Pack Man

Michael Nelson analyzes FDR’s ill-fated court-packing plan of 1937

In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed legislation that allowed him to appoint one justice to the Supreme Court for every sitting judge over age 70. This “court-packing” plan met stiff opposition. Senator Burton Wheeler objected that, if the law was enacted, the Constitution would become “as ductile as a gob of chewing gum.” In a short and sharp analysis titled Vaulting Ambition, Michael Nelson analyzes this moment of presidential overreach, focusing on Roosevelt’s key decisions along the way.

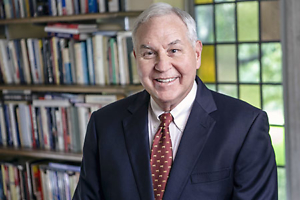

Michael Nelson is the Fulmer Professor of Political Science at Rhodes College, a Senior Fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, and for 30 years the political analyst for Action News 5 in Memphis. He is the author of many books and articles on the American presidency, elections, public policy, and Southern politics. His most recent books include Resilient America, an account of the 1968 presidential election that won the Richard E. Neustadt Award for the Outstanding Book on the Presidency and Executive Politics.

Michael Nelson is the Fulmer Professor of Political Science at Rhodes College, a Senior Fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, and for 30 years the political analyst for Action News 5 in Memphis. He is the author of many books and articles on the American presidency, elections, public policy, and Southern politics. His most recent books include Resilient America, an account of the 1968 presidential election that won the Richard E. Neustadt Award for the Outstanding Book on the Presidency and Executive Politics.

Nelson answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: What were President Roosevelt’s motivations for proposing the “court-packing” plan? How did he envision the role of the Supreme Court?

Michael Nelson: Roosevelt wanted to embed the New Deal in the permanent structure of American government. During his first term, the Supreme Court posed an obstacle to his success, overturning more of his policies than any other president’s before or since. In his view, the court’s job was to be part of a “three-horse team” along with the president and Congress, adapting its interpretation of the Constitution to the changing times that he represented. None of the justices retired during his first term, and he was convinced that the “nine old men” on the court would hang on as long as they lived.

Chapter 16: Why is it even possible to change the number of justices on the Supreme Court? Why, since 1869, have we been stuck on nine?

Nelson: The Constitution is silent on the number of justices on the court, leaving it to Congress to make that call. From 1789, when the Constitution took effect, until 1869, the size of the court grew as the country grew, rising over time from five justices to nine. By 1937, when FDR introduced his bill to expand the court, it had been the same size for two-thirds of a century, and most Americans assumed that nine was the only possible number.

Chapter 16: The central thread in Vaulting Ambition concerns FDR’s key decisions about conceiving and presenting his plan for the court. What were his fateful choices? Was his decision-making process flawed?

Nelson: During his campaign to tame the court, FDR made a series of fateful decisions. Two stand out. One was not to seek a constitutional amendment to change the Constitution rather than a bill to change the court. The other was not to compromise on his demand that Congress dramatically increase the number of justices from 9 to as many as 15.

Nelson: During his campaign to tame the court, FDR made a series of fateful decisions. Two stand out. One was not to seek a constitutional amendment to change the Constitution rather than a bill to change the court. The other was not to compromise on his demand that Congress dramatically increase the number of justices from 9 to as many as 15.

Chapter 16: Roosevelt won reelection in 1936 in a landslide. Yet in terms of his Supreme Court plan, was it a missed opportunity?

Nelson: Remarkably, FDR said nothing about the court during his 1936 reelection campaign, which meant he could not reasonably claim a mandate for the court-packing bill he introduced as soon as his second term began.

One other aspect of the 1936 election is important. Justice Owen Roberts had hoped to be the Republican nominee for president, as Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes had been in 1916. When Roberts realized that wasn’t going to happen, he stopped voting to overturn Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation and started voting to uphold it.

Chapter 16: “We lost the battle,” Roosevelt stated in the aftermath, “but we won the war.” How might New Deal liberals see the court-packing story as a success? Are they right?

Nelson: It’s true that the court changed course, but for a couple reasons that FDR could not really take credit for. One was that Congress, while rejecting the court-packing bill, passed another law allowing full pensions for justices who retired, which a couple of them then did. The other was that some of the older justices died. Through deaths and resignations, Roosevelt eventually was able to appoint an almost entirely new court without any change in its size.

Chapter 16: In 2021, President Biden seemed to flirt with a redux of the court-packing plan, as a response to the far-right majority in the current Supreme Court. Based on your understanding of Roosevelt’s ordeal, how would you advise Biden?

Nelson: Now that the size of the court has been nine not for two-thirds of a century but for a century-and a half, Americans are even more inclined to think that the number is sacred. Biden wisely decided not to try to pack it. My only advice would be to stick to that decision.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.