My One and Only Now and Forever

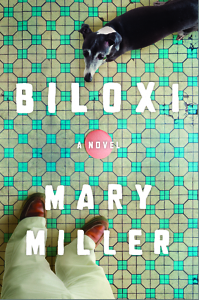

In Mary Miller’s Biloxi, a border collie leads a man in crisis out of ennui to enlightenment

Sixty-three-year-old Louis McDonald Jr. is at the end of his rope. Unemployed, alienated from his only child, and still smarting from the end of a thirty-seven-year marriage, the guy needs a friend. He finds one in the most simultaneously predictable and unlikely of sources: a dog.

In Biloxi, Mary Miller exhibits a deft and clever gift for drawing earnestness out of irony. The novel is at once a sincere and straightforward account of an irascible sad-sack reminiscent of Louis Begley’s Warren Schmidt and a gently ironic satire of the redemption-by-dog narrative so prevalent in popular culture. Through Louis McDonald’s voice, cranky but tinged with sadness and yearning, Miller evokes both the comic stories of Eudora Welty (the most revered writer to emerge from Miller’s native Jackson, Mississippi) and those of Joy Williams. She draws transcendence out of irony and the indignities of common human experience.

Like Welty and Williams, Miller has a knack for straightforward observations which, upon examination, resonate as profound truths, or, at the very least, as mysteries demanding contemplation. “She’s special,” Louis says of the dog, Layla, who is named after the legendary song Eric Clapton wrote about George Harrison’s then-wife. “As soon as I saw her I knew she was…. I stopped myself from saying ‘the one.’ There was no such thing as ‘the one,’ even when it pertained to a dog. I’d lived long enough to know that. The fact that I could love an overweight dog that gagged all the time and couldn’t catch a slice of bologna proved to me that there were other animals, and perhaps even people, out there that I could love.”

The theme carries over into the plot of Biloxi, albeit in a looser, less friendly manner. Louis acquires Layla from Harry Davidson, an archetypal shady Mississippian, whose wife, Sasha, has had about enough of him and hence does not need much persuading to migrate over to Louis’s house. Suffice it to say that Harry is less magnanimous than George Harrison about losing his wife, particularly to a guy who randomly showed up at his house for a dog.

Louis has other troubles: he’s still smarting from his divorce, he thinks (not incorrectly) that his daughter considers him pathetic, and he’s just quit his job on the expectation of an inheritance that seems increasingly likely to pass him by. “This was the tragedy of families, summed up in its entirety,” Miller writes. “You wanted to be known and loved for yourself and you also wanted to be someone who might be capable of living another life altogether.”

Louis has other troubles: he’s still smarting from his divorce, he thinks (not incorrectly) that his daughter considers him pathetic, and he’s just quit his job on the expectation of an inheritance that seems increasingly likely to pass him by. “This was the tragedy of families, summed up in its entirety,” Miller writes. “You wanted to be known and loved for yourself and you also wanted to be someone who might be capable of living another life altogether.”

Despite his ample shortcomings and grouchy disposition, Louis manages to move past being an object of comic curiosity. He endears himself through his curmudgeonly affection for poor gagging Layla, through his search for happiness and meaning, and through a rediscovery of the value of human connection, all facilitated by Mary Miller’s subtle gift for drawing the sublime out of the mundane.

“Everything going forward was up to me,” Louis says. “The story could change.” In Biloxi, Miller gets to the heart of what makes us all suckers for a good redemption-by-dog narrative: how caring for something that loves you back without condition or expectation revives both a sense of connection with the world and a sense of self-worth, how life inevitably seems to lead to unexpected places if you learn, as a dog always does, to follow your nose.

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in 2016. His second novel, So Wise So Young, is forthcoming from Algonquin in 2020. He lives in Nashville.