Opening a Window on the Universe

Jess Walter on the audacity and terror of writing novels

Jess Walter’s The Cold Millions takes readers back to the turn of the 20th century in Spokane, Washington. There we meet Gregory (Gig) and Ryan (Rye) Dolan, brothers who have been riding the rails and have landed in Spokane: Gig’s favorite city, “the theater capital of the west,” and the latest place where the radical labor union Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is protesting unfair employment practices. Gig, a faithful member and burgeoning union agitator, is there to join the action. Sixteen-year-old Rye is there because after their mother died, all he could think to do was find Gig.

Before they know it, one police officer is dead and another assaulted, the union protest turns violent, and Gig is thrown in jail with hundreds of other activists. The rest of the story unfolds, introducing brilliant characters such as the fictional burlesque performer Ursula the Great and the very real (and very young) Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an idealistic firebrand in the socialist labor movement. Readers will be swept up by the action, immersed in the historical time and place, all the while grappling with such issues as income inequality, justice, and our shared human dignity — as relevant today as they were over 100 years ago.

Before they know it, one police officer is dead and another assaulted, the union protest turns violent, and Gig is thrown in jail with hundreds of other activists. The rest of the story unfolds, introducing brilliant characters such as the fictional burlesque performer Ursula the Great and the very real (and very young) Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an idealistic firebrand in the socialist labor movement. Readers will be swept up by the action, immersed in the historical time and place, all the while grappling with such issues as income inequality, justice, and our shared human dignity — as relevant today as they were over 100 years ago.

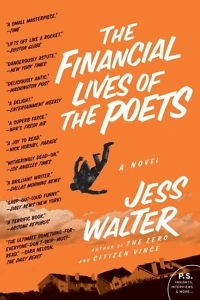

Published in October 2020, The Cold Millions was praised widely, landing on numerous Best of the Year lists. It joins Walter’s bestselling The Financial Lives of the Poets, Beautiful Ruins, and National Book Award finalist and stunning 9/11 novel The Zero, among others.

Walter spoke with Chapter 16 by phone ahead of his session with the 2021 Southern Festival of Books, held in person at Parnassus Books in Nashville on October 4. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: I’m really excited to have a chance to talk about The Cold Millions. Let’s start with that title. The passage where it originates reads, “All people, except this rich cream, living and scraping and fighting and dying, and for what, nothing, the cold millions with no chance in this world.” I wonder if you could unpack that moment and how you came to decide on the title.

Jess Walter: This comes as Rye’s in the library of this wealthy man [Lem Brand, owner of the mining operations in town], and he’s heartbroken by the fact that his brother Gig will never see such a place. Every once in a while, there’s a bit of writing that’s like the ring of a tree, that you can look at and remember the process of writing the book itself. For a while, I thought this was going to be even more of a Western than it is, and I had this title on it, Nothing West of Dead, which is another line in the book.

But as I typed that phrase, “the cold millions,” I got a chill and thought, That’s the book I’m writing. Whatever Nothing West of Dead is, it sounds like a great book, but that doesn’t happen to be the book I’m writing. As entertaining and rip roaring and wild as the characters were, it was really this idea of how we take care of the least of us that animated and drove the book.

Chapter 16: That makes me think of another passage, early on when Rye is reflecting on the idea of equality:

Hell, it took only your first day in a Montana flop or standing over your mother’s unmarked grave to know that equal was the one thing all men were not. A few lived like kings, and the rest hugged the dirt until it cracked open and took them home.

Walter: Drawing that connection between the sense of adventure those two brothers have and the unfairness of income inequality — circa 1909, circa now — is what I really wanted to write about. I wanted that anguished cry for fairness to come out of Rye, but I also wanted him to have some sense of control in his own life. I wanted the book to have those two tones, and then once the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn come in, to really shift to that social novel.

They have this sense of being adventuring brothers, but for both of them there is a realization. Once they really understand how the system is weighted against men like them — boys like them — it changes everything, especially for Gig. And for Rye, who is by nature more cautious and less of a leader himself, it changes the way he sees the world, but maybe doesn’t change his actions entirely.

Chapter 16: It is a social novel; it does address those big issues. It has that adventure and Western sensibility all through it, but it’s also a story of brotherhood, of love and sacrifice.

Walter: Gig and Rye feel a sense of responsibility for each other, a sense of love. They also feel burdened by each other sometimes. It’s one of the great joys of writing that you can have a sense of one thing that you’re doing, and then another one emerges. With this book, the surprises were embedded in those characters — in Rye and his view of the world, the idea that he was going to survive this whole thing in a way that other people might not and that he would be indebted to them.

Walter: Gig and Rye feel a sense of responsibility for each other, a sense of love. They also feel burdened by each other sometimes. It’s one of the great joys of writing that you can have a sense of one thing that you’re doing, and then another one emerges. With this book, the surprises were embedded in those characters — in Rye and his view of the world, the idea that he was going to survive this whole thing in a way that other people might not and that he would be indebted to them.

As I said, I thought about writing it like a Western, and one of my early ideas was that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn would be like the Clint Eastwood character, the stranger who rode into town where everything was corrupt, and the hero restores order. And I remember at one point laughing and thinking, “I’m writing a Western, but my Clint Eastwood is a 19-year-old pregnant labor activist.” It filled me with joy, and it made me realize that Rye had a different role than a protagonist typically would. He wasn’t going to be the one doing heroic things (though the way he aids Elizabeth Gurley Flynn turns him into a more active figure), but he is the field upon which this whole thing plays out.

Chapter 16: There was a point at which I had to set this book aside because I was afraid to keep reading. I was so invested in who Rye was, this gentleness of him coupled with a great strength, and I was very nervous. You would have had every right, of course, to take the story in whatever direction you wanted, but I was worried about Rye, and I didn’t want to finish, for fear I would be so hurt.

Walter: One of the aspects of the novel that I realized early on is that I’m writing about 1909, and I’m writing about the city I live in. I’m walking around, and Spokane is still very much a 1909 city. The house I live in, this building was built in 1907. Everything here was built at that time. It was like walking around among ghosts. And in thinking about those characters, many of whom are real, I felt a different kind of responsibility to them than I ever had before. That’s when I realized I would be writing those named chapters in the first person, some of those characters all the way through to their deaths. The intimacy of that made my relationship to the characters a little bit different. You’re with a character and then all of a sudden they’re gone, so I realized that even Rye wasn’t safe.

That was important for me, to put him in a world so treacherous and dangerous that I wasn’t even sure what was going to happen to him until I was about two-thirds of the way into the book. And then I could chart a path through the end, of what would happen to the brothers. Some of the characters, the real historical figures — Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, John Sullivan, James Walsh, Frank Little — their paths were charted. But for the fictional characters, I felt a great responsibility in putting them in real danger but caring for them in a way.

Chapter 16: That is one of your great strengths, the way you infuse each character with such realness, and in some ways, that’s done by differentiating tone, both the words they literally say but also the shape of their moments in a book. In this book, structure plays an important role, too. Those named sections fall between more general sections. How did you come to that structure, and why did this book demand that specific organization?

Walter: I think I’m a structuralist by nature. I’m like those poets who have to write in form, who have to write villanelles or sonnets. There’s a great Charles Baxter essay that I love where he talks about what he calls rhyming action, this idea that action can rhyme the same way words do or the way poems do. And that doesn’t mean that they just repeat; it means rhyme can slant, rhyme can be internal. Those similar kinds of rhyming actions feel true to me, to the way life is lived.

Walter: I think I’m a structuralist by nature. I’m like those poets who have to write in form, who have to write villanelles or sonnets. There’s a great Charles Baxter essay that I love where he talks about what he calls rhyming action, this idea that action can rhyme the same way words do or the way poems do. And that doesn’t mean that they just repeat; it means rhyme can slant, rhyme can be internal. Those similar kinds of rhyming actions feel true to me, to the way life is lived.

As you mentioned, most of the sections would be third person, about Gig and Rye, following them through their lives. But then I had these first-person sections come in, and I kept thinking of the whole novel like the Spokane River. The third-person sections were the main channel, and then I would have these tributaries or streams, or streams of consciousness you could say, undercurrents coming in. I even asked the book designer to come up with something that made me think of an undercurrent, so each chapter has the image, the idea of these things roiling in. Then when we venture out, when we have those tributaries come into the story, just like a stream does, they add to the main channel of the story and become part of it.

The other thing that I really wanted to do was — one of my favorite books is [Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s] One Hundred Years of Solitude, and I’m constantly making tiny homages to the books that have moved me in some way. So starting the book chronologically in 1864 with Plante’s ferry and taking it all the way through to 1964, to the moment when Elizabeth Gurley Flynn dies and Rye is on his deathbed, it was a way to have 100 years of my own city. From before the city existed, when it was just a ferry alongside some Indian villages, to the moment when Rye is in very much the same city that I live in now, a year before I was born, when my dad worked at Kaiser Aluminum, the place where I have Rye work — it was a way to bring the whole thing full circle. I think those kinds of circular structures are really pleasing. They give the work a scaffolding that makes me feel like I can build it.

Chapter 16: As a credit to that, your response could easily lead me to three or four different questions I had prepared because it’s all so tight, the interconnectedness of it all.

Walter: That is what it can feel like, but it isn’t. It’s loose. A novel is the most loose, audacious, terrifying thing you can do. It’s like you’ve opened a window on the universe, and you ask, “How do I order this? What do I do?” I think having that tight structure can help you order the things you’re trying to say.

Chapter 16: And the river as the organizing metaphor is a fascinating idea because the river actually features in a few central spots in the book. As you say, a novel is a terrifying, loose, uncontrollable thing that you have to contain, and so is a river. You show that when Early and Rye and Gig are confronted at the river’s edge by the mob, and Early knocks that cop back, and they escape. Moments later, when Gig is insisting on the IWW code of nonviolence, and Early says, “Nonviolence? When a mob intends to throw you in a river?” and Gig replies, “Especially then.” So the river is threatening, dangerous, a weapon; it is also beautiful and awe-inspiring.

Walter: I’ve always lived on the river, and it is an organizing principle for me, but it’s also where I walk every day to write and think. To have a city with a series of waterfalls at its center — not little falls, but a big, thundering, roaring waterfall — is such a strange, rare thing. I spend a lot of time thinking, what does that mean; how does it manifest itself? So when you can have something that is an organizing principle or metaphor and then have it also be part of the action, it ties those things together.

Walter: I’ve always lived on the river, and it is an organizing principle for me, but it’s also where I walk every day to write and think. To have a city with a series of waterfalls at its center — not little falls, but a big, thundering, roaring waterfall — is such a strange, rare thing. I spend a lot of time thinking, what does that mean; how does it manifest itself? So when you can have something that is an organizing principle or metaphor and then have it also be part of the action, it ties those things together.

When theme and plot and character — when all those things come together, it’s what you’re trying to create anyway, but it just felt right for this story and for the place. I’m writing specifically about my hometown as I did about the village in the Cinque Terre [in Beautiful Ruins] or my version of New York in The Zero. The place has as much to do with what happens as anything.

Chapter 16: And in the section given to The Kid, the river is almost a character itself. Numerous times, the river is literally the subject of the sentence: the river raced; the river was in full churn; still, the river bucked. And then, “I cannot give an account of this river except that it was wide and fast, a torrent out of the mountain lake from which it drained, a blast of angry water over hard rock bed, eager to ocean.” Then we have the action, and the drama of that moment is intense, as The Kid is swept downstream toward the falls, leading to the exchange between Jules and The Kid:

From the back of his pony, the boy raised his hand as I passed, and he called out to me the way you would to a friend you recognized, three short yelps as my barge passed, a song whose meaning I would never know but which I took to mean: I see you.

I can’t help but wonder: In the story of Rye, in the story of Gig and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Ursula the Great, what else did they want but to be seen?

Walter: I think I’ve always been drawn to those kinds of characters. In my short story collection We Live in Water, I set out to write about the people we drive past and don’t see. I live in a city where every street, every school is named for these wealthy men who built the city, and I’m like, they didn’t build the city. Gig and Rye built the city. People whose names we’ll never know. Dozens of human beings are buried inside Grand Coulee Dam because they fell in as they were building it. They’re part of the concrete now. Coming from the working class, from a dad who didn’t graduate high school but was a brilliant man, I definitely feel the responsibility of writing and speaking for those people.

It’s an interesting moment because The Kid breaks the chronology of the novel completely. It’s a kind of fable that exists in Jules’ head that he passes on to Rye, but it’s also that idea of going over — that we all go over alone. I wanted to show The Kid in the moment when he goes over, and he has that realization, that we do — we just want to be seen. We want our basic humanity, which can only be given to us by someone else.

Chapter 16: It’s the individual and the collective, right? We need each other, and we need to have our own unique experiences.

Walter: That’s the difficult thing about writing a novel. A novel is an expression of the individual. And when you set out to write a collective novel — I read a lot of proletariat novels, a lot of big social novels, and it was one of the reasons I wanted to pack this one with the other trappings of a novel — adventure and that sense of the individual — because they can really get lost in a kind of speechifying. Reading Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s speeches, I realized just having someone going around giving early-20th century socialist speeches is a good way to get people to put your book down.

Walter: That’s the difficult thing about writing a novel. A novel is an expression of the individual. And when you set out to write a collective novel — I read a lot of proletariat novels, a lot of big social novels, and it was one of the reasons I wanted to pack this one with the other trappings of a novel — adventure and that sense of the individual — because they can really get lost in a kind of speechifying. Reading Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s speeches, I realized just having someone going around giving early-20th century socialist speeches is a good way to get people to put your book down.

Chapter 16: On that note, let’s talk about a book lots of people put down, one that recurs in your book: War and Peace.

Walter: The depths of that book! The things you can find in it seem endless. It’s interesting because I had previously started it and not finished it, and then I saw a play in New York, Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812. I saw it in a little theater off-Broadway, and they built the whole thing like a 19th century Russian saloon or tavern.

So you walked in, and everyone sat at their tables, and the actors were the waiters, and they brought you a bottle of vodka and some pierogies, and then the play just unfolded around you. It was this central part of War and Peace when Prince Andrey is shot during the battle and thinks he’s dying in the field, and the comet goes over, and that sent me back to the novel. And when I went back to the novel, it felt like a balm in this time when our attention is so split, and when we want things to move more quickly, and that book doesn’t allow you to. You have to live in it.

The way history marches through these characters’ lives reminded me so much of what I was imagining happened in my hometown, where all of a sudden, history lands on this one place. So it became a guiding light. Also, it would have been a book that would have existed for Gig and Rye.

I loved that it was so aspirational, that Gig saw it not just as a story he’d read, but as something that would raise him in class. The most moving scenes in the book take place in libraries because I’ve always seen libraries as the one class escalator we have. Anyone can go into a library. It’s one of the few places where Rye is treated well. The rest of the time, he is looked down upon or not looked at at all, or ignored or chased from town or beaten, but in the library, he gets to be a human being.

Chapter 16: Tolstoy’s book shows the unity of Rye and Gig as they both end up having connections to War and Peace, but it also marks their departure from one another. Gig definitely is a reader. He’s an intellectual; he sees himself as someone who has something to say in the world; and he saw those two volumes of War and Peace that he was able to own as a marker of his becoming. Rye didn’t ever see it that way; in fact, the book was always just a mirror on Gig’s life, until he started reading it. Then, it shows the ways in which story can transform us.

Near the end of the book, when Rye responds to Early’s question “Come on. What stuff are you made of?” by having him read a passage from War and Peace, Early says, “You surprise me, Rye. Every time. You really are the smart one, you know that?” Early is noting not only a change in Rye, but the distinction between the two brothers as well.

Walter: I think Gig has an impatience that all of us could recognize now. If Gig were alive today, he would be tweeting nonstop. Whereas, I think Rye would be soaking up information, and he turns out to be the more contemplative of the two brothers. That impatience is something I’ve self-diagnosed about me but also about the culture around us. It kind of breaks my heart.

Walter: I think Gig has an impatience that all of us could recognize now. If Gig were alive today, he would be tweeting nonstop. Whereas, I think Rye would be soaking up information, and he turns out to be the more contemplative of the two brothers. That impatience is something I’ve self-diagnosed about me but also about the culture around us. It kind of breaks my heart.

And I also appreciate Tolstoy’s commitment to humanity and to history. I was trying to figure out how to balance historical events with fiction, and at certain points in War and Peace, you’re just reading history books or newspapers. I remember reading The Known World by Edward P. Jones, and there’s this moment where the nonfiction comes through and takes you forward in time to names of streets and how this is the world we live in now, and then jerks you back to the fiction. Rather than that being jarring, I found it thrilling. So looking for ways in which to incorporate real events, and in War and Peace that happens throughout.

Chapter 16: Research — discovering the nonfiction that finds a home in your fiction — plays a huge part in who you are as a writer.

Walter: Yeah, that immersion. One of my favorite questions about Beautiful Ruins was when people would ask, “How long did you live in Italy?” and I would say, “Six days!” But I lived there in my mind for a decade. I was constantly reading about it, watching movies, listening to music. That ability to immerse yourself in a place is the obsessive side of fiction writing, and I love that part of it.

Chapter 16: And in this book, you were working with the interplay of the researched history of this place and time and this particular segment of the labor movement, and also drawing upon family history, right?

Walter: I had one grandfather who was an Okie who was displaced during the 30s and lived in workcamps in Colorado and was a hobo, I guess you would call it. He was a homeless itinerant worker. My other grandfather arrived in Spokane for the first time on a train he’d jumped in the Dakotas. For him to tell me those stories — how to find a train, where to pick it up, and where the best hobo camps used to be — it was more the language and romance of it, more than actual family history, that worked its way in. A few bits of family history are there in a kind of suggestive way. Rye leaves Kaiser the same year my father started there. And then, honoring the things they, especially my dad, believed in. He loves Westerns, and he’s spent his life as a Labor Democrat. I wanted to honor the worlds he was in more than recreate them.

Chapter 16: What are you working on now? Is there more Jess Walter to look forward to?

Walter: I’ve got a book of short stories coming out next spring. Most of them have been published elsewhere, all except one called “The Angel of Rome.” The actor Edoardo Ballerini, who did the audio for Beautiful Ruins, and I had been talking about audio stories and how so many readers experience books that way. We realized they aren’t typically written for that purpose, so we decided to kind of write a story together. I wrote it, but Eduardo and I would talk about it, and we did a table reading in New York, where I could hear him, hear the story in his voice, and from that, I did a total rewrite. It’s about to come out on Audible, and then it will be in my collection.

I’m also into another contemporary novel now. When Citizen Vince and The Zero came out within 10 months of each other, it looked like I was just cranking out novels, but the truth was I had been working on both for 10 years! They just happened to finish near the same time. I feel like I am in that position now. I was working on The Cold Millions while I was working on this other contemporary novel, which is comic and suspenseful and kind of sexy, I hope.

Sara Beth West is a writer and reviewer, usually found at sarabethwest.com. She lives in Chattanooga with her family, dogs, and a cat who always, always, always thinks it is time for dinner.