One-Term Wonder

Journalist Robert W. Merry considers the expansionist presidency of James K. Polk

James K. Polk, the one-term president from Columbia, Tennessee, oversaw one of history’s greatest and, in relative terms, least bloody land grabs. Between 1845 and 1849, he led the United States in acquiring Texas, the Oregon territory, California, and a large swath of northern Mexico—what today comprises Nevada, Utah, and parts of New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. Only the last involved bloodshed, the result of the Mexican-American War. When Polk took the Oath of Office, the United States was an Atlantic power beset by the British to the north and Spanish and French interests to the south; by the time he left, the country had secured its dominance over North America and set in motion the economic boom that would drive it to global preeminence in the next century.

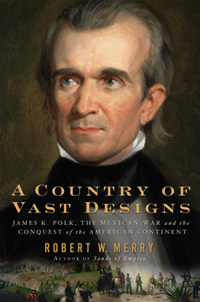

Yet for all the importance of the Polk Administration, the man himself presents historians with a problem: How do you write a compelling narrative about one of America’s all-time boring politicians? This isn’t a flip question. Polk was a dour introvert at a time when the American stage was dominated by larger-than-life characters, from the aging Andrew Jackson, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay to the young Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. Polk was neither a compelling speaker, like Clay or Lincoln, nor a dashing war hero, like Jackson or Grant. He traveled infrequently, attended only the obligatory social functions, and rarely related his thoughts to confidants, nor even to his journal. “He struck many as a smaller-than-life figure with larger-than-life ambitions,” writes journalist Robert W. Merry in his new book, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent.

The result is a man whom we can see only in outline, though we feel compelled to fill in the blank spots by the significance of the historical moment. “Probably no other president presents such a chasm between actual accomplishment and popular recognition,” Merry concludes.

The result is a man whom we can see only in outline, though we feel compelled to fill in the blank spots by the significance of the historical moment. “Probably no other president presents such a chasm between actual accomplishment and popular recognition,” Merry concludes.

Some biographers, particularly the earlier ones, drew Polk as a hard-working idealist, who saw westward expansion as a heavenly mandated right bestowed on the United States. Others, more critical, showed Polk as a Southern partisan whose westward urges were underlined by a drive for more slave territory to check the industrial and political power of the North. Merry, however, takes a third tack, portraying Polk as a sort of proto-Nixon, a hard-bitten realist who transcends sectionalism and party politics in the quest for continental dominance.

Merry is not alone—Polk’s willingness to flaunt international rules of engagement and the moral sentiments of the founding fathers regarding unnecessary wars have led many historians to paint him as the first great American imperialist. Merry, however, wants to temper that image. For him, Polk may have been a Machiavelli, but he was no criminal. “Polk wanted war … but he didn’t want to start it,” Merry writes. Instead, he simply played a game of brinksmanship with Mexico—annexing Texas, sending in an offensively armed occupying army—in the hope that his country’s southern neighbor would fire the first shot. When it did, Polk quickly took advantage and crushed it.

Merry’s Polk may be colorless, but he’s also a savvy, efficient operator. He may not be a great public speaker, but he can flawlessly read the winds of national sentiment. He may not have ideals, but he can tack his way expertly through political storms. As Merry shows in intricate detail, Polk operated within a tangled web of sectional and party crosscurrents, pitting not only Whigs against Democrats, but Southern against Northern Democrats, expansionists versus doves, and pro-government pols against economic populists. On top of all that came machinations about the 1848 election, in gear early because Polk had taken office promising to be a one-term president.

Merry’s narrative is not for everyone; those looking for tense war stories had best look elsewhere. Most of the book centers on 1840s Washington intrigue, a field at once recognizable today—hyper-partisan media, Cabinet leaks—and completely foreign to modern sensibilities, most notably in the glacial pace of news from Mexico, which could take weeks to reach the White House.

And yet Merry does an excellent job with the material at hand. Not only is his explanation of the political currents clear, but he manages to relate a level of historical nuance not often found in general-interest writing. Merry captures the political tectonics perfectly, highlighting the irony that Polk, as a Democrat, was using the government to expand the nation’s territorial reach, while opposed by usually pro-government Whigs afraid that growth to the southwest would empower the slave-owning states. Polk’s zeal put him at odds with the party elders, notably Calhoun, and in an odd-couple friendship with the Whig Henry Clay, the mortal enemy of his mentor Andrew Jackson.

And that’s just the politicians. Polk also found himself in the middle of a growing abolitionist movement and rising separatist sentiments in the South, united by a fiery national push for westward expansion, if rarely for the same reasons. But where others saw disagreement, Polk saw opportunity. Americans wanted expansion, Merry writes, and “in the end he succeeded and fulfilled the vision and dream of his constituency. In a democratic system that is the ultimate measure of success.”

And that’s just the politicians. Polk also found himself in the middle of a growing abolitionist movement and rising separatist sentiments in the South, united by a fiery national push for westward expansion, if rarely for the same reasons. But where others saw disagreement, Polk saw opportunity. Americans wanted expansion, Merry writes, and “in the end he succeeded and fulfilled the vision and dream of his constituency. In a democratic system that is the ultimate measure of success.”

Fair enough. But despite the thoroughness of Merry’s narrative, the reader is left wanting something more. Simply doing what the people want can never be the primary criterion for assessing a presidency since, especially in a history of the 1840s, assessing the true national impulse is a shaky proposition. And in any case, even within that criterion, there are good and bad ways to do it. How should we assess Polk within the context of the approaching Civil War? Did his bellicosity and expansion-at-all-costs mentality make secession more or less likely? What did Polk ultimately think about slavery, the most pressing question of the day? Merry provides some of the evidence for drawing our own assessments, but he himself is silent.

Perhaps the most striking thing in Merry’s book, though, is not found in the words but the pictures. The first image in the photo insert, a painting of Polk at the outset of his presidency, shows a hale and hearty man in his late 40s. The last is a photograph showing Polk just four years later; his face is sunken, his eyes are tired, and his hairline much is receded. He died just a few months after leaving office, having literally worked himself to death. If nothing else, Merry’s book is a clever profile of an ordinary man with extraordinary vision, a man who realizes his dream but loses his life in its pursuit.