Of All Places

A Nashville journalist maps a Syrian-American restaurateur’s moving journey to Hendersonville

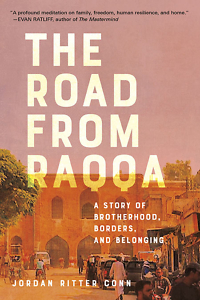

The Road from Raqqa is no doubt the only book, ever, that features the Assad regime, Country Music Hall of Famer Ricky Skaggs, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Food Network’s Guy Fieri. The real-life characters depicted by author Jordan Ritter Conn are, it turns out, as discordant as the values and the people that earnest young Syrian immigrant Riyad Alkasem finds when he arrives in the United States.

In Syria, Riyad Alkasem was a brilliant student whose legal knowledge and prowess were so advanced that he was on track to become a judge in his 20s. But when he landed in Los Angeles in 1990, full of idealism and a plan to learn English and study law so that he could amass enough education to return home and help free his people from a murderous regime, the only job he could find was as a dishwasher in an Italian deli, where he eventually replaced the cook.

In fact, when it was clear Riyad was leaving Syria, his grandfather counseled him, “Cook them food.” But throughout his childhood, all Riyad wanted to do was to get away from the government that ruled Syria. “Riyad became one of the most dangerous kinds of people in all of Syria: a loud-mouthed kid with a hatred of the regime,” Conn writes. “As he grew older, he heard more whispers, more news of the regime’s abuses of power. Assad’s spies monitored his own people more closely than they did foreign enemies. … Protests had been banned since 1963.”

Once in America, education took a back seat while Riyad earned enough money simply to survive and send some back home to his family. He was met with generosity from his landlord, and employers recognized his hard work and treated him kindly.

While the $250 a week he was earning in those early days would put him squarely in the professional class back home, it was barely enough to cover his living expenses, including rent for a single room in a boarding house. But, as ever in America, industriousness paid off and eventually earned Riyad a business partnership with a Syrian Christian running a liquor store in Santa Barbara. (Never mind that he is a devout Muslim who prays five times a day, doesn’t eat pork, and swears off alcohol.)

He fell in love, married, had kids, bought a house. And then came September 11, 2001.

At the time, his brother Bashar was in the U.S. too, having come to visit their father, who fell ill on a visit and was hospitalized in California. Though he had a work permit and a job, a bureaucratic snafu rendered Bashar’s visa invalid for two weeks during his stay. Post-terror attack, the federal government required non-citizen immigrants from 24 Muslim countries to report to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. When Bashar did, it was the beginning of the end to his time in America. Though his paperwork was in order, the agents spotted the prior two-week visa violation. They detained him and jailed him for three days.

“The officials seemed to delight in his pain and confusion,” Conn writes. “He would remember being called a ‘terrorist’ and a ‘raghead,’ asking for food and being given a sandwich, and then the guards laughing when he realized that it was bologna, which was pork, which was for Muslims forbidden, haram.”

“The officials seemed to delight in his pain and confusion,” Conn writes. “He would remember being called a ‘terrorist’ and a ‘raghead,’ asking for food and being given a sandwich, and then the guards laughing when he realized that it was bologna, which was pork, which was for Muslims forbidden, haram.”

Bashar was set for deportation but left on his own before it could happen, his American dream having been more of a nightmare he was ready to leave behind. A year later, their father died, and Riyad moved to his wife’s hometown of Hendersonville, where he and his family had to start all over. His business partnership had ended in acrimony, and his middle-class life right along with it.

Hendersonville was 85 percent white and almost as red. “In 2004, soon after George W. Bush launched a war that killed untold numbers of Muslims in Iraq, 65 percent of Sumner County’s residents had voted to reelect him,” Conn writes. “It was the place where Riyad had been called a ‘sand nigger,’ where he’d been rejected for countless low-wage jobs and denied applications for low-rent homes.” One EEOC employee even told a frustrated Riyad, who had gone in to file a complaint, “Oh honey, you’re gonna have to move.”

But he didn’t. Hendersonville was home now. And that’s where he decided to start Café Rakka — because Café Raqqa with a Q seemed a bridge too far.

At that time, Bashar could never have imagined the 2011 Arab Spring that was coming and what was in store for his mother and his new young family. Conn’s recounting of their separate journeys, and their desire always to make their way back to one another, is deft and moving. Across miles and even ideology, the brothers never waver in their love for each other and their commitment to family.

Conn, a staff writer for The Ringer who worked for ESPN at the time, met Riyad in 2016 when he was looking for an Arabic translator for a story he was working on about a soccer team aligned with the Syrian rebel forces. He was steered toward Riyad at Café Rakka. Over shawarma and baba ghanoush, Conn began to learn about Riyad’s life.

The Road from Raqqa isn’t just a memorable and well-told immigrant’s story or the gripping account of a family’s life torn apart by war. It’s also an examination of what it means to be an American in all of its complicated and sometimes inglorious ways. And about learning to let go of a dream, realizing a new one has taken its place.

Liz Garrigan is the former editor of the Nashville Scene and Washington City Paper. She lives in Bangkok, Thailand.