Of Blood and Darkness

Cormac McCarthy returns with The Passenger and Stella Maris

Sixteen years have passed since Cormac McCarthy published The Road, which won a Pulitzer, became an international bestseller, and further cemented his reputation as one of the major writers of his generation. Given that he was 73 then, the question of whether he would ever publish another novel has long been the subject of rumor and online gossip. The chatter intensified with the announcement in 2015 that McCarthy was purportedly nearing completion of not one but two new companion novels.

Now, The Passenger and Stella Maris are here, in quick succession. The just-released Passenger will be followed by Stella Maris (along with a box set of both novels) on December 6. They are separate, stand-alone volumes that nevertheless complement each other in a more intimate manner than the three installments of McCarthy’s so-called Border Trilogy. Set primarily in the South (along the Gulf Coast and in East Tennessee, where McCarthy grew up, but also at a psychiatric hospital in Wisconsin), the new novels represent both a homecoming of sorts and a departure. Their protagonists are mathematics prodigies obsessed with theoretical physics and epistemology. McCarthy’s last frontier, it seems, is not the West, but ontology: that is, the study of the nature of being.

That said, The Passenger opens in the shape of a suspense novel. Bobby Western, a salvage diver, is hired to search the wreckage of an airplane sunk off the Gulf Coast near the border of Louisiana and Mississippi. Western and his colleagues discover that the plane’s black box has disappeared, along with one of the passengers listed on the flight manifest. Shortly thereafter, dubious federal authorities visit Western, initiating a cat-and-mouse game. In addition to his reluctant involvement in the mystery of the missing passenger, Western also has a complicated personal history involving advanced mathematics, Formula One racing, a literal buried treasure of gold coins, a priceless violin, and the Manhattan Project. To make matters even more complex, Western is grieving the death of his sister, with whom he was deeply in love.

That said, The Passenger opens in the shape of a suspense novel. Bobby Western, a salvage diver, is hired to search the wreckage of an airplane sunk off the Gulf Coast near the border of Louisiana and Mississippi. Western and his colleagues discover that the plane’s black box has disappeared, along with one of the passengers listed on the flight manifest. Shortly thereafter, dubious federal authorities visit Western, initiating a cat-and-mouse game. In addition to his reluctant involvement in the mystery of the missing passenger, Western also has a complicated personal history involving advanced mathematics, Formula One racing, a literal buried treasure of gold coins, a priceless violin, and the Manhattan Project. To make matters even more complex, Western is grieving the death of his sister, with whom he was deeply in love.

Despite these dramatic trappings, The Passenger is far less a thriller than a pessimistic but beautifully rendered meditation on humanity’s relationship to nature. For reasons that become clearer in The Passenger’s sequel, Stella Maris, McCarthy alternates chapters narrating Bobby Western’s journey with italicized scenes featuring Western’s beloved late sister Alicia, a paranoid schizophrenic, and a slew of grotesques who populate her hallucinations. As in many of his novels, the dense, extended conversations between characters serve as a means for McCarthy to distill his philosophy in the alternately terse and neo-biblical style for which he is famous.

The second installment, Stella Maris, completes the story of Alicia Western through her sessions with a psychiatrist at the eponymous hospital where Alicia has voluntarily committed herself. The Passenger has already revealed that Alicia is a math prodigy and most likely a genius; in Stella Maris, her vivid ruminations may offer a key to the method at work in some of the more mysterious aspects of McCarthy’s fiction, dating back as far as his bizarre Gothic novel Outer Dark (1968), which, coincidentally, is the only other one of his books with a female protagonist.

The second installment, Stella Maris, completes the story of Alicia Western through her sessions with a psychiatrist at the eponymous hospital where Alicia has voluntarily committed herself. The Passenger has already revealed that Alicia is a math prodigy and most likely a genius; in Stella Maris, her vivid ruminations may offer a key to the method at work in some of the more mysterious aspects of McCarthy’s fiction, dating back as far as his bizarre Gothic novel Outer Dark (1968), which, coincidentally, is the only other one of his books with a female protagonist.

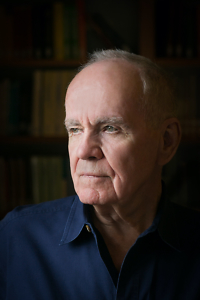

The jacket copy for The Passenger describes McCarthy as “our greatest living writer.” It is probably more useful to think of him as the last great exemplar of a particular kind of writer. Even for his own cohort, he is a throwback — an unapologetic modernist, echoing Hemingway with his terse narration and rugged, taciturn men, and Faulkner with his deviations into stream-of-consciousness description and striking metaphors. His primary themes are archetypal: the senseless brutality of the human race and the stoic protagonist’s futile struggle to persist in the face of said brutality.

In both The Passenger and Stella Maris, in keeping with the modernist credo, he fixates on the paradoxical nature of technology — namely, how miraculous scientific discoveries inevitably end up being tools of horrific destruction. We learn early in The Passenger that Bobby and Alicia Western are the children of a fictional nuclear physicist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory who helped design and manufacture the first atomic bombs. They are both bound and haunted — perhaps cursed — by the consequences of this fact. (Alicia may even be indirectly responsible for a breakthrough that made the bombs possible.) McCarthy, perhaps the most lyrical poet of slaughter since Homer, is at his most biblical and elegiac describing the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: “In that mycoidal phantom blooming in the dawn like an evil lotus and in the melting of solids not heretofore known to do so stood a truth that would silence poetry a thousand years.”

The truth to which McCarthy refers here will likely be debated some time to come. What seems beyond dispute is that The Passenger and Stella Maris together form a profound addition to the legacy of a true literary savant.

Ed Tarkington is the author of two novels, The Fortunate Ones (2021) and Only Love Can Break Your Heart (2016). He lives in Nashville.