Perilous Waters

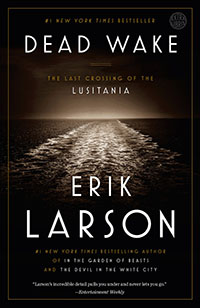

Nonfiction master Erik Larson takes readers aboard the final voyage of the Lusitania

Erik Larson’s seventh book, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, now out in paper, follows the crew and passengers of the doomed ship, along with their German pursuers aboard the submarine U-20, toward their fateful meeting on May 7, 1915. As with his previous bestselling historical works such as Isaac’s Storm, The Devil in the White City, and In the Garden of Beasts, Larson organizes carefully researched facts around the characters at the heart of the story with all the skill of a suspense novelist. In Dead Wake, readers are privy to the thoughts of Winston Churchill, the plans of the U-boat captain, Walther Schwieger, and many of the passengers and crew aboard the great British liner.

Erik Larson recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Erik Larson recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: You write in a note to readers that you thought you knew all about the Lusitania, “but, as so often happens when I do deep research on a subject, I quickly realized how wrong I was.” Can you describe the “deep research” process, and some of the surprising facts it revealed?

Larson: Well in this case it didn’t even take terribly deep research to realize there was more to the story of the Lusitania than I learned in high school. I think what most of us were taught, or at least absorbed, was that the Lusitania episode was the World War I equivalent of Pearl Harbor. It wasn’t. I was surprised right off the mark by the fact that America didn’t enter the war for two full years after the sinking, and that when President Wilson finally asked for a declaration that a state of war existed between America and Germany, he never once mentioned the Lusitania. But it was the powerful details of the sinking—lifeboats falling on top of lifeboats, people getting sucked into the ship’s funnels, the U-boat commander’s War Log—that really startled me and persuaded me that I could bring something new to the historiography of the event.

Chapter 16: What it was it like crossing the Atlantic on the Queen Mary 2? How did the experience inform your book?

Larson: It was, in fact, very valuable, because finding oneself in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean is a singular sensation, one you cannot possibly grasp until you are actually there. You are very much aware of how alone your ship is, and how, if anything awful happened, help would not be likely to arrive for a very long time. Equally important, though, was what my two voyages taught me about the pace and quality of shipboard life. There simply is not much to do, except read, eat, and drink, and occasionally hear a lecture or perhaps watch a movie, or participate in a talent show. There is time to be filled. It is somehow very important to know that, and to understand that the passengers on the Lusitania had spent a long, languid week at sea that lulled them into a sense of safety … and then!

Chapter 16: Although virtually all readers know the gist of what will happen before they even open the book, you create a great deal of suspense through the actions of many individual characters. Is there a special trick to building and maintaining suspense within a lengthy historical work?

Chapter 16: Although virtually all readers know the gist of what will happen before they even open the book, you create a great deal of suspense through the actions of many individual characters. Is there a special trick to building and maintaining suspense within a lengthy historical work?

Larson: That’s the beautiful paradox of reading: If you tell a story properly, readers will suspend their knowledge of an event and find themselves hoping that this time the outcome will be different. I don’t think there is any great trick here. If people care about characters, they’ll care about what happens to them. If anything, knowing that the ship will get torpedoed makes the whole task of telling the story in a suspenseful way much, much easier. The fact I was able to reconstruct the submarine’s journey, thanks to the captain’s War Log, further enhanced the whole effect, because if you know the U-boat and the Lusitania are on a collision course, just cutting from one to the other over that preceding week is very effective.

Chapter 16: In your acknowledgements, you mention that when writing about the Lusitania, “one has to be careful to sift and weigh the things that have already been published on the subject. There are falsehoods and false facts, and these, once dropped into the scholarly stream, appear over and over again.” If it’s not too undiplomatic toward other historians, would you point out an example or two of these historical errors?

Larson: I don’t particularly want to name names, but there was one book that, among Lusitania experts, is considered to have played rather fast and loose with the facts, including touching up, or even making up, quotes that no one actually said. And some of these quotes have made their way into subsequent books, providing the imprimatur of fact. Happily I had a wise source who guided past those particular pitfalls.

Chapter 16: You write of large and small acts of bravery among the survivors of the sinking. Which struck you the most?

Larson: I think, frankly, the bravest thing was simply to stand at the rail of that ship, as much as sixty feet above the surface of the sea, and just jump—something many men, women, and children did, with or without life jackets. How terrifying that must have been, and yet they did it anyway, and that’s the true definition of bravery.

Chapter 16: There seem to be a number of writers today who, like you, seek to employ all the narrative and emotional force of fiction in writing about history. Who are your own favorites?

Larson: There a lot of writers trying their hand at this genre, and not always with the respect necessary for the line between fiction and nonfiction. The best of course is David McCullough, who wrote one of my all-time favorite nonfiction works, Mornings on Horseback, about the young Teddy Roosevelt and how he went from being an asthmatic kid to the rough-and-ready character he became.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a new textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.