No Closure

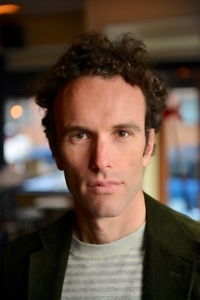

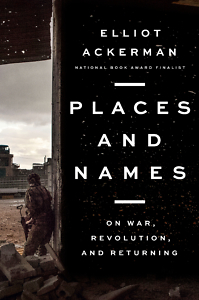

Elliot Ackerman’s memoir offers a soldier’s-eye view of conflicts in the Middle East

Nothing about the recent conflicts in the Middle East is simple. As Elliot Ackerman notes in Places and Names, his memoir about the region’s ongoing wars, alliances shift as circumstances change, and the distinction between friends and foes becomes muddled. The U.S. feels compelled to aid the Syrian rebels who are attempting to overthrow the brutal regime of Bashar al-Assad. But the rebels are joined by the Islamic State, a U.S. enemy for decades — though, in the 1980s, the U.S. actively supported their fight in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union.

Ackerman gamely endeavors to explain these complexities but acknowledges that even fighters on the ground have to maintain a fluid understanding of battle lines. He quotes the ancient wisdom that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in thought at the same time while still retaining the ability to function.” By that standard, the Syrian jihadists that Ackerman encounters are “some of the most intelligent people I’ve ever met.” Members of the defunct al-Qaeda and the Islamic State will never forgive the U.S. for its invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, but they would welcome its assistance in overthrowing Assad. “And why wouldn’t you arm the Islamists?” a former jihadist says to Ackerman. “You know firsthand what good fighters we are.”

Ackerman is well suited to interpret the intricacies of the Syrian morass. He joined the Marines in 2002 and served five deployments as an officer in Iraq and Afghanistan. After leaving the armed forces, he returned to the Middle East as a journalist, filing stories for Esquire and other outlets. He has also written three works of fiction, including Waiting for Eden (2018), each focused on lives sundered by the wars he witnessed up close.

Given the horrors Ackerman has seen, readers might wonder why he continually returns to the thick of the battle. Civilians assume that discharged soldiers would be eager to enjoy the safety of home, but soldiers miss the sense of purpose they felt in war. “If purpose is the drug that induces happiness, there are few stronger doses than the wartime experience,” Ackerman writes. He calls combat “the crystal meth of purpose,” whereas life in the States feels like drinking Coors Lite on the front porch, “watching life pass by.”

In addition to recalling his own wartime experiences, Ackerman provides a concise overview of Middle Eastern history, locating the origins of the region’s conflicts in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. After World War I, the Allies reneged on their promise to grant Arab tribes an independent state. Instead, England and France reached a secret compromise that divided Mesopotamia into colonial protectorates — present-day Iraq, Syria, and Jordan. That mendacious act, which ignored “the irregular borders of tribe, religion, and ethnicity,” initiated a century’s worth of internecine struggle.

In addition to recalling his own wartime experiences, Ackerman provides a concise overview of Middle Eastern history, locating the origins of the region’s conflicts in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. After World War I, the Allies reneged on their promise to grant Arab tribes an independent state. Instead, England and France reached a secret compromise that divided Mesopotamia into colonial protectorates — present-day Iraq, Syria, and Jordan. That mendacious act, which ignored “the irregular borders of tribe, religion, and ethnicity,” initiated a century’s worth of internecine struggle.

In 2014, the leader of the Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, at that time making inroads into Iraq, called for the establishment of a caliphate that would extend from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. They announced a plan to take by force what was stolen by subterfuge. “This blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy,” al-Baghdadi declared.

The Muslims Ackerman interviewed confirm that this vision of a pan-Arab state is widely held. In the most tense chapters of Places and Names, Ackerman meets with Abu Hassar, a former al-Qaeda jihadist who fought against U.S. troops in Iraq. As Abu Hassar points out, Islamists and the U.S. share the goal of deposing Assad in Syria, but ultimately they will be on opposing sides. He envisions that “the armies of the West will fight the Islamic armies of the East in a great end-of-days battle … And God will make his judgment.”

The U.S. soldiers that Ackerman encountered don’t bother speculating about endgame scenarios. Instead, they imagine that they are starring in their own movies. Ackerman recalls that during his time in Iraq, “[M]any Marines I knew, guys in their late teens or early twenties, would behave as they thought Marines at war are supposed to behave,” roles gleaned from Vietnam films, such as Full Metal Jacket and Platoon. “But our war was real. Or was it?” Ackerman writes. “We were imitating a story.”

All the role-playing and political posturing doesn’t change the reality that lives are being lost. Ackerman’s memoir recounts the names of friends who died in battle and asks the most difficult question, “Was it all a waste?” He knows that there is no easy answer. Places and Names offers a startling portrait of the open-ended struggle, refuting the notion that a permanent peace is on the horizon. “Returning to the country where I fought my war, while that country is still at war, offers no closure,” Ackerman writes. “My war is not over.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.