New Americana

Scott Gloden’s debut story collection delves into America’s identity dilemma

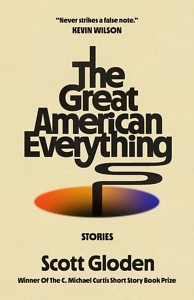

Scott Gloden was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, but “claims Memphis and New Orleans as homelands” according to Hub City Press, publisher of his debut story collection The Great American Everything. The collection received Hub City’s 2021 C. Michael Curtis Short Story Book Prize, given annually to an emerging writer from a Southern state. (Previous winners include Andrew Siegrist and Ashleigh Bryant Phillips.) Despite the expressly regional tag, Gloden’s stories could be called new Americana.

The title of the book is heavy with what linguists would call augmentatives: Great and Everything, words that convey intensity without much specificity. American seems no less a loud catchall term here. Perhaps, with the breadth of subject matter contained in this collection, Gloden is suggesting that Americanness is existential. The effect is like highlighting every sentence in a book, as if to say in an almost nihilistic tone that nothing has meaning. To be American, as Gloden’s stories demonstrate, is contradictory, humorous, achy, and any effort at definition is a valiant one.

The title of the book is heavy with what linguists would call augmentatives: Great and Everything, words that convey intensity without much specificity. American seems no less a loud catchall term here. Perhaps, with the breadth of subject matter contained in this collection, Gloden is suggesting that Americanness is existential. The effect is like highlighting every sentence in a book, as if to say in an almost nihilistic tone that nothing has meaning. To be American, as Gloden’s stories demonstrate, is contradictory, humorous, achy, and any effort at definition is a valiant one.

The titles of the stories deserve their own discussion. In several instances, they seem to add a layer of meaning which may not be readily apparent. The story “Tethys” is a prime example. The piece chronicles class and culture warfare in New Orleans by following the days of a sociology graduate employed at an art gallery. The pending sale of a particular painting brings about a fatal class confrontation. Readers will be hard-pressed to find the source of the title, however. Why “Tethys”? This word refers to many things — a type of gastropod, a moon of Saturn, a figure of Greek mythology. The student of literature might recognize Tethys as a poetic name for the sea. The title gives a wet quality to the story, conjuring up both the humidity of New Orleans, land erosion (the sea eating the city), and perhaps even the ways in which the protagonist cannot wash himself of his white middle class markers.

The collection is filled with a sort of white American awareness that seems to create its own genre. Whereas traditional Americana can tend toward a type of white innocence — think salt-of-the-earth, dustbowl, homesteaders, we the (innocent) people — Gloden ushers in a new Americana, where white folks from various landscapes in the South know not only that they are white but also the historical implications of being white, and thus live in a certain awareness. As the protagonist of “Tethys” reflects: “It was a decision to be a white person who moves to the white part of town, to go where others were quietly prolonging moneyed histories, to camp beside them and smolder, to iron an American flag into the lawn so they could watch me walk overtop it.”

But the awareness here moves beyond race. In Gloden’s “Birds of Basra,” the Nigerian American protagonist also tussles with issues of class: “Telly believes the worse part of town you live in, the better chance you have at being associated with the class you identify with. However, if our neighbors could see the eleven-dollar deodorants, the thousands of dollars of kitchen appliances, I sometimes think the association would fall apart.”

But the awareness here moves beyond race. In Gloden’s “Birds of Basra,” the Nigerian American protagonist also tussles with issues of class: “Telly believes the worse part of town you live in, the better chance you have at being associated with the class you identify with. However, if our neighbors could see the eleven-dollar deodorants, the thousands of dollars of kitchen appliances, I sometimes think the association would fall apart.”

Contemporary readers might recognize this crossroads between race and class as “intersectionality,” a term, coined in the 1980s by Dr. Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw that describes the ways compounding identity markers can both advantage and disadvantage the same individual. The protagonist is Black in the city and thus experiences racism, but quiet luxury items in her apartment portend an elevated class experience. This intersection between race and class is further complicated by the protagonist’s occupation as a caretaker, where she navigates her participation in an American system of elder abuse.

The closing piece, “Tennessee,” is a quixotic story about a mother on the downward descent toward dementia — quixotic because as the story nears its end, the reader might wonder if the joke of misremembering is on the protagonist’s mother or on us. The shift calls to mind Cervantes’ Don Quixote, who moves through the world under a shroud of lunacy. It is at the end of the story that we see beyond the shroud and realize Quixote has indeed been perceiving the same world as we have, only on a different frequency. In like manner, the protagonist of “Tennessee” must confront the question: What is reality anyway?

This timely collection of stories is linked by loss, love, and location — both social and physical. These 10 works are all set in the South but somehow offer a full sampling of the American identity dilemma. There is no one American culture. Gloden seems content to assert that perhaps to fall apart is not to be divided. It is instead simply to be and belong in this “everything” of states that we call America.

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian, who was recently awarded the Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is currently at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.