Out of the Mouth of Hell

Peter Carlson recounts a Civil War drama of capture, imprisonment, and escape

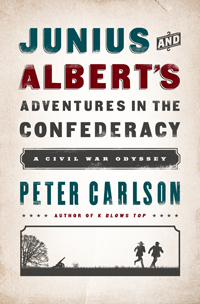

First things first. Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey is not a sci-fi, time-travel buddy film. It is Peter Carlson’s telling of a true story, a gloriously entertaining book that should be on the reading list of anyone curious about the underbelly of the Civil War. In its simplest sense, this tale, so little known that even most Civil War mavens will not have heard it, is about how men trapped in a horrific conflagration survived using their wits and determination. In a broader sense, Carlson’s description of the adventures of two captured Yankee reporters encompasses all that is noble and ignoble about war. And it does so, most remarkably, with almost no discussions of battles or generals.

Junius Browne and Albert Richardson were reporters for the New York Tribune. They worked for famed newspaperman and abolitionist Horace Greeley, a source of personal pride for both men that would prove a heavy burden. Browne and Richardson shared their boss’s hatred of slavery. This hatred was well documented in the pages of the Tribune, and made that most Yankee of newspapers the object of contempt throughout the South. In today’s world of Fox News v. MSNBC, it is important to remember that in days past reporters were expected to be advocates for their employers’ political positions, facts be damned. Indeed, “facts” were often not just ignored but fabricated, even by the heroes of this tale. As Carlson notes in describing a particularly fanciful piece of wartime reporting by Junius Browne, “Newspapers routinely enlivened their meager supply of facts by garnishing them with rumors, exaggerations, political rants, vicious invective, and the kind of pseudo-poetic prose that escaped the gravitational pull of truth and soared into fantasy.” This kind of sensationalism, mixed with the deadly politics of the day, could earn a reporter more than a charge of bias—it could get him killed.

Junius Browne and Albert Richardson were reporters for the New York Tribune. They worked for famed newspaperman and abolitionist Horace Greeley, a source of personal pride for both men that would prove a heavy burden. Browne and Richardson shared their boss’s hatred of slavery. This hatred was well documented in the pages of the Tribune, and made that most Yankee of newspapers the object of contempt throughout the South. In today’s world of Fox News v. MSNBC, it is important to remember that in days past reporters were expected to be advocates for their employers’ political positions, facts be damned. Indeed, “facts” were often not just ignored but fabricated, even by the heroes of this tale. As Carlson notes in describing a particularly fanciful piece of wartime reporting by Junius Browne, “Newspapers routinely enlivened their meager supply of facts by garnishing them with rumors, exaggerations, political rants, vicious invective, and the kind of pseudo-poetic prose that escaped the gravitational pull of truth and soared into fantasy.” This kind of sensationalism, mixed with the deadly politics of the day, could earn a reporter more than a charge of bias—it could get him killed.

Despite the hazards, both Browne and Richardson volunteered to report from the South, where they were traveling with General Grant’s forces. On May 3, 1863, they hitched a ride on a Union tugboat trying to run the gauntlet of Confederate artillery guarding the Mississippi River at Vicksburg. The reporters were hoping to get in position to observe Grant’s assault on the last rebel-held city on the river. They didn’t make it. Captured when the tug was destroyed by cannon fire, the two men were faced with a dilemma. “Should they,” writes Carlson, “admit that they were Tribune reporters or should they pretend to work for a less loathed journal?” They chose the honorable truth, figuring they’d be found out soon enough anyway. Perhaps they should have tried the lie.

Civil War prisons were horrible places. Full of disease and run by men who were at best unable to help and at worst sadistic, both Northern and Southern prison camps were often nothing less than death traps, hellholes of suffering. Late in the war conditions were so bad that Union soldiers sometimes volunteered to join the Confederate army just to get enough food to survive. It was into this Hades that Browne and Richardson were transported, first to Libby and Castle Thunder prisons in Richmond, then to the notorious Salisbury Prison north of Charlotte, North Carolina. As civilians and educated men, they often received better treatment than military officers or the lowly enlisted men, but they still suffered. And no Confederate officials were willing to go out of their way to assist in the release of men who were friends and colleagues of Horace Greeley. So they languished in captivity. As conditions worsened toward the end of 1864 and death cut swaths through the prisoners, Browne and Richardson decided that escape would be their only salvation.

Civil War prisons were horrible places. Full of disease and run by men who were at best unable to help and at worst sadistic, both Northern and Southern prison camps were often nothing less than death traps, hellholes of suffering. Late in the war conditions were so bad that Union soldiers sometimes volunteered to join the Confederate army just to get enough food to survive. It was into this Hades that Browne and Richardson were transported, first to Libby and Castle Thunder prisons in Richmond, then to the notorious Salisbury Prison north of Charlotte, North Carolina. As civilians and educated men, they often received better treatment than military officers or the lowly enlisted men, but they still suffered. And no Confederate officials were willing to go out of their way to assist in the release of men who were friends and colleagues of Horace Greeley. So they languished in captivity. As conditions worsened toward the end of 1864 and death cut swaths through the prisoners, Browne and Richardson decided that escape would be their only salvation.

In the last act of this drama, the escape from Salisbury and the desperate journey toward the Union lines, Carlson reveals a world far removed from the brutal yet usually clear-cut conventional war of Blue v. Gray. To get away from Salisbury and across the Piedmont, Browne and Richardson had to find Union sympathizers in the heart of the Confederacy. Slaves and former slaves were their most reliable helpmates, an irony not lost on the abolitionists. “[T]he slaves had never let them down, feeding and sheltering the strangers and leading them to safety, risking a beating—or worse—if they were caught. It was, [they] realized, the story of the Underground Railroad with the colors reversed… .” Then came the mountains. The Appalachians of the Carolinas and Tennessee were hotbeds of guerilla warfare, where friend and foe dressed alike and strangers could disappear if they revealed their political persuasion to the wrong person. Negotiating this physical and political bramble was an odyssey worthy of Greek heroes and included encounters with a secret society, an Old Testament-style warrior, and an ethereal beauty who appeared and disappeared from the forest like a phantom.

Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy is the perfect antidote to the endless stream of Civil-War-sesquicentennial, scholarly tomes about this or that battle or major general. It is a grand tale of adventure, full of heroes and villains and a window into a world of honor and hypocrisy long dead yet still oddly relevant.