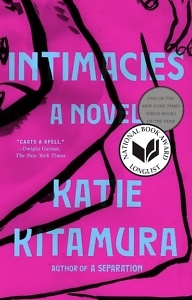

Outwardly Fine, Inwardly Lost

Katie Kitamura’s international novel hits close to home

From the outside, the unnamed protagonist of Katie Kitamura’s fourth novel, Intimacies, is an elite woman who is excellent at her job as an interpreter for the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

She is fluent in English and Japanese through her parents, learned French through a childhood in Paris, and is competent in Spanish and German from her years living in other European cities. As an interpreter, she makes full use of her multilingual abilities. The job also requires precision, speed, and most importantly, the kind of poised, thick-skinned personality that allows her to listen and reiterate stilted legalese and horrifying testimonies on a day-to-day basis.

Kitamura’s narrator is what some of us would call a third culture kid (TCK), someone who grew up in a culture different from their parents’. My resume is hardly as impressive as this character’s, but I identify as a TCK, having spent much of my life going back and forth between Japan and various parts of the U.S. For this reason, reading Intimacies felt strikingly resonant. The narrator says she moved around so much that “there was no place I would think of as my childhood home.” In The Hague, she notes, “A place has a curious quality when you have only a partial understanding of its language.” While interpreting, she muses that “[l]anguage loses its meaning.”

Kitamura’s writing is impeccable, which is both a compliment and an observation about the choice she made for the voice of this particular narrator, whose work is all about the accuracy of words.

To truly understand the artistry of this novel, however, it isn’t enough to appreciate what’s on the page. Everything the narrator omits is just as important. The dark matter of this novel, if you will, sheds more light on what’s really happening inside this polished character’s head.

In the opening paragraphs, the narrator summarizes her situation concisely, perhaps to a fault: She chose to accept a one-year contract to work at The Hague because she was eager to get out of New York, a place she associates with the recent passing of her father. After his death, her mother quickly moved to Singapore. These details are mentioned matter-of-factly and not reiterated again for a long time, which signaled to me that the underlying current of this book is grief — not only for her father, but for the proximity to her mother, and most of all, for the hope of ever having a place she could call home.

In the opening paragraphs, the narrator summarizes her situation concisely, perhaps to a fault: She chose to accept a one-year contract to work at The Hague because she was eager to get out of New York, a place she associates with the recent passing of her father. After his death, her mother quickly moved to Singapore. These details are mentioned matter-of-factly and not reiterated again for a long time, which signaled to me that the underlying current of this book is grief — not only for her father, but for the proximity to her mother, and most of all, for the hope of ever having a place she could call home.

This kind of grief for something that never existed to begin with is so difficult to articulate, yet Intimacies gets close to it, or at least inside the head of someone struggling to come to terms with it. After a particularly grueling day at the ICC, the narrator notes, “It is surprisingly easy to forget what you have witnessed, the horrifying image or the voice speaking the unspeakable, in order to exist in the world we must and we do forget, we live in a state of I know but I do not know.” This could just as well be a statement about witnessing her father’s death in New York, though I’m sure the narrator would be quick to deny it.

It is no wonder that, under her circumstances, the narrator might constantly be second-guessing the words and body language of Jana, a friend of a friend who also feels like an outsider in The Hague as a Black woman from London. When the narrator embarks on a romantic relationship with a Dutch man named Adriaan, she realizes that he, too, is impossible to interpret. She wants to understand, and she says she understands — but that doesn’t mean she does.

I read the book when it came out in the summer of 2021, and my initial enjoyment of it was tied to the feeling of escapism. I have never been to the Netherlands, and since international travel was still risky for our family, the book felt like an opportunity for my mind, at least, to wander outside of our isolation in Nashville.

Rereading it now, about a year later, Intimacies left me with a different interpretation. As the world seems to be hurrying itself back to crowded events to make up for all that lost time, I can’t help but feel like we are meant to interact with each other with a tacit agreement to pretend the last two and a half years didn’t happen. As though many of us didn’t experience life-shattering grief for a person, or perhaps a thing that cannot be named.

We seem to be past the stage of genuine concern when we ask each other, “How are you?” We are back to treating that phrase like a mere formality. Intimacy — to borrow from Kitamura’s title, a word that is reiterated and analyzed throughout the book — is elusive to me in this current world. There must be others who also feel as perplexed about how to navigate this new yet sort of old world, who feel alone in not knowing how to process it all. Kitamura’s novel might not provide answers, but it will offer kinship and acknowledgement. In that way, Intimacies might be timelier than ever.

Yurina Yoshikawa holds an M.F.A. from Columbia University and teaches fiction and nonfiction writing at The Porch. Originally from Tokyo, she spent 10 years in New York before moving to Nashville in 2017. Her writing has appeared in The Japan Times, The Pinch, The Tennessean, and elsewhere. She was the winner of the 2020 Tennessee True Stories Contest and a 2021 recipient of the Tennessee Arts Commission Individual Artist Fellowship. She currently lives in Inglewood with her husband and two sons