko Kakutani herself heralding the arrival of “an enormously talented” and “audacious new writer” in today’s New York Times. And Jonathan Cape, a Random House UK imprint, leaked word via Twitter that none other than Scott Turow will sing the book’s praises in the Sunday New York Times Book Review, apparently calling it “a brillant [sic] powerful memorable book.”

But no one needed the Queen of Mean—the Times review, though rhapsodic in places, is also full of caveats—or a mega-bestselling author of thrillers to tell them this thing was going to be big. The rumbling started back in the winter, when Knopf announced—in an open letter to booksellers by legendary editor Gary Fisketjon, no less—that it would launch Mr. Peanut with a print run of 60,000 copies, and that the book would be published in fourteen countries and in nine languages. The official pre-publication reviews soon joined the throng of wowed book bloggers who already recognized an astonishing new voice: Publisher’s Weekly called it “an inspired debut” and a “unique book—stark and sublime, creepy and fearless—that readers into the darker end of the literary spectrum won’t want to miss.” Kirkus Reviews called it “an intellectual noir novel that shows evidence of an original voice,” noting that “readers that ride out this unsettling head game to the end will find their time well-spent.”

Then, of course, there was that great, booming assessment from the Mount Olympus of Murder, Stephen King’s pronouncement that Mr. Peanut is “the most riveting look at the dark side of marriage since Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” He went on to add, not incidentally. “And it induced nightmares, at least in this reader. No mean feat.”

So if this book worms its way under your skin like some botfly larva, swelling into unthinkable thoughts that demand confrontation anyway, you can’t claim you weren’t warned. Mr. Peanut is the story of David Pepin, a man who may or may not have murdered his wife, Alice, through forced peanut ingestion, but to call this book a crime novel would be to miss almost everything about it that is unique. Woven throughout the nonlinear narrative of the Pepins’ tragic marriage are the equally compelling, equally disturbing tales of the two detectives investigating Alice’s death: Ward Hastroll, whose own wife has developed an inexplicable and increasingly maddening refusal to leave her bed; and Sam Sheppard, an imaginative extension of the historical Sam Sheppard, who spent ten years in prison for murdering his wife before being exonerated on appeal.

Chronic missteps and fatal misunderstandings form the unstable groundwork of all three interlocking marriages, but Ross isn’t content with this tour-de-force plunge into the heart of marital darkness. The book’s original narrative structure is equally challenging, an Escher-like set of subtle repetitions and repercussions that shift in significance depending on the angle from which they’re seen. This is a page-turner, no doubt, but figuring out whodunit soon ceases to be the primary point. The combination of character and structure works to force much bigger questions: what does any of us truly know about the people we love? Or about ourselves?

Chronic missteps and fatal misunderstandings form the unstable groundwork of all three interlocking marriages, but Ross isn’t content with this tour-de-force plunge into the heart of marital darkness. The book’s original narrative structure is equally challenging, an Escher-like set of subtle repetitions and repercussions that shift in significance depending on the angle from which they’re seen. This is a page-turner, no doubt, but figuring out whodunit soon ceases to be the primary point. The combination of character and structure works to force much bigger questions: what does any of us truly know about the people we love? Or about ourselves?

Mr. Peanut launches today with a public reading at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville. If the pre-publication response is any indication, it will be followed by an avalanche of reviews and a barrage of discussion—and vehement argument—among readers. Before all that, Adam Ross (whom—full disclosure—I first met when we were both columnists for the Nashville Scene) took time to answer some questions by email.

Chapter 16: Before I even get to the book, I have to ask: were you ready for your life to change? Because what’s happening to you right now, apropos though it may be to this particular novel, really only happens in the movies or maybe in the dreams of MFA candidates. There’s no way you can come out of a shocking experience like this unchanged, is there?

Ross: The answer to the first question: You’re never ready for your life to change. As Ward Hastroll observes in the novel, “We have our backs to the future,” even if that future is something we’ve dreamed of for years. It’s always different. To give you one example, I haven’t been prepared for the amount of time being an author requires in the run-up to publication, as opposed to the time one needs, daily, to be a writer. If that sounds like a complaint, it isn’t at all. It’s been a blast. I just got back from Chicago where I had lunch and dinner with all these great independent booksellers who loved the novel, and they’re all brilliant, eclectic, unbelievably well-read, passionate people who eat, drink, and sleep books. This is change I can believe in.

To answer the second question, however, the initial “shock” of the experience came when Gary Fisketjon and Sonny Mehta [at Knopf] made the offer on Mr. Peanut and my book of short stories, Ladies and Gentlemen, which was followed by European publishers jumping in. I was teaching at the Harpeth Hall School at the time, and I walked around in an absolute daze for a good, oh, two months. But even more noticeably, this little voice in my mind—this cheerleader I’ve had rooting me on since I started these projects—fell over dead from exhaustion. Her job was done. I enjoyed that surge of confidence, elation, and vindication, and then I cracked my knuckles and thought, “OK, time to get back to work.” Because the meaning of all this is the same thing, I’m guessing, that it would be for any aspiring writer: thank you, God, now I have time to write.

Chapter 16: During your years in Nashville, you’ve been a bartender, newspaper editor, and middle-school teacher. Till now, despite earning two advanced degrees in creative writing, you have been entirely unknown to the anointed literary set. What kind of welcome, if any, have you had from the rest of the state’s writers? When you say, “Hi, Ms. Patchett,” on your morning run, does she recognize you?

Ross: I have no idea if she does. I have a hat and sunglasses on, it’s always early, and I’m really sweaty by the time I get to her street, so I’m guessing when this strange guy goes chugging by and says hello, she either thinks, “Damn, I wish I had a Doberman,” or “Ah, my public.”

Ross: I have no idea if she does. I have a hat and sunglasses on, it’s always early, and I’m really sweaty by the time I get to her street, so I’m guessing when this strange guy goes chugging by and says hello, she either thinks, “Damn, I wish I had a Doberman,” or “Ah, my public.”

I have become friends with Amy Greene, the East Tennessee author of Bloodroot—whose book I’m nearly finished with and loving. We’ve corresponded about pre-publication/tour stuff, as well as each other’s books.

Here in town, I’ve had several encounters with Tony Earley over the years. When I was at the Scene, I tried to get him in the swimsuit issue (he declined), then we played a round of golf together at Harpeth Hills (a second attempt to get him into the swimsuit issue, which failed as well). Years later, I had him to Harpeth Hall to read from The Blue Star. In fact, last Thursday, after saying hello to Ms. Patchett on my run that morning, I ran into Earley at Five Guys. Mr. Earley and I had a very, very serious talk about his round. Oh well, so much for the New New Agrarian movement.

Chapter 16: The impulse, with a story like yours, is to think of the writer as an overnight success. You’ve never written a novel before, have published only the smallest handful of short stories, and yet suddenly here you are—on NPR, in The New York Times, etc. In reality, you started work on this novel in 1995, fifteen years ago. Did you, like David Pepin, have trouble figuring out where the story should go? (“But the middle, David wrote, is long and hard.”) Or did you simply have too little time, between work and marriage and, later, fatherhood, to write?

Ross: My answer is tautological: the novel took as long as it took to write because it took as long as it took to write. Part of it was the process, the subject matter, my own development as a writer. Part of it was too little time, between work and marriage and, later, fatherhood, to write. But after I was granted time to write—after I got the deal with Knopf—I certainly took full advantage of that gift.

Chapter 16: This is one seriously dark novel, a “police procedural of the soul,” as Knopf editor Gary Fisketjon puts it, a book that’s famously given Stephen King nightmares. I’m curious about Knopf’s decision to bring it out in June. Despite the fact that it hit number-one in the beach-read poll at The Huffington Post, I can’t imagine why anyone would characterize this book as a beach read—I mean, unless they’re just afraid to read it alone at night. What was the thinking behind this timing?

Ross: I think Knopf foresaw the Deepwater Horizon disaster and knew that not only would the beaches of the south- and possibly northeast be ruined but that people in general would be in a dark mood this summer once they were forced indoors. What book, the Knopf strategists thought, goes with economic, political, and environmental turmoil? They looked at their list and said: Ah, Mr. Peanut—a crude and dirty bit of business.

Seriously, though, I think the summer season isn’t only the beach-reading season. It’s also when people have a little more of that most precious commodity of all: time itself. They get to browse their local bookstores more than usual and at a more leisurely pace. A book with a pixilated skull catches their eye. Perhaps someone working the floor says, “Trust me on this one. It’s very macabre and complex. Not for the faint of heart or those who like The Answers served up on a platter. Must be read in BIG CHUNKS. Reader must also have an open mind or find the darker aspects of human relationships fascinating. Also has lots of sex and death, and, if you can believe it, guarded hopefulness.”

Seriously, though, I think the summer season isn’t only the beach-reading season. It’s also when people have a little more of that most precious commodity of all: time itself. They get to browse their local bookstores more than usual and at a more leisurely pace. A book with a pixilated skull catches their eye. Perhaps someone working the floor says, “Trust me on this one. It’s very macabre and complex. Not for the faint of heart or those who like The Answers served up on a platter. Must be read in BIG CHUNKS. Reader must also have an open mind or find the darker aspects of human relationships fascinating. Also has lots of sex and death, and, if you can believe it, guarded hopefulness.”

Chapter 16: The refractive—and reflective—structure of Mr. Peanut creates insistent parallels between characters, even when some of the characters are themselves imaginary within the context of the imaginary world of this novel. Much is being made of what this novel has to say about the nature of marriage, but it also seems to be saying something about the unstable and essentially imagined nature of our own narratives.

Ross: Bingo. I have a very dear friend who had two brothers and a lovely, attentive mother. His brilliant, successful father worked overseas and was often gone for weeks at a time, but when he was home, he was a terrific dad. One day, he announces to the mother, “I have another family in Europe: a woman with whom I’ve a daughter. I can’t participate in this sham of a marriage any longer”—and he left. Needless to say, his wife’s version of their marriage wasn’t his—was utterly shattered—not to mention her entire emotional reality. She literally had no clue. Mr. Peanut uses the idea of the Mobius band to explore this. It’s a surface with one side and one edge that gives the appearance of two-sidedness. In marriage, two people are supposed to exist on the same side of things, but move them along the band of time, and guess what? It can appear as if they’re on the exact opposite.

Chapter 16: I’m guessing that any suggestion of the essentially insubstantial nature of the human soul, any creative evidence that we’re all imaginary constructs within our own understanding of the world, is pretty disturbing to a lot of people. Most of the violence in this mystery happens offstage, but murder most foul isn’t what’s really scary about Mr. Peanut, is it?

Ross: Again, you put your finger right on it. In the Sheppard section of the novel, we spend part of the time in Marilyn’s point of view. She nearly destroys her marriage (and possibly herself) because of a perceived slight by her husband. Ironically, their marriage is subsequently saved by a surprise act of generosity by him, which remedies the former. But as she makes her way through Bay Village, Ohio, that day, furious at her husband about this thing she thinks he’s done to her—something that fits with his history of betrayals—she unwittingly becomes involved with a very disturbed person, who may or may not be the person who kills her. Misunderstandings like that terrify me.

Chapter 16: Here’s a confession: I found these characters intensely compelling, utterly fascinating, but I don’t recognize any of them. These do not feel like my people. I invite you to psychoanalyze this response. Am I too female to get it? Too Southern? Too willing to accept the public fiction of my safe, closed, suburban world?

Ross: I don’t like to psychoanalyze someone interviewing me, but we’ve known each other for a while, Margaret, and so here it goes. At an early age, you discovered that your father kept a rather large bag of peanuts buried deep in his pocket. You checked yours and discovered, to your horror, that you didn’t have any peanuts of your own. Worse, your mother wouldn’t share your father’s peanuts with you, and this made you furious. Through much of your adolescence, you suffered terrible peanuts envy. Not surprisingly, a sensitive person like yourself found expression for these buried, unconscious urges for your father’s peanuts through writing poetry. Thankfully, you got over this neurosis—not the poetry writing but the envy—internalizing your mother’s identity and marrying a terrific man yourself, one who shares his peanuts with you all the time…which explains, in part, why you’ve got so many kids running around your house.

As for the other questions, plenty of females love Mr. Peanut, not to mention female critics. I couldn’t have asked for a more glowing, thoughtful review by Jillian Quint in BookPage or Joanne Wilkinson at Booklist. Or Harvard Bookstore/Bookdwarf.com’s Megan Sullivan, or that talented Morristown writer, Amy Greene. Some women think it gives a window into the male mind. Some women are just fascinated by the vectors of the characters’ fates. Some will throw it across the room. I think the question is whether or not it does what William Gaddis demanded of fiction, which is that it “Bring the news.” You decide.

As for the other questions, plenty of females love Mr. Peanut, not to mention female critics. I couldn’t have asked for a more glowing, thoughtful review by Jillian Quint in BookPage or Joanne Wilkinson at Booklist. Or Harvard Bookstore/Bookdwarf.com’s Megan Sullivan, or that talented Morristown writer, Amy Greene. Some women think it gives a window into the male mind. Some women are just fascinated by the vectors of the characters’ fates. Some will throw it across the room. I think the question is whether or not it does what William Gaddis demanded of fiction, which is that it “Bring the news.” You decide.

Personally, I read fiction, in part, because I get to spend time with people who aren’t my people—Murakami’s people, for instance—and require of these narratives only truth and beauty. Humbert Humbert, for instance, isn’t my kind of people—he’s a pedophile, after all—but he certainly describes obsession beautifully.

Chapter 16: The way married people torture each other is of course the central issue around which all the elements of the story orbit. But in some ways this is a pro-marriage book because you give all of these tormented characters a way out of the torture, and it’s the same way out—simply to stop, as Hastroll tells his wife: “I love you, Hannah. Let’s just step out of the ring!” According to Mr. Peanut, the secret to a happy marriage is to listen, to pay attention, to hang on, to wait out the rough patches. True? Or too “Can This Marriage Be Saved?”

Ross: Yes, true, and yes, it’s a very pro-marriage book. Hastroll’s line comes from Confucius, by the way: “When we do battle with evil, we sharpen evil’s swords.” Good marital and life advice. I don’t know if there’s a secret to a happy marriage, but as Marilyn Sheppard thinks to herself, “Everyone should be lucky enough to be loved for a long time. To know what that was like—to be loved and to change, to be privileged to suffer it, to remain. To know, as she did, that there was only one person she could ever love. To know it incontrovertibly. And accept it, with all of the attendant limits. Once you did, it was the closest thing there was to safety.” I can’t say it better than that.

Every character in this book sees the path to a better place. Then again, like fifty percent of American marriages, they don’t all walk down it.

Chapter 16: On the other hand, the Sam Sheppard character comes to this very realization, and his wife still gets literally tortured, bludgeoned to death at virtually the moment of their reconciliation. (You come very close to exonerating Sheppard outright, though maybe I’m reading too much into the key Eberling hears in the lock.) Are you some old-world authorial god, punishing your characters for taking too long to reach for enlightenment?

Ross: No, absolutely not. For the Sheppards—and only if Dr. Sam was innocent, on which I wouldn’t dare take a final position because we’ll never know—that tardiness is part and parcel of what makes their story so tragic in the novel’s context. His punishment, meanwhile, is a historical fact; he claimed, also, that he and Marilyn had arrived at a new place in their relationship before her murder. Tragic—if he didn’t beat her head in.

“Everyone should be lucky enough to be loved for a long time. To know what that was like—to be loved and to change, to be privileged to suffer it, to remain. To know, as she did, that there was only one person she could ever love. To know it incontrovertibly. And accept it, with all of the attendant limits. Once you did, it was the closest thing there was to safety.”

Look, as a species, and often in relationships, I think we tend to be slow on the uptake. Shall we argue about it? We’ve been warned the world will warm destructively for decades and we have done…nothing about it. In Vertigo, Kim Novak meets Jimmy Stewart on the streets of San Francisco again, after she’s gotten away scot free, after she’s been an accomplice in the murder of Elster’s wife, a deception that leads to Stewart’s near-total mental collapse. And after she and Stewart meet again, he begins to violently transform her into the non-existent person he fell in love with—the most perverted retelling of Pygmalion there is, by the way. And what does she do the whole while? Protests meekly, but finally gives in. Does she tell him the truth? No, not till the very end of the movie when her life is threatened. Then she sees what she thinks is a ghost and falls, again—”We orbit, we repeat,” Detective Sheppard says—from the tower where she pretended to fall before. You get my drift and the allusion, I hope.

Chapter 16: Most people don’t murder their spouses—most, I’m guessing, wouldn’t even admit they’ve daydreamed about being set free by a convenient act of God—but a lot of people divorce, and in the process of divorcing they perform a kind of psychic murder—of each other’s best selves, of their own shared past. And the miserable couples who stay together but who don’t come to the realization Sam Sheppard comes to—those people kill each other, too, the “long double homicide” your Hitchcock scholar mentions. Could it be argued that the real question of this police procedural of the soul isn’t whether David Pepin killed his wife, Alice, but how he killed her?

Ross: Short answer: Yes. Some married people seem to spend their whole lives bleeding every ounce of bliss out of the other unto death.

“We tell stories of other people’s marriages. We are experts in their parables and parabolas. But can we tell the story of our own?”

But there are scarier things operating here, to me at least, and that’s how we can lose each other in marriage as well as ourselves. You’ve claimed you don’t recognize my book’s people, but as Hastroll says, “We tell stories of other people’s marriages. We are experts in their parables and parabolas. But can we tell the story of our own?” I’d ask you this: Ever come home from a dinner party with your husband and gone on and on about a couple you just couldn’t believe because they were so openly brutal to each other. You say to your husband: “Let’s not ever get like that, sweetie. OK?” “OK, dear,” he says. “Because,” you say, “if we ever got like that, darling, I’d just want to die.” “Don’t worry about it, honey. We won’t.” And you both hum happily home. But this is what I’m fascinated by in Mr. Peanut: the fact that the very couple you’re using as a caution may have once said that very same thing to each other one night driving home from a dinner party where they saw an unpalatable couple needle each other from cocktails through dessert. Like images you stare at in an Escher, they just didn’t realize they’d shifted into something else.

Chapter 16: Almost to a person, your characters are unmoored from any human connection apart from a sexual one. They have wives and lovers, but they don’t have parents or friends or neighbors or, most significantly in the context of the book itself, children. (I’m discounting Sam Sheppard because he doesn’t function in the novel as a member of any community until after his own epiphany, which comes too late.) How much of the inherent selfishness of this kind of relationship explains the misery in these marriages?

Ross: I disagree with that characterization. It’s the fact that the characters are unmoored from their spouses that leads them to suffer further disconnections literally or figuratively. In fact, I’d turn it around and argue that sex in the novel discloses how near or far these characters are from each other and from where they started as a couple. “Joy,” Sheppard thinks when he’s with his mistress, “This Sheppard reserved for his wife, no matter what was happening—or not—between them.” The distances these couples travel from each other forces them either to reject selfishness or embrace it because they feel all they have left in life is what they can get right now.

Chapter 16: There are a lot of Hitchcockian chickens in this story. Why?

Ross: Interestingly put. Do you mean characters who are chicken-shit, as in afraid? Or actual chickens? Hitchcock is a big part of David and Alice’s life together because they met in a Hitchcock seminar. Thematically, in films like Rear Window, Notorious, Strangers on a Train, and Vertigo, to name just a few, Hitchcock loved to explore both male anxiety with respect to powerful women as well as their idealization of same and how these forms of idealization can lead to terrible moral hazards. “She’s too perfect,” Jimmy Stewart says of Grace Kelly in Rear Window. Partly, he’s right, of course—I mean, she’s Grace Kelly—but he’s also confessing how threatened he feels by how accomplished she is, how much more powerful and capable she is than him—sexually and personally—and so he spends most of the movie projecting his desire for her death onto a jewelry salesman, Lars Thorwald, who lives across the courtyard from him, and may or may not have killed his wife. Very chicken-shit behavior, by the way, on both men’s parts.

Chapter 16: You’re probably sick of discussing the Escher-like structure of this novel’s interlocking marriages and reflective characters, so let me ask another question, trying to frame it in a way that won’t betray the truly astonishing revelation at the end: I think I can tell exactly where the staircase of this story is going up and where it’s going down. Can I? Did you design the question to be answerable at the end? Or did you intend for it to remain Escheresque—always both at once, depending on how you look at it?

Ross: The novel is Mobius strip. It has two discrete strands which are bound at the end. The question is: who binds them? On a formal level, the answer to that question is what I’m proudest of because it closes the loop with no exit, trapping the characters but not the reader.

Chapter 16: You’ve got an international book tour to conduct and a story collection to complete. After that, what’s next?

Ross: I have two projects pulling me in completely different directions. One is a novel about a New York boy whose father is a famous Broadway actor and the other is about a guy who dies and goes to Hell and learns the terrible duties of the damned. Both require beaucoup research. I can’t wait to get started.

To read a review of Mr. Peanut, click here.

(This interview originally appeared on June 22, 2010.)