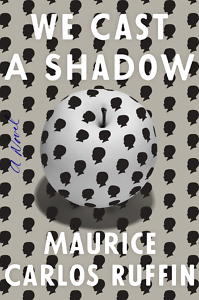

At the end of January, Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel bounded out of the gate with auspicious momentum. We Cast a Shadow has already garnered glowing coverage from a wide range of outlets, including the Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, The Paris Review, NPR, Literary Hub, and news sources covering Ruffin’s hometown, New Orleans.

We Cast a Shadow conjures a powerful spell. Driven by fierce, possibly blinding love for his son, the novel’s unnamed protagonist makes decisions that expose his family to a dangerous landscape that may seem dystopian but in fact lies excruciatingly close to our own. As the novel’s world grows increasingly off-kilter in its surface reality, its emotional resonance deepens and darkens.

Ruffin answered questions for Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: So many of this book’s details evoke the places and traditions of New Orleans. What led you to decide not to name the setting?

Maurice Carlos Ruffin: In books like The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead and Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, the authors never specify time or place. It lends a fable-like quality, even though the setting felt real. I like the fact that fables allow us to believe anything might happen, and I like having that flexibility in the book.

Chapter 16: The novel opens with a humiliating costume competition that pins the narrator’s future in a tony law firm on the all-white partners’ scrutiny of his costume. Masks and other concealments (including the fact that the narrator remains unnamed) recur throughout the book. How would you describe your relationship to costume?

Ruffin: At one point the narrator, who is a lawyer like myself, talks about how his business suit is like a suit of armor. I agree. There’s a vast difference in the way I’m treated while wearing a suit versus wearing jeans and a hoodie. Even though I’m still the same person, I’ve literally never been harassed by an officer or store owner while wearing a suit. Also, New Orleans is a tourist city, so many of us put on actual costumes, as well as a chipper demeanor, to make a living.

Chapter 16: In numerous reviews and other press, your novel has been discussed through the lens of satire. Is this a fair orientation toward the book?

Ruffin: I’ve seen a definition that says satire is about being petty towards something you don’t like. I don’t like racism, so I think that’s probably a fair description of the book. During his adventures, the narrator sets off many racist traps, and his actions allow us to see how ridiculous racism can be. It’s the same tradition that Voltaire, Jonathan Swift, John Kennedy Toole, and Ralph Ellison worked in.

Chapter 16: The aspects of the novel’s world that depart from our own timeline emerge subtly and only begin to ramp up once we’re deep inside the narrator’s life and dilemma. How did you approach weaving in those speculative elements?

Chapter 16: The aspects of the novel’s world that depart from our own timeline emerge subtly and only begin to ramp up once we’re deep inside the narrator’s life and dilemma. How did you approach weaving in those speculative elements?

Ruffin: I wanted readers to take the ride with the narrator. He’s not shocked at the details that separate his world from ours because he is used to them, so the reader shouldn’t be shocked. I prefer the reader to fall into the dream of my novel. I want them to wake up near the end and wonder how they traveled so far without noticing.

Chapter 16: Alexander Chee describes the relationship between a writer and a novel-in-progress as “the heart’s ruse.” What was living with this novel like during its germination?

Ruffin: The novel was like a very noisy baby. It hogged my attention, interrupted my sleep, and made me miss many social events. But I wouldn’t have had it any other way. Like raising a child, the novel helped me shift perspectives and mature. I see the world differently because I wrote this book. I think I have a much clearer view of our country and our history than I did before. My heart wanted me to know more than I did. The novel ensured that I gained this knowledge.

Chapter 16: Last fall, you were featured in a dazzling photo shoot by the New York Times Style Magazine called “Black Male Writers for Our Time,” which gathered thirty-two extraordinary writers spanning many generations and genres. Ishmael Reed, James McBride, Danez Smith—the list goes on. What was it like to be in that room?

Ruffin: It was like being invited to the adults’ table at Thanksgiving. Those writers represent so much of America’s talent, intelligence, and brilliance. I took part in many conversations, but, mostly, I listened. I could have lived in that afternoon for months.

Chapter 16: You’ve written prolifically about New Orleans, in both fiction and nonfiction. How has writing about New Orleans changed your understanding of your hometown?

Ruffin: I think that writing about my hometown made me research stats, dates, and historical events in a way that opened my eyes time and time again. I’ve lived here my whole life, but I’m not sure I understood anything about the place until the past five years or so. The writing also helped me explore my own assumptions and figure out what I think about how I feel.

[This article originally appeared on February 25, 2019.]

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction has been published in Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.

Tagged: 2019 Southern Festival of Books, Fiction, Q&A