Music From Many Roots

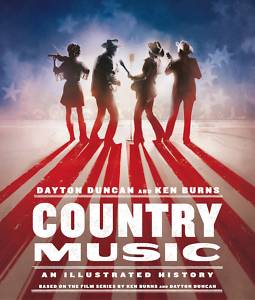

A companion book elegantly encapsulates the documentary series Country Music

Writer and producer Dayton Duncan has worked with documentary filmmaker Ken Burns for nearly 30 years. Their acclaimed explorations of American history and culture include The West, Lewis & Clark, and The National Parks: America’s Best Idea. Their most recent collaboration, Country Music, an eight-episode series for PBS, chronicles a musical genre that is often misunderstood or underrated, even by those who claim to love it. The companion book, Country Music: An Illustrated History, provides an elegant encapsulation of the material in the documentary, detailing country’s evolution and emergence as a musical form with broader reach and inclusion than many might think.

The book’s numerous colorful stories feature country’s well-known pioneers and innovators, but the narrative also covers key elements that are often overlooked, including the music’s strong African American influence. From the African origins of the banjo to the sizable impact of the blues, Duncan and Burns spotlight black contributions to the genre. They also detail the importance of religious songs and hymns, as well as Anglo-Celtic and mountain music. Country’s various branches, from Western swing and honky-tonk to bluegrass and rockabilly, also get rigorous investigation.

Through an array of stunning photographs, amusing-to-poignant reflections, and vital interviews, Country Music: An Illustrated History reveals the diverse sources of a beloved American music and takes a fascinating look at its place in the nation’s cultural fabric.

Dayton Duncan recently answered questions from Chapter 16 by email:

Chapter 16: What are the central themes that you hope readers will take away from Country Music?

Dayton Duncan: In our series, we approach country music as a uniquely American art form, and in telling its history several themes emerged.

What makes it uniquely American is that, like the nation and its people, it sprang from many roots. It’s never been one style of music, it’s always been a mixture: Anglo-Celtic ballads and fiddle tunes, African American blues and spirituals, church hymns and gospel songs, songs sung in fields and rail yards and on the border with Mexico and the open ranges of the West, in traveling minstrel shows and medicine shows. Its embrace is much broader than the common stereotype. In the course of the 20th century, from those diverse roots would spring many branches, again exploding the stereotype that country music could be confined into one simple category with clearly defined boundaries.

And, at its best, it is art of the highest caliber. It takes the most universal human emotions and experiences — love and loss, happiness and hardship, heartbreak and the hope of redemption — and distills them into songs, combining music and poetry into a delivery system that penetrates directly to your heart. The legendary songwriter Harlan Howard called it “three chords and the truth.” That means it’s often melodically simple, but the truth part — that’s much more complicated and profound.

It also sprang from the need of Americans of both races, who often felt left out and looked down upon, to tell their stories. Many of its greatest stars rose from backgrounds of almost inconceivable poverty and hardship, yet through their incredible artistry (and, perhaps, determination borne of those hardships) lifted themselves up — and [prompted] others to dream bigger dreams themselves.

That’s an American story, too.

Another theme is something I think separates country music from other genres: the special relationship between the stars and their fans. “When you look those people in the eye,” the singer Kathy Mattea told us, “they are you and you are them. There’s no being above.”

This is evident from the beginning. The Carter Family often stayed in fans’ homes when they were on the road; Jimmie Rodgers’ smiling, roguish spirit in the face of the tuberculosis that would kill him at a young age endeared him to people everywhere. And we trace that in every episode, all the way to 1996, when Garth Brooks, in the midst of his stratospheric rise that took country music to an entirely new level of popularity, showed up at a Fan Fair in Nashville and signed autographs for more than 20 hours!

Chapter 16: How does this book differ from seminal volumes on the subject, such as Country Music U.S. A. by Dr. Bill Malone or Nick Tosches’ Country?

Duncan: Bill Malone’s book, written 50 years ago, was the first, serious academic treatment of country music (at a time, he’ll tell you, when the thought of treating the music seriously was looked down upon). It was a “bible” for us in its comprehensive approach to chronicling country music’s origins and history. Tosches’ book, subtitled “The Twisted Roots of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” explores things from a specific point of view.

We’re old-fashioned narrative storytellers, trying to embrace a century of the music’s history (and how it interacted with the larger historical story of the nation), yet focusing on the biographies of the people who created that music. That means, on the one hand, we can’t be as encyclopedic as Bill Malone; for every story we tell in some detail, there are other people’s stories we simply don’t have room for. On the other hand, it means we have a wider frame of reference and a more ecumenical approach, perhaps, than Tosches.

There’s plenty of room for different approaches to covering a topic as broad as the history of country music. Ours is simply the way we’ve approached all of our explorations of American history, from the national parks to Lewis and Clark, from the West to the Dust Bowl, and so many others.

Chapter 16: Did you discover any surprises during your research?

Duncan: I try to begin each project with Ken by stripping myself of any preconceptions of what the story is and through the research allow it to tell me what the stories are that demand to be told. So even though I began the research more than eight years ago already somewhat familiar with the contours of country music, the process was one of continual surprises. I read hundreds of books, listened to thousands of songs, and interviewed hundreds of people (101 of them on camera) before starting to write. I consider that process one of the joys of what I do.

As a writer, I was particularly drawn to the stories behind the songs, hearing great songwriters explain what inspired them to create their masterpieces. Virtually all of those stories were surprises to me. I never knew, for instance, that Dolly Parton wrote “I Will Always Love You” as a way to persuade Porter Wagoner to let her go off on a solo career. My wife Dianne and I had always loved Kathy Mattea’s song “Where’ve You Been,” but I had no idea it came from the last words her husband Jon Vezner’s grandmother said to his grandfather. I was not prepared for the deep, emotional circumstances behind Vince Gill’s “Go Rest High on That Mountain.”

Those are just a few of the surprises. One that really hit me was learning that the Carter Family had been taught a gospel song, “When the World’s on Fire,” by Lesley Riddle, the African American who helped A.P. Carter collect songs. They recorded it, and then later used the same melody for their hit song “Little Darlin’, Pal of Mine.” Years later, Woody Guthrie — a fan of the Carters — used the same melody for his classic anthem “This Land Is Your Land.” In that one melody’s journey, the story of American music is encapsulated.

Chapter 16: Are there individuals who loom larger in your narrative about country music than they have in previous accounts?

Chapter 16: Are there individuals who loom larger in your narrative about country music than they have in previous accounts?

Duncan: We don’t set out on these projects to respond to previous accounts. As I said, we want the narrative to reveal itself to us. So in covering the roots and evolution of country music in the last century, obviously we cover the biographies of major figures others have included in their works: from Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family to Willie Nelson and Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton, and so many others. I’d like to think that our storytelling brings them to life and at the same time places them into a larger narrative.

I’m proud that we paid attention to the Maddox Brothers and Rose, whose Joad-like journey to California during the Depression ultimately ended up with them being known (and rightfully so) as “The Most Colorful Hillbilly Band in the World,” making music that was proto-rockabilly. I think the collection of what I considered the “Texas Bohemians in Nashville” — Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Rodney Crowell especially, who were as interested in creating great art as in commercial success — got more space than other histories of the music have usually provided.

Merle Haggard is clearly a major artist, but, except for those who knew him personally, I don’t think people understood how steeped in the music’s history — and how eloquently so — he was. He has something to say in every chapter, long before we get to his own remarkable career.

I think Emmylou Harris’s transformational position in the music’s evolution (and popularity) in the 1970s gets the recognition it deserves — from her time with Gram Parsons to bringing Rodney Crowell and Ricky Skaggs into her Hot Band; from inspiring Dwight Yoakam to go to Los Angeles and pursue a music that blended modern sounds with the oldest tradition to helping galvanize the effort to save and restore the Ryman Auditorium, the “Mother Church of Country Music.”

I’m not sure that Rosanne Cash has been understood as well as she should for her keen insights on country’s great songs or her own exquisite songwriting — versus as the daughter of Johnny Cash.

And I hope that readers who might not have known much about Marty Stuart will now recognize him as much more than a mandolin prodigy. He’s a living encyclopedia of the music’s history, a great American storyteller whose big, beating heart represents the best of what country has to offer the world.

Chapter 16: Traditionalists and purists have long criticized commercial country for being too close to rock and pop. What’s your take on this perennial complaint?

Duncan: One of the first things I realized is that there’s always been a tension between the traditionalists and those who want to stretch the boundaries of country music. Traditionalists didn’t like Bill Monroe reinterpreting Jimmie’s Rodgers’ “Muleskinner Blues.” Traditionalists also objected when Elvis showed up at the Opry and sang his reinterpretation of Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Some thought that Ricky Skaggs was committing sacrilege when he added electric guitars and drums to bluegrass. But that’s what artists do: They push boundaries, borrow from something old to make something new.

So contemporary complaints are nothing new. Neither are the cyclical responses that bring the music back closer to its roots.

Chapter 16: From your research, do you agree with the charge that women have gotten short shrift in country recently?

Duncan: We deal with history, not current events, which is why we end our narrative around 1996, about a generation ago. We need that arm’s length of time to make the hard choices we have to make, sifting through what may have seemed popular at the time from what turned out to be important, even if it wasn’t topping the charts.

But what the history of country shows so plainly is that it’s always had strong women at its core — and that it hasn’t always been easy for them; they’ve had to stand up for themselves and at the same time create their own “sisterhood” to move forward. The first great guitarist in country music, once it became recorded and broadcast, was Maybelle Carter. Patsy Cline was a force of nature with a remarkable voice (and she took young women artists newly arrived in Nashville under her wing, giving support and advice on how to navigate the country music world). Loretta Lynn was writing songs about alcoholism, spousal abuse, and a woman’s right to her own body and reproductive rights at a time when no other music genre had anything to say on those things. Both Dolly Parton and Reba McEntire are not only incredible talents, but huge successes in the businesses they run.

Those are just a few of the multitude of great women artists who populate the historical story we tell. I’m happy we’re telling it at a time when so many equally talented women artists are speaking out — and I think they will be heard.

Chapter 16: Where do you see country music going in the next 5-10 years? Who or what is influencing those trends?

Duncan: I believe that there is great music being made right now by many young artists, whether it’s heard on country radio or not. The new wrinkle is the expanding opportunities to reach audiences by means other than radio or by physical records and CDs.

As noted earlier, I deal in history, not the journalism of now or in predicting the future. If we make a sequel to Country Music 25 years from now, I’ll be better at answering that question.

Ron Wynn has appeared in documentary films on Muddy Waters and DeFord Bailey and written liner notes for many projects, including the Grammy-winning Night Train to Nashville, Vol. 1. He is currently the entertainment and sports editor of The Tennessee Tribune, the editor-in-chief of Everything Underground, a contributor to the Nashville Scene, and a columnist for the Tennessee Jazz & Blues Society website.