Muse of a Different Sort

Beth Macy chronicles race, greed, and family in another true tale from Virginia

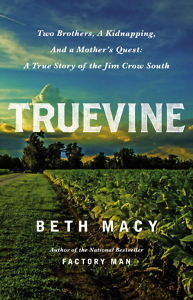

Truevine: Two Brothers, a Kidnapping, and a Mother’s Quest: A True Story of the Jim Crow South is an account of the kidnapping of albino African-American brothers George and Willie Muse of Truevine, Virginia, in the early 1900s. While helping their family sharecrop a tobacco farm, a bounty hunter tricked the two young boys away from their mother. Seeing their light skin and almost white dreadlocks, he sold them into the circus industry, and they became “Eko and Iko, the Ecuadorian Savages.”

Beth Macy’s first book, Factory Man, How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local—and Helped Save an American Town, sprang from her reporting with The Roanoke Times (and, full disclosure, focuses on members of my own extended family). This time she’s back with another true story from Virginia that’s hard to believe. Race, greed, and family figure into her latest tale, and her exhaustive interviews and research leave no stone unturned in this look at twentieth-century human trafficking. She recently answered questions about Truevine via email:

Beth Macy’s first book, Factory Man, How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local—and Helped Save an American Town, sprang from her reporting with The Roanoke Times (and, full disclosure, focuses on members of my own extended family). This time she’s back with another true story from Virginia that’s hard to believe. Race, greed, and family figure into her latest tale, and her exhaustive interviews and research leave no stone unturned in this look at twentieth-century human trafficking. She recently answered questions about Truevine via email:

Chapter 16: Your first book, the New York Times-bestselling Factory Man, is about the third-generation owner of a furniture factory in southwestern Virginia who fights the trend of outsourcing labor to Asia. The subject of your new book is vastly different—kidnapped African-American brothers. Other than their origins in Virginia, are the two stories related in any ways?

Macy: To me, they’re very much connected. Both cover a period of more than a hundred years, a time of vast cultural change. Both draw on an exploitive and racially charged climate, and both feature stories of gritty underdogs whose stories have largely been untold. Also, the driving time between Bassett and Truevine, Virginia, is all of about thirty-five minutes! As a side note, I had a Truevine native come up to me at a recent event for Factory Man to tell me that her father was an African-American worker who made ten cents an hour in a Bassett factory in the 1950s, and he supplemented it by being a lightning-quick moonshine runner. She was proud of the work he’d done on both counts!

Chapter 16: When your first book was released, you wrote a wonderful essay for the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard about your writing process for that book. The piece included photos of outlines taped to a wall, messy whiteboards, and timelines pinned to a cork board. Was your writing process similar for Truevine?

Macy: Yes, very much so. I try to always heed John McPhee’s advice on structure, and I always regret it when I get impatient and jump into a chapter without properly outlining it first. When I turned in the first draft of Factory Man, my editor, John Parsley, thought it sounded like two separate halves: the first being Bassett, the second being China. He suggested that I go back and put more of what was going on in China in the first half—to foreshadow, and to seep the reader into a more holistic range of the book.

I tried to build more of those techniques in as I was writing Truevine, and the timeline helped me do that. I love color-coding things (office-supply nerd alert!), and so every time I wrote something that I knew I wanted to come back to, or tucked in a hint, I put it in a color on the timeline, then made sure I looped back to that in a later chapter. It helped me track all those little hints and not-so-loose ends. There’s something about the act of moving around in my office, touching the timeline, getting up from my desk chair—things occur to me during those kinetic acts, little revelations that I find harder to access if it was all just pixels on a flat screen, buried somewhere deep in the bowels of my computer.

I’ll admit to being a bit of a Luddite—as the presidential debate was beginning, I had to phone both my son at college and my husband, who was away on a trip, to figure out the too-many remotes and the ridiculous button-mashing sequence required to turn on the damn TV. I think we all develop workarounds that click with our individual quirks, and my very tactile, moveable timeline really does work for me. Here’s a little video of how I use it. I should probably put some Wizard Wall up in my sunroom that outlines the seventeen steps required to turn on the TV.

Chapter 16: You write that A. J. Reeves, a blood relative of the Muse brothers, asked you during one interview, “Are you sure you want the truth?” In your research of the Muse brothers’ lives, did you uncover facets of institutionalized racism that surprised you, even considering the police brutality that is still happening today?

Macy: Oh, god yes. That the KKK was considered a respectable institution, led by prominent clergy members, favored politicians, and the city’s top prosecutor—that was a revelation, and so was the fact that newspapers routinely ran racist cartoons across the country; I quote from one, called “Hambone’s Meditations,” whose sole purpose was to make white readers laugh by mocking and humiliating black workers. I was stunned by the way the media covered the brothers’ story—frequently putting their stage names even in the headlines—but never once telling it from their point of view, never once acknowledging trafficking or peonage, only that “the fried chicken had given out in Roanoke,” as The New Yorker put it.

When I co-wrote the initial newspaper series in 2001, those archives weren’t as accessible. Now, it’s easier to see that the story was much more widely covered than we knew, and that in every single instance, in publications from The New York Times to The Roanoke Times, the brothers and their family were mocked at every turn. The micro-aggressions of daily living—like the racist parrots trained to squawk epithets at the black children on their way to school, or the N&W chef who could cook the executives’ food, using herbs from his home garden, but could not legally live on the same block—those were the trickled-down effects of that inculcated and institutionalized culture.

Chapter 16: In both of your books, you write in the style of new journalism—using first-person narration, recounting your researching and interviewing as they happen, and including yourself in the narrative. What are the benefits of this approach to writing nonfiction?

Chapter 16: In both of your books, you write in the style of new journalism—using first-person narration, recounting your researching and interviewing as they happen, and including yourself in the narrative. What are the benefits of this approach to writing nonfiction?

Macy: I’ve written essays and newspaper columns for many years, and in between I’ve written many more third-person articles and narratives. I’ve always felt in the latter that some of the best stuff got left out—those exchanges between the subject and writer that magazine writers get to write but that newspaper reporters are very strongly encouraged not to employ.

In Factory Man, it’s telling that John Bassett III called me numerous times a day, trying to direct the book—at one point leaving me an 8:00 a.m. voicemail after calling three times earlier that morning, saying,“I guess yo’ sleeping in today”—just as it’s telling that Nancy Saunders, the main character in Truevine, sometimes took eleven days to return my calls. John Bassett wants to boss me around. Nancy wants to prove that she doesn’t need me to tell her story, that she’s honoring me by letting me do it, not the other way around. Those are insights that a reader might not get through other anecdotes in the book. I don’t want to over-use it as a tool, but in general I find the technique a more honest and down-to-earth approach to telling a story. Also, by the time the books publish, there are few people quoted in them who have spent as much time with the main subjects as I have.

Chapter 16: Almost twenty years went into the making of your book, a time during which you won the trust of Muse descendants. Why is their story so important to you?

Macy: The story captivated me from the moment I first heard it nearly thirty years ago. It probably doesn’t hurt that it was initially suggested to me as a challenge: “It’s the best story in town, but nobody’s been able to get it.” I almost can’t remember a time in my career when I didn’t want to know more about this story. The same is true for most African-American Roanokers over the age of sixty who grew up hearing it as a cautionary tale, many of them thinking it wasn’t true. I wanted to get the story and tell it for the benefit of all of us, but mainly I wanted to bring full, belated honor to the badassery of Harriett Muse, an illiterate maid and everywoman who cleverly understood and subverted the racist systems she toiled under for decades and, ultimately, prevailed. In the end, just as Nancy predicted, her sons came out on top.

Chapter 16: Are there any parts to the story that didn’t make it into the book that you regret not being able to include?

Macy: I wish I had been able to convince Nancy to let me interview Uncle Willie before he died. (She said she didn’t believe I could sit on the story and not run it until after his death. “You’re too curious,” she said. She still calls me Snoop.) Everyone I spoke to who met him, from his nurses to the doctors and lawyers who knew him, described him as having an ethereal, almost godlike presence. I wish I could have seen him writing his name as an old man for the first time in his life, even though he was blind. I regret that I was not able to spend time at his bedside, to have witnessed him going from cautionary tale to wise elder. And the Snoop in me also would have had a few questions to ask about his earliest days on the road, I’ll admit!

Win Bassett’s work has appeared in publications including The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Oxford American, The Paris Review Daily, and Guernica. He serves as Editor-at-Large for The Sewanee Review and lives in Nashville.