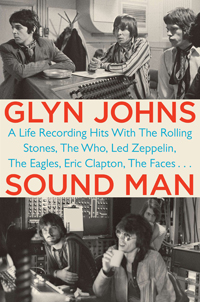

On the Record

In Sound Man, Glyn Johns recalls his many encounters with rock’n’roll royalty

In the opening pages of his memoir, Sound Man, record producer Glyn Johns offers his answer to the question of what exactly a record producer does: “You just have to have an opinion and the ego to express it more convincingly than anyone else,” Johns writes. “Every time I start another project, I wonder if I am going to get found out.”

That self-deprecating wit is a hallmark of his reflections on more than five decades in the music business. More of a collection of anecdotes than a true autobiography, Sound Man devotes little space to Johns’s personal life, instead focusing on vivid memories of a lifetime spent in the studio with a who’s who of classic-rock artists, including the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Who, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, the Eagles, the Clash, and more.

That self-deprecating wit is a hallmark of his reflections on more than five decades in the music business. More of a collection of anecdotes than a true autobiography, Sound Man devotes little space to Johns’s personal life, instead focusing on vivid memories of a lifetime spent in the studio with a who’s who of classic-rock artists, including the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Who, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, the Eagles, the Clash, and more.

The book includes a brief outline of Johns’s youth as a jazz- and rock’n’roll-obsessed boy growing up in the suburbs of London. In 1959, at seventeen, Johns secured a job at IBC Recording Studios in London through pure happenstance. At first he saw the position purely as a way to learn about the music business in hopes of furthering his singing career. As he mastered the ins and outs of sound recording, it gradually became apparent his true talent lay not in front of a microphone but behind a recording console—a realization that became fully apparent after he secured his own recording contract in 1965 and left his job at IBC.

“The reviews were quite encouraging,” Johns writes. “I did the usual promotion, a couple of TV shows and a handful of interviews in the music press. All to no avail. The record did not sell and within five or six weeks I was back at home twiddling my thumbs, realizing, among other things, that in order to be a successful singer you had to be able to remember the lyrics to a song. Something I had serious trouble with.”

Some of the most engaging parts of Sound Man are Johns’s accounts of both the London rock’n’roll scene in the pre-British Invasion years of the early sixties and his close friendships with many rock’n’roll and blues-obsessed musicians. By 1962, he was scouting new talent for IBC and producing demo recordings. The first group Johns brought into the studio was the Rolling Stones. Although his first recordings of the band did not lead to a record contract, the friendship they developed at the time led to his working with the Stones as a recording engineer for the next thirteen years.

Some of the most engaging parts of Sound Man are Johns’s accounts of both the London rock’n’roll scene in the pre-British Invasion years of the early sixties and his close friendships with many rock’n’roll and blues-obsessed musicians. By 1962, he was scouting new talent for IBC and producing demo recordings. The first group Johns brought into the studio was the Rolling Stones. Although his first recordings of the band did not lead to a record contract, the friendship they developed at the time led to his working with the Stones as a recording engineer for the next thirteen years.

During the 1960s, as changes swept over pop music, Johns was in a prime position as one of the top recording engineers who understood the “new sound” of rock’n’roll music in the “mod” decade. Through the 1970s and into the twenty-first century, he worked as a successful freelance producer, engineer, and sound mixer, having a hand in many now-classic recordings. Sound Man recounts these experiences through a string of entertaining stories, relating Johns’s personal and business interactions with a long line of British and American rock’n’roll royalty. The book also details lesser-known projects that have remained his personal favorites, including the multi-artist historical concept albums, White Mansions (1978) and The Legend of Jesse James (1980).

In writing about conflicts and problems with artists—the effects of drugs on talents like the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones and legendary British guitarist Eric Clapton, for example, or the personal animosities between the Beatles during the troubled sessions for the Let it Be album and documentary—Johns doesn’t traffic in gossip or sensationalism. He discusses such matters purely in terms of how they related to the work he was doing and the records that were being made.

Although he doesn’t completely avoid criticism of others, he clearly has no axes to grind. In writing about creative differences or personal conflicts, he employs an even-handed tone that illustrates his ability to serve as an island of stability and professionalism in a sea of wild creativity, out-of-control egos, and self-destructive lifestyles. Johns also doesn’t shy away from expressing his own opinions and tastes, arguing that producer Phil Spector “puked all over” Let it Be (a viewpoint many Beatles fans share) and offering his low view of the Eagles’ later recordings, as well as his general disdain for punk rock. But even in these instances he is merely living up to his personal definition of a record producer: having a firm opinion and the ego to express it.

As a rock-history text, Sound Man mostly covers familiar territory, but it delivers an engaging and immensely enjoyable chronicle of the life of a person who was repeatedly at ground zero of many classic moments of rock’n’roll history.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.